Advertisement

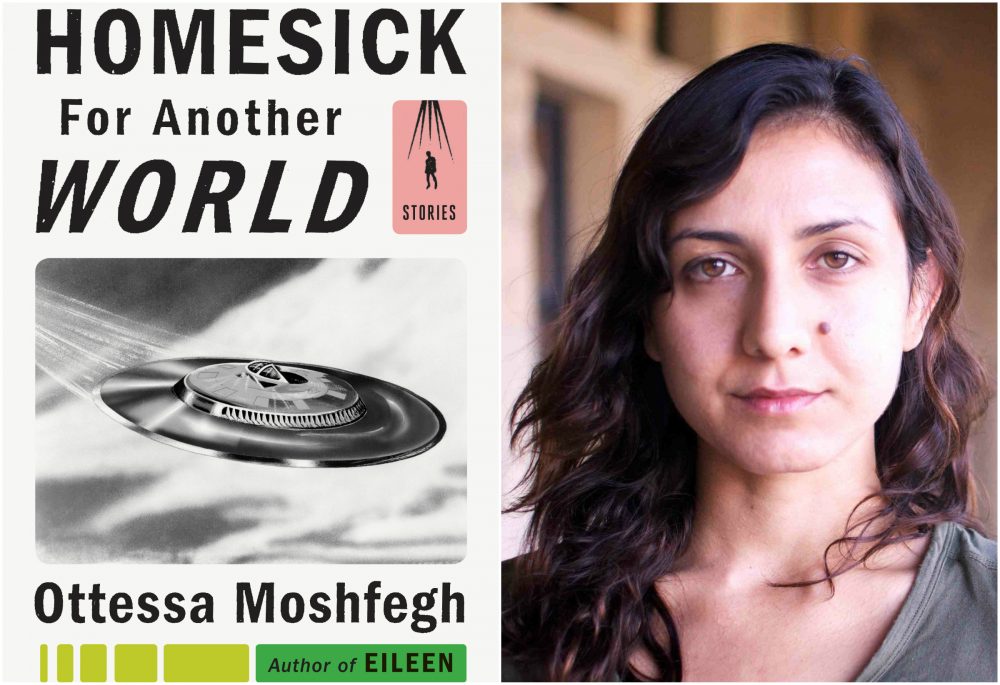

Though Exceptionally Written, Ottessa Moshfegh's 'Homesick For Another World' Gives No Relief

With the publication of her new short story collection, "Homesick for Another World," I suspect many reviewers will start describing Ottessa Moshfegh as the Diane Arbus of literature.

Like photographer Arbus’ subjects — the circus freaks, the disabled, the odd and the alarming — Moshfegh’s characters are the people from whom we avert our gaze. They are, to use that common but repellant term, "losers," and there is a dreadful sameness about them from story to story in this disturbing, exceptionally written, but ultimately unenlightening collection.

Two are substance-abusing teachers who hate their jobs and themselves; two are bachelors and one a married man fleeing his pregnant wife ("to have one last weekend to myself before the baby was born and my life as I’d known it was forever ruined") who debase themselves and others with cruelty borne of loneliness. Two are clueless would-be actors without insight or talent, and scattered throughout are indolent young people who lack the energy to engage in anything more ambitious than petty theft and mooching. Even the initially appealing ones, such as the widowed Larry, a seemingly kind man who raises tiny succulents and works in a home for developmentally delayed adults, who tells us early in “No Place for Good People,” “My poor wife. I didn’t know how little I loved her until she was dead.” It’s only in “A Better Place,” the dreamy last and most compassionate story clearly inspired by Hansel and Gretel (had they been real and possibly born as crack babies), that we are introduced to one of the very few sympathetic protagonists in this book, and she’s a homicidal child.

The protagonist of "Eileen" (Moshfegh’s last novel, which was a National Book Critics Circle Award nominee and won the PEN Hemingway Prize for debut fiction) was an anorexic alcoholic, and many of these stories’ narrators are similarly preoccupied. They compulsively squeeze their own pimples, bite their lips until they bleed and stick their fingers down their own or others’ throats. With a few exceptions, they make no progress either in reconciling themselves to their own lives or in changing them, and achieve no epiphany, just the occasional triumphant fantasy or moment of relief.

And when not engaged in self-abuse, what do they do? Not much. One teacher takes money from her ex-husband to stop phoning him; the other watches a pregnant teenager miscarry while cleaning her house. An unemployed young man studies himself in a mirror, grudgingly mows his dying uncle’s lawn, degrades the women he sleeps with and describes the man whose largesse he exploits this way: “All he did was watch TV or talk on the phone or eat. He loved game shows and cooking shows. I’m not saying he was an idiot. He was just like me: Anything good made him want to die. That’s a characteristic some smart people have.”

In theory, Moshfegh’s stories should be darkly comic. A developmentally delayed man’s birthday outing to Hooters is thwarted when the restaurant has been converted to a Friendly’s. An angry widower nearly drowns when trying to dispose of his wife’s ashes. A love-struck young man moves heaven and earth to buy an ugly ottoman and inadvertently destroys property and lives in the process. But they’re not funny, because what binds most of these characters is contempt, for others and for themselves, as in this excerpt from “The Weirdos,” in which a young woman considers leaving her meth-addicted boyfriend, an aspiring actor and building superintendent, but then doesn’t: “He always hid his shame and self-loathing under an expression of shame and self-loathing, swinging his fist back and forth, ‘shucks,’ always acting, even then. I don’t think he ever experienced any real joy or humor. Deep down he probably thought I was crazy not to love him. And maybe I was. Maybe he was the man of my dreams.”

Moshfegh repudiates the traditional narrative arc, presumably because unlike literature, most real lives don’t unfold in a pattern of stasis-triggering event-journey-obstacles-conflict-climax-ephiphany-resolution. Indeed, she toys with this convention, often setting us up to think that at last this repellent character is going to connect with some shard of inherent goodness, or is going to discover and act on some aspiration that will lift her out of her trough of despair. And then she kicks those expectations right out from under us. In these stories, change, when it happens, generally looks and feels like someone clinging by his or her fingertips to the edge of a crumbling cliff.

When looking at Diane Arbus’ photographs, you get the impression that she was trying to be unblinking and judgment-free, but the impression is false. In at least some of her photos, she chose her moments, waited for her ordinary subjects to look most defiant or grotesque, then captured them with vivid clarity. Like Arbus’ eye, Moshfegh’s voice is singular, dynamic and as invasive as a parasitic mite. She’s an exceptionally skilled writer, capable of great lyricism, sneaky wit and creating hauntingly vivid scenes.

I wish I could say that the discomfort of reading this book was worth enduring. But it wasn’t, not for me. By the end of the book I felt exhausted and infested, wishing that Moshfegh liked unsettling her readers a little less, and liked her characters a little more.

Ottessa Moshfegh with be doing a reading at the Harvard Book Store in Cambridge on Thursday, Jan. 26, at 7 p.m.