Advertisement

Straddling Innovation And Tradition, Boston Lyric Opera Celebrates A Birthday And Seeks A Home

Some performing arts organizations make their names by irreverently shaking up the established order. Others thrive by providing that order in the first place. But to be an innovator and an institution — that’s a hard note to hit. Yet it seems to be the space Boston Lyric Opera aims to occupy.

As it opens its 40th season with a controversial staging of one of opera’s greatest hits, the BLO steps with firm footing onto uncertain ground. With a $9.6 million operating budget this year, 28 full-time employees and plans to hire more than 500 people over the course of the 2016-'17 season, the BLO is easily Boston’s biggest opera company — yet it has a cloud of uncertainty hovering over at least one key aspect of its identity. As it continues to grow into its role as the city’s elder statesman among opera producers, the BLO still seeks to definitively assert its artistic identity, and to find a permanent home.

BLO leader Esther Nelson (as artistic and general director, she steers both the business and artistic ends of the organization) announced last October that the company would leave the Shubert Theatre, its principal venue since moving from what is now known as the Cutler Majestic Theatre in 1998. Though it has entered the running to use the Colonial Theatre once that historic theater’s owner, Emerson College, decides what it wants to do with it, BLO will spend its 40th season as a fully itinerant company, producing four shows in four different venues.

That first show is likely to be a doozy.

The material, Bizet’s “Carmen,” is very familiar. It was the first show programmed by Nelson for the BLO, opening the 2009-'10 season. More notably, it was the foundation for perhaps the company’s greatest triumph to date, two performances on Boston Common in 2002 that reportedly drew well over a combined 100,000 attendees.

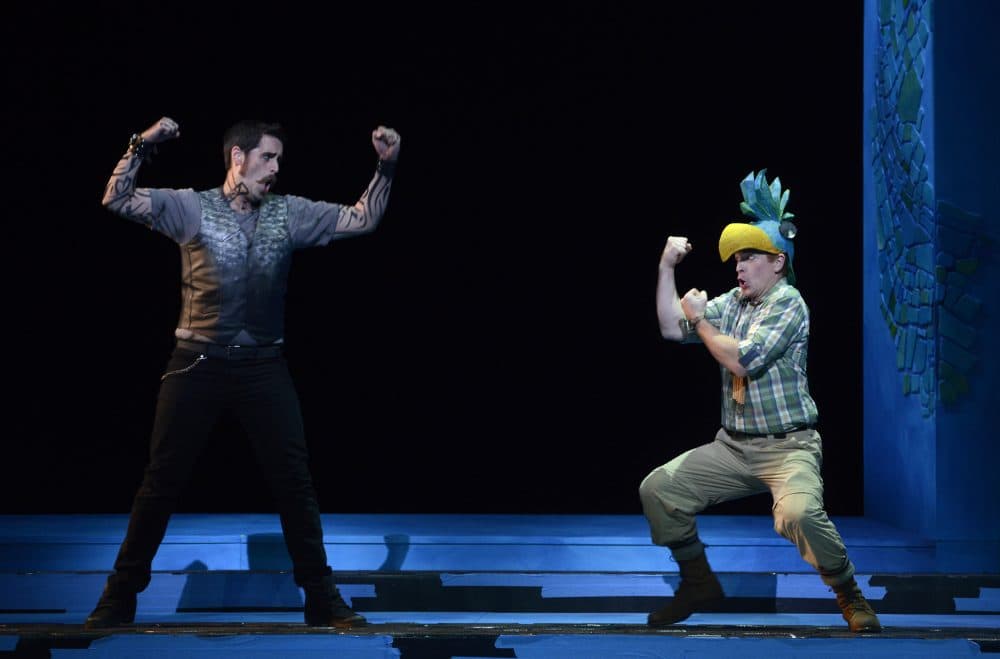

This particular staging, though, is a different story. A co-production with San Francisco Opera, it marks the first United States production by controversial director Calixto Bieito — sort of. It’s a revival of Bieito’s staging, first seen in Catalonia in 1999, helmed by revival director Joan Anton Rechi. San Francisco Opera built the sets and costumes and mounted the show this summer to mixed reviews, with a different cast. (Bieito will land in the States with force with a new staging of Verdi’s “La Forza del Destino” at the Metropolitan Opera next season, to be conducted by James Levine.)

It’s a bold choice for a legacy company celebrating an auspicious anniversary. Bieito’s brash interpretations have thrilled European audiences for decades, though this “Carmen” — complete with nudity and simulated sex acts -- scandalized British operagoers a few years ago.

“It’s not exactly shocking, but it’s certainly stimulating and provocative and I find it very exciting,” says conductor David Angus, who was brought in by Nelson to be the BLO’s music director in 2010. “I think it fits for us in that we are just trying to look at everything afresh. We don’t throw away tradition, we examine tradition and we keep what we like. What we don’t want to do is become a museum of old styles.”

Nelson says this “Carmen,” which performs at Boston Opera House through Oct. 2, features the largest group of performers in the BLO’s history, with 54 singers in the chorus and more than 60 musicians in the orchestra. These artists, for the most part, are locals; the 12 soloists are not.

Advertisement

“In addition to an international cast and international stage director and an international production, what makes it really come to life in the end — the bigness — is local talent that we take the opportunity to showcase,” Nelson says.

Of Bieito, Michael White once wrote in The New York Times that his productions “come soaked in blood, gore and urine, and [are] enlivened by relentless scenes of anal rape, fellatio, masturbation and drug-crazed couplings.” Yet, while Nelson’s tenure has featured plenty of provocative artistic choices — like a staging of Philip Glass’ “In The Penal Colony” with strong allusions to Edward Snowden — the Boston Lyric Opera has not always thrived on the cutting edge. It was long considered the more staid opera company among its scrappy competitors.

During much of the BLO’s history, now-defunct companies like Sarah Caldwell’s Opera Company of Boston and Opera Boston (formerly Boston Academy of Music) have more frequently been cited as purveyors of the most exciting opera locally. In a comprehensive history of the BLO by Jane Pisciottoli Papa recently posted on its website, the 16-year tenure of general manager Janice Mancini Del Sesto, Nelson’s processor, is described as encompassing “the evolution of BLO from a moderately respectable regional company to one that had begun to merit national attention.”

Poet and author Lloyd Schwartz, a contributor to The ARTery and longtime observer of the city’s music scene, credits Nelson for keeping the organization afloat in challenging times, but is decidedly unimpressed by its artistic output.

“It seems to me that what the Boston Lyric Opera has substituted for conservative productions are the clichés of avant-garde productions, but not the real spirit of the avant-garde,” he says. “If you’re going to do something kind of avant-garde and unusual, I want you to do it with imagination and insight and originality.”

BLO’s forward-looking slant has been noticed, though. In a favorable 2011 review of Viktor Ullmann’s little-performed “Emperor of Atlantis, or Death Quits,” Allan Kozinn wrote in The New York Times that the company “presents only a handful of productions a year but clearly intends them to catch the interest of operagoers around the country.”

Its “Opera Annex” series of operas staged in unconventional locations has garnered much attention — and has been most likely to lure those New York critics. A 2014 production of Frank Martin’s “The Love Potion” was staged at Temple Ohabei Shalom in Brookline (and described in The New York Times as “enthralling [and] poignant”). Schwartz describes a 2012 production of Peter Maxwell Davies’ “The Lighthouse” at the JFK Library in Dorchester as “a brilliantly imaginative use of a really unorthodox space. It was fantastic. Thrilling.”

Here's a time-lapse video depicting the BLO's transformation of the Cyclorama in the South End into a venue for "In The Penal Colony."

These successes (both artistically and on the publicity front) with productions in one-off locations are perhaps a good sign with respect to the company’s current, itinerant status.

Along with a consortium of other Boston arts presenters, BLO has submitted a proposal to Emerson for use of the Colonial. It has also submitted a separate proposal covering only its own, individual use of the venue. Whether as sole resident company or partner in a time-share, the BLO’s first preference may or may not be the Colonial. Though a gorgeous and historic house, with more advantages for large productions than the Majestic or the Shubert, it’s still not ideal for opera. Angus says its lack of a standard orchestra pit means “a lot of investment” would still be needed to make it suitable. (For a BLO production of “La Bohème,” the company rehearsed its chorus at the Colonial but had nowhere to put the orchestra, he says.) And if the Colonial is again run by a commercial operator on Emerson's behalf, rehearsal and performance time in the venue is likely to remain expensive.

The underlying problem is that Boston lacks a purpose-built home for opera. Classical music critic Jeremy Eichler wrote in The Boston Globe that this lack of a true opera hall should be considered a “simple matter of civic self-respect for a city that likes to feel proud of its performing arts scene.” The city once had such a venue, but the Boston Opera House was torn down in 1958, its existence now hinted at by the side street off Huntington Avenue where it was located — Opera Place.

But when all is said and sung, is Boston a good place for opera? Nelson says an affirmative answer is found in the city’s wealth of talent, from musicians to experienced production staff.

It’s not by accident that Boston Lyric Opera has survived where so many of its organizational peers have faltered. It’s earned its place as the city’s chief producer of opera. But as it enters its fifth decade, the BLO's defining statements may yet be still to come.

Until it finds a permanent home, it may have trouble developing that much-sought "relationship" with its audience that arts organizations endeavor to foster in this age of declining subscriptions, instant feedback and the expectation of value-added goodies like free lectures and other associated programming.

"You form a relationship with a company and you have an expectation," Nelson says of audience members. "It's like when you visit family — you go home and spend a week with them and you have a different expectation then when you have dinner with someone you hardly know."

For now, the BLO and its fans will be dining together (so to speak) in a series of different rooms. The manner in which they finally find themselves together at home again may say much about the future direction of Boston's opera scene.