Advertisement

What Bob Dylan Learned In Harvard Square

For Christopher Ricks and other professorial types around Boston, Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize may help validate their interest in the singer as a literary figure. But in addition to celebrating Dylan’s impact inside the academy, we should also celebrate the legacy he left behind in the city of Cambridge itself.

Accounts of Dylan’s early life tend to jump from his unassuming childhood in Minnesota to when he burst on the scene in New York. But before Dylan had really arrived in Greenwich Village, he had made a critical detour into Harvard Square in the early '60s, where the folk revival had already begun to blossom.

To piece together the story of Dylan’s time here, I spoke with two members of the non-profit archival group, FOLK New England: Betsy Siggins and Mitch Greenhill. Both Siggins and Greenhill were intimately involved with the Cambridge folk scene: Siggins was a founding member of the city’s most vital folk venue and Greenhill — son of Manny Greenhill, who managed many of the most prominent local artists — was also a noted folk performer and recording artist in his own right. (Greenhill is now also the president of the roots music book agency FLi Artists). Their stories, along with Eric von Schmidt’s now out-of-print "Baby Let Me Follow You Down: The Illustrated Story of the Cambridge Folk Years" and David Hajdu’s 2001 book "Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña," help make the case for why any narrative of Dylan’s life shouldn’t overlook the Cambridge connection.

How Cambridge Shaped The Nobel Laureate

The scene in Cambridge at the beginning of Dylan’s career was centered around a small, unassuming room on Mount Auburn Street known as the Club 47. The area around the club, which was just blocks away from Harvard Yard, “was considered the hinterlands,” according to the club’s co-founder, Joyce Chopra, “You were slumming it if you went down there,” she admits in "For The Love of the Music," a 2012 documentary on the history of the club.

Chopra, born as Joyce Kalina, had started the club with fellow Brandeis grad Paula Kelley in 1958. But it wasn’t until an unassuming, barefoot Boston University dropout named Joan Baez showed up to sing on Mount Auburn Street that the club started taking folk music seriously.

Even in her earliest performances, Baez, who was still a teenager at the time, managed to consistently pack the house at Club 47. She stole the show night after night, with a voice that drowned out anyone who tried to sing with her. She knew that she was a star, even if she was also still a self-conscious teen. She's quoted as saying:

"I knew I could do what the other folk singers were doing and a lot better than them. In my mind I was still the girl kids used to taunt and call a dirty Mexican, but I could sing. I realized that was something I could do to prove that I was valid, and I liked it a lot more than going to class."

Dylan might have reached the same conclusion about what he liked, but he didn’t have quite the same results. He’d gotten into folk music a couple years after Baez, and when he first came down to gig at the Club 47 in 1961, he was turned down on the spot.

Club owner Paula Kelley later described Dylan at the time “as a really scrawny, shabby kid … the only person I’ve ever seen with green teeth. Singing in-between sets for nothing than going out and saying he’d sang at the Club 47.”

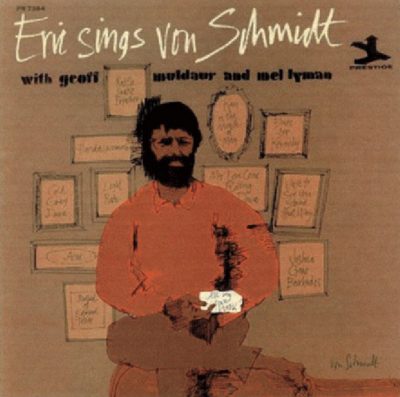

Yet even if Dylan wasn’t able to get regular gigs, he was a determined networker. While in Cambridge, he managed to connect with a local legend: blues guitar player and illustrator Eric von Schmidt.

Schmidt, who was just a few years older than most of the local performers, was considered the “grandfather of the Cambridge folk scene,” the Harvard Square counter-part to the Village’s Dave Van Ronk, according to Siggins. Schmidt was among the most accomplished musicians on the scene, a dedicated student of the Leadbelly songbook who managed to remake the country blues in his own style. He was also life of the party: He had an open door policy at his place outside Harvard Square where musicians could crash after shows and stay up all night drinking.

When Schmidt met the new kid from Minnesota, still in his “Huck Finn hat” phase, he invited him to come play croquet. As Schmidt writes in his history of the Cambridge folk scene,“Dylan was absolutely worst player I’d ever seen … a little spastic gnome.”

Eventually, Schmidt and Dylan started gathering a group for a party. They played harmonica duets together to rouse the crowd. But when Schmidt brought out his guitar, Dylan didn’t join in; he just listened.

Advertisement

“It was something the way he was soaking up material in those days — like a sponge and a half,” Schmidt writes.

Siggins says Schmidt helped Dylan expand his repertoire and to “sop up all kinds of influences” outside of his Woody Guthrie routine.

“Eric was a blues musician, with an enormous amount of authenticity. He wasn’t just this white guy interpreting the blues; he was making it available to the next generation.”

One of the songs Dylan listened to Schmidt play the day they met to play croquet was “Baby Let Me Lay It On You,” a song he’d adapted from a Blind Boy Fuller record. That song later appeared, in a radically altered form, as “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down,” the standout track on Dylan’s self-titled debut album.

“I first heard this from Ric von Schmidt,” Dylan says plainly on the spoken intro to the record. “He lives in Cambridge. Ric’s a blues guitar player … I met him one day in the … green pastures of Harvard University.”

Mitch Greenhill thinks Dylan actually “copped his version of the song from Dave Van Ronk,” who was playing his own arrangement of the song at the time, but Dylan was then feuding with his New York mentor over their competing renditions of “House of the Rising Sun.” The shoutout to Schmidt may have been more political than sincere, but it’s still notable as one of Dylan’s only recorded references to his time in Harvard Square.

Dylan’s connection with Schmidt wasn’t just musical, Siggins says. "Eric had a huge personality and they got along well. It was just serendipitous that they met each other."

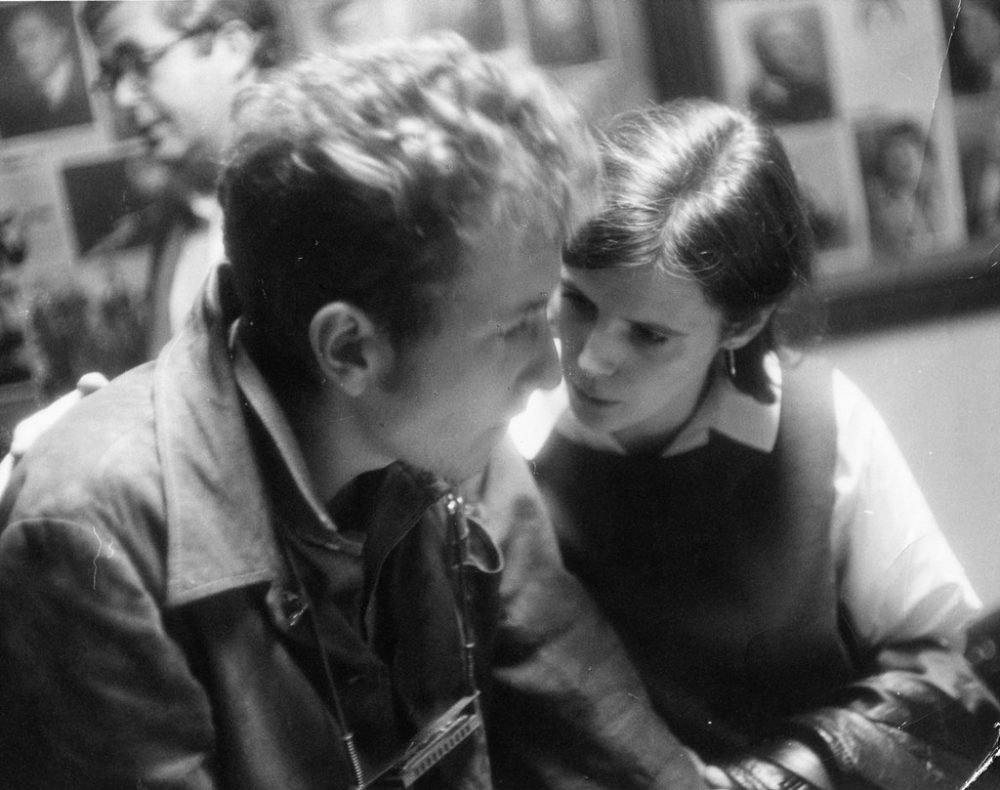

You can hear the odd chemistry between the two of them in an early recording of a shambolic live performance at the Club 47 included in "For the Love of Music" documentary.

Schmidt’s intro to the performance hints at the fact that he knew very little about the man sitting in with him on stage:

Schmidt: “Here’s a fellow from down south, New York there.”

Dylan: “I’m not from New York.”

Schmidt: [Laughs.] "He’s not from New York he says. I don’t know where he’s from, someplace out there in the Midwest…"

Dylan: "Boston."

Schmidt: "Out in the midwest of Boston. West Roxbury…"

The performance that follows is a chaotic, out-of-tune mess, as well a complete joy.

“It was learn as you play,” Siggins says of the recording, “that concert we have is a real gem. It was completely unrehearsed, they’d probably been drinking a small amount of rum that day. It was back when everyone was loosey goosey.”

Getting Down To Business

Schmidt wasn’t the only person Dylan met in Cambridge. David Hajdu’s book details a relationship with the Cuban-Irish-American folk singer Richard Fariña, who had also made it as a published poet and short story writer (and who would later marry Joan Baez’s younger sister, Mimi).

In August 1961, Schmidt invited Dylan, along with Fariña’s then-wife, the Texan folk singer Carolyn Hester, to come out to Revere Beach, which at the time was more of a run-down bohemian hang out than a real beachfront. Hester noted how out-of-place Dylan seemed out on the beach in daylight. “He looked so pale, almost translucent” Hester said, while Schmidt described him as looking “emaciated with his shirt off.”

But the key to the Revere Beach trip may have been an off-hand comment from Fariña:

"We should start a whole new genre. Poetry set to music, but not chamber music or beatnik jazz, man. Music with a beat. Poetry you can dance to. Boogie poetry!"

Schmidt says the comment, coming from a real published poet, stunned Dylan.

"Like how’s he going to do that on the dulcimer, the f---ing dulcimer? But he had something. For all I know, Dylan had the same idea. A million people might have had the same idea … but nobody else I knew was talking that way."

Whatever the source of inspiration was, Mitch Greenhill noticed Dylan began to change rapidly after his first appearances on the scene. He would later see him perform new songs for impromptu crowds on the banks of the Charles River.

“When I first saw him, I thought he was imitating Ramblin’ Jack Elliott imitating Woody Guthrie. A few months later, I thought he was just imitating Woody. A few months later, he wasn’t imitating anyone.”

Another part of Dylan’s rise was more practical. His initial connection with Hester in Cambridge led to an invitation to record harmonica for her on her third album for Columbia Records. The connection at Columbia also led him to sign with Al Grossman, the manager for some of the biggest names in the folk business.

Grossman was an aggressive, commercially-minded manager who helped turn Dylan into an extremely lucrative act. “He was very protective of every dime Dylan could make,” Siggins says.

Grossman’s profit-first mindset made him somewhat unappealing to some of more idealistic figures on the folk scene: Music critic Michael Gray memorably describes Grossman as “a pudgy man with derisive eyes … many people loathed him. In a milieu of New Left reformers and folkie idealists campaigning for a better world, Albert Grossman was a breadhead, seen to move serenely and with deadly purpose like a barracuda circling shoals of fish.”

Meanwhile, Mitch Greenhill’s father, Manny, continued to manage most of the artists in the Cambridge scene. Greenhill was a manager in a rather different mode from Grossman who was a child of the depression who’d put in work in the shipyard and was politicized by the Spanish Civil War in the ‘30s.

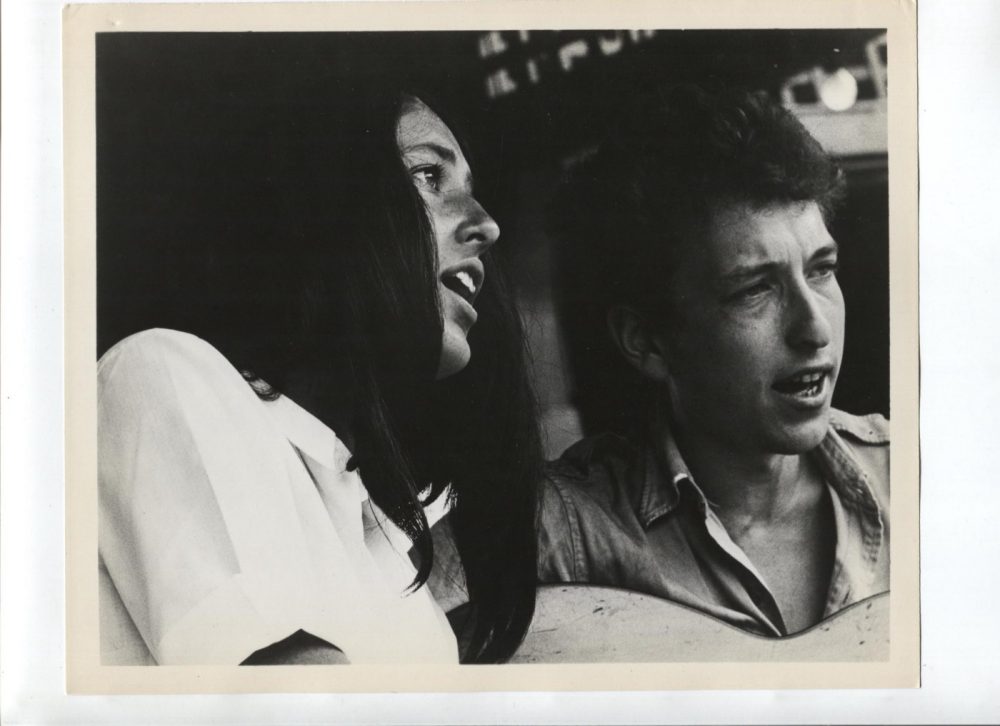

Grossman and Greenhill sparred over their clients in the mid-1960s. Grossman got Dylan, but Greenhill kept Joan Baez, who he had first heard sing at an anti-nuclear war rally led by her father — the prominent Boston-based physicist Albert Baez — when she was just a teen.

In 1965, the managers collaborated on a double-bill tour for their two stars, but there was tension on both sides, and Dylan end up profiting more from the tour than Baez. David Hajdu’s book includes Dylan giving a sort of proto-Trumpian dismissal of the Cambridge manager:

“Manny Greenhill — he’s such a loser. You know, such a stone loser. I worked for the cat, I did [those] concerts with Joan Baez. And would you believe this — I wasn’t big then really — not really big. I made more than she did, because he just had his ass up his neck. He did not know, Albert tried to make a deal with him, and he came on like a businessman … and Albert said ‘okay’ and stuck it [to] him.”

When Dylan would come back to Cambridge, Grossman had no interest in his playing at the tiny Club 47, which only charged a dollar for admission when most other venues Dylan could play charged $5. Grossman forbid Dylan from promoting shows at the Mount Auburn club.

Still, Dylan didn’t just fall in line with Grossman’s commands. Whenever he was in town, he’d show up at the club. Promoting his shows on Mount Auburn Street by word of mouth alone would bring huge crowds within minutes.

Siggins admits that the size of the Dylan crowd in the mid-'60s might have been more than the tiny club could handle: “The idea that 200, 300 people might pounce on the door of Club 47 was a little bit daunting to us.”

Yet even as Dylan’s reputation grew beyond the capacity of Club 47, Siggins and others from the Cambridge crowd remained in close touch with the rising star.

Siggins says whenever he would come back into town, “we would gather as an informal cadre of friends of Dylan.”

Sometimes they would go out with him on gigs and goof around. The photograph of Dylan on the roof of a car on Mount Auburn Street, for instance, came from a spontaneous trip with Dylan’s roadie, Victor Maymudes, “He just found it amusing to get on top of that car.”

Other times, he could be appear serious and determined: “He spent a night or two at my house and would sit up all night at the typewriter, writing lyrics,” Siggins says.

The Cambridge crowd was also there on the infamous night when Dylan “went electric” at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

“I remember being in the room with Dylan and Johnny Cash at the Viking Hotel,” Siggins says. “They were trading songs, smoking cigarettes, and nervously twitching their feet — both of them had that disease where they couldn’t keep one leg still. Before Dylan went on, Mimi Fariña, Maria Muldaur and myself were backstage. When the booing began, we were personally upset by that. The reaction was not what we thought.”

Mitch Greenhill, who was also at the concert, wasn’t surprised that Dylan would come in with an electric band. The whole thing, he says, was blown out of proportion in retrospect; most of the blame for the show should go to a bad mic set-up that wasn’t equipped to record an electric group, and Dylan still finished strong with his acoustic rendition of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.”

“We got that message loud and clear.” But, Greenhill says, “[Dylan] was clearly not in a good mood.”

In a rare moment of vulnerability, Siggins remembers that “Dylan came back down and sat down in my lap and didn’t say a word.”

Dylan became more distant from the folks in the Cambridge scene in the years that followed.

“When he moved to California, he was just on the road all the time. He traveled a lot when he was younger, but it was different now.”

Siggins says she’s been to some of his Boston shows over the last 10 years. “We would go back stage and chat for a few minutes. but he’s a man on a mission now. His private time is so limited now. He does his big Boston gigs and leaves.”

Schmidt and many of the other folk artists who hung around the Club 47 never achieved quite same level of fame as Dylan or Baez.

Siggins suggests, in Schmidt’s case, that he didn’t have the same goals as Dylan, “I just don’t feel like he was ambitious. He was good at what he did.”

Greenhill says, “Eric actually was ambitious, but he didn’t want to tailor his music to a preconceived notion.”

Another big obstacle was the closing of the original Club 47 in the late '60s after the venue ran into financial trouble.

“When the club closed, these people kind of lost their lifeline to that community," Siggins said. "A lot of people went to Berkeley and the Village, but the folk scene as we knew it was no more."

Club 47 would later open as Club Passim, which still stands today at 47 Palmer St., but the momentum had slowed. “There was a distance at Passim when it opened,” Siggins says. “There was a distance between that unbridled glory and the beginning of Passim in the '70s.

“There are mixed feelings all around there,” Greenhill says of the relative lack of exposure for the Cambridge scene. “We felt that we were on the true path, but we were impatient that the rest of the world couldn’t see that, so when that wasn’t totally fulfilled it was frustrating. But when it was its own cultural moment it was valuable.”

There’s no marker for Dylan’s spot on “the green pastures of Harvard University.” And the Club Passim, which still hosts folk acts and continues the legacy of the Club 47 today, does not try to put the legacy of its past on display.

“It walks and talks on its own,” Siggins says. “I don’t think it needs more publicity. I was there for 12 years [as Club Passim executive director 1997–2009]. Those were leaner years, it was tough going. Folk music fell out of favor, but they kept the doors open.”

The fact that there are still archives preserving the stories of the scene and musicians bringing new music to the club in its current incarnation may be enough.

“If you survive,” Siggins says, “things can come around.”

After the Nobel ceremony, maybe Dylan will come around the square again too.

Listen to the Open Source with Chistopher Lydon program on Dylan and the Nobel prize, featuring Sir Christopher Ricks, Francine Prose and Charles P. Pierce here.