Advertisement

The A.R.T. Revives Tennessee Williams' Rarely Performed 'Night Of The Iguana' With All-Star Cast

Tennessee Williams is, of course, one of our great playwrights. And his two greatest plays — "The Glass Menagerie" and "A Streetcar Named Desire" — get produced often. Over and over.

I have to admit, I don’t look forward to seeing either of them anymore. And if I needed to, I would just as soon watch the movie versions. I know in advance that I will be blown away by Marlon Brando as Stanley Kowalski and Vivien Leigh as Blanche DuBois in “Streetcar” (talk about electrifying chemistry!). And in the first movie version of "Glass Menagerie," it’s fascinating to see the great British comedy and musical comedy star Gertrude Lawrence (“Private Lives,” “The King and I”) in a rare serious and even unpleasant performance as Amanda Wingfield, the aging Southern belle heroically and relentlessly trying to run her children’s lives.

Several other Williams plays also turn up with regularity: “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” “The Rose Tattoo,” “Suddenly Last Summer.” And their screen adaptations, although watered down, include astonishing performances (Elizabeth Taylor, Katharine Hepburn, Anna Magnani).

What I’d rather see are the good, juicy Williams plays that don’t get done nearly as often. So I’m really looking forward to the American Repertory Theater's approaching production of “The Night of the Iguana” (Feb. 18 - March 18) — the moderately successful 1961 Broadway play that’s both one of Williams’ stranger creations and one of his most central.

The action takes place in the short time beginning immediately before and ending just after the night referred to in the title (perhaps Williams’ nod to the Aristotelian “unities” of time, place and action). An Episcopal priest, the Rev. T. Lawrence Shannon, who has been locked out of his church when he suffers something like a cross between a nervous breakdown and a crisis of faith, is now at the end of his rope. A guide for a sleazy tour company, he brings a busload of Baptist teachers and the oversexed teenage niece of one of them to a rundown hotel near Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, operated by an old friend. He’s trying to avoid the advances of the teenager, who keeps placing him in increasingly compromising positions. The ladies on the tour, especially the girl’s “butch” aunt, Miss Judith Fellowes, a voice teacher, don’t believe or even want to believe his protestations of innocence and regard him as a degenerate and a rapist. The aunt, angry and also jealous, wants to report him to the American authorities.

Advertisement

It turns out the friend Shannon so desperately needs for support has died recently, and the hotel is now in the hands of his blousy widow, Maxine Faulk, and her hunky local cabana-boy “helpers.” Also just arriving are Hannah Jelkes, a very proper itinerant artist from Nantucket, and her grandfather, “Nonno,” a 97-year-old poet who hasn’t finished a poem in decades. All these characters are at their end of their respective ropes, including — literally — the large and helpless iguana the cabana boys have trapped and are fattening up for slaughter.

The heart of the play is the unlikely spiritual intimacy Hannah and the reverend find with each other in a series of dialogues — charged, emotionally complex confessions of despair (Shannon calls it “Man’s inhumanity to God”) and the possibility of contending with that despair, possibly even overcoming it. Each of them sees in the other a mirror of his or her own failures. And their conversations, rising above what Nonno calls in his poem “the earth’s corrupting love,” are among the most deeply poignant and personal in all of Williams. “Some people take to drink,” Hannah tells the drunken Shannon, “others take a pill. I just take a few deep breaths.” “Nothing human disgusts me, Mr. Shannon,” Hannah confides, “unless it’s unkind, or violent.”

In the original production, directed by Frank Corsaro, the leading roles were taken by Patrick O’Neal, Margaret Leighton (who won that year’s Tony Award as Best Actress), and — in the last of her rare appearances on Broadway — no less than Bette Davis as the wise-cracking Maxine, who has never gotten over her craving for Shannon (when Davis left the show, she was replaced by Shelley Winters). A 1976 New York revival at the Circle in the Square included Richard Chamberlain as Shannon, Dorothy McGuire as Hannah and Sylvia Miles as Maxine. And 20 years later, a Chicago production at the Goodman Theatre moved to Broadway starring Marsha Mason as Maxine and Boston favorite Cherry Jones as Hannah.

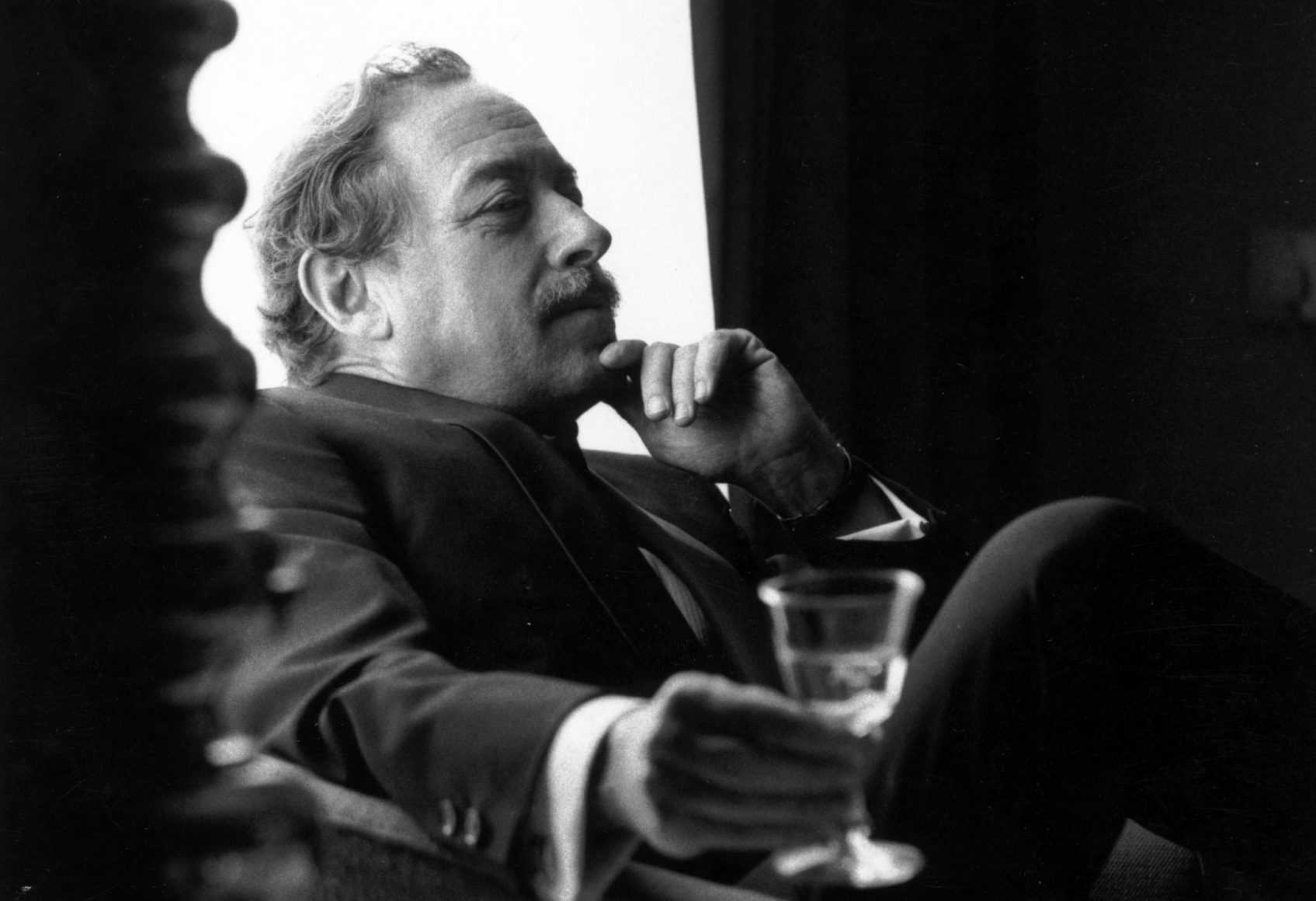

“Night of the Iguana” is probably best remembered from its 1964 film version directed and with a screenplay co-written by John Huston. The cast was spectacular: Richard Burton at his most eloquent and dissolute, Deborah Kerr at her most luminous, and — in one of her most genuine and moving performances — Ava Gardner as the raunchy Maxine (she was nominated for both BAFTA — British Academy of Film and Television Arts — and Golden Globe awards). Seventeen-year-old Sue Lyon, best known as Lolita in Stanley Kubrick’s film version of the notorious Nabokov novel, is yet another young seductress here. The movie won an Oscar for best black-and-white costume design; its only Oscar nomination for acting went to Grayson Hall as the bitter lesbian voice teacher.

The film made money, possibly helped by the gossip about Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, not yet married, who visited him on the set in Puerto Vallarta. Another visitor was the playwright himself, who contributed welcome suggestions solicited by Huston. In March 1964, Time magazine reported that at an award dinner for Huston, comic songwriter Allan Sherman sang a parody of "The Streets of Laredo" that went:

They were down there to film "The Night of the Iguana"

With a star-studded cast and a technical crew.

They did things at night midst the flora and fauna

That no self-respecting iguana would do.

During the filming, President Kennedy was assassinated.

Neither I nor the A.R.T. have any recollection of any previous Boston productions of "Iguana," at least not in recent memory. So this new one should be of considerable interest to Tennessee Williams admirers. And since the play has such glorious opportunities for actors, it’s good to see a cast with such outstanding credentials. Elizabeth Ashley, no stranger to Williams, will be playing the voice teacher Judith Fellowes. In 1974, Ashley was nominated for a best actress Tony for her performance as Maggie the Cat in a major Broadway revival of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” and she was a memorable Amanda in A.R.T.’s 2001 production of “Glass Menagerie.”

Popular Broadway, regional theater, film and TV actor Bill Heck is playing Shannon. Two-time Emmy Award-recipient Dana Delany (“China Beach”) appears as Maxine. And the wonderful Tony and Emmy Award-winning Amanda Plummer (probably most widely recognized as Honey Bunny in “Pulp Fiction”) plays Hannah.

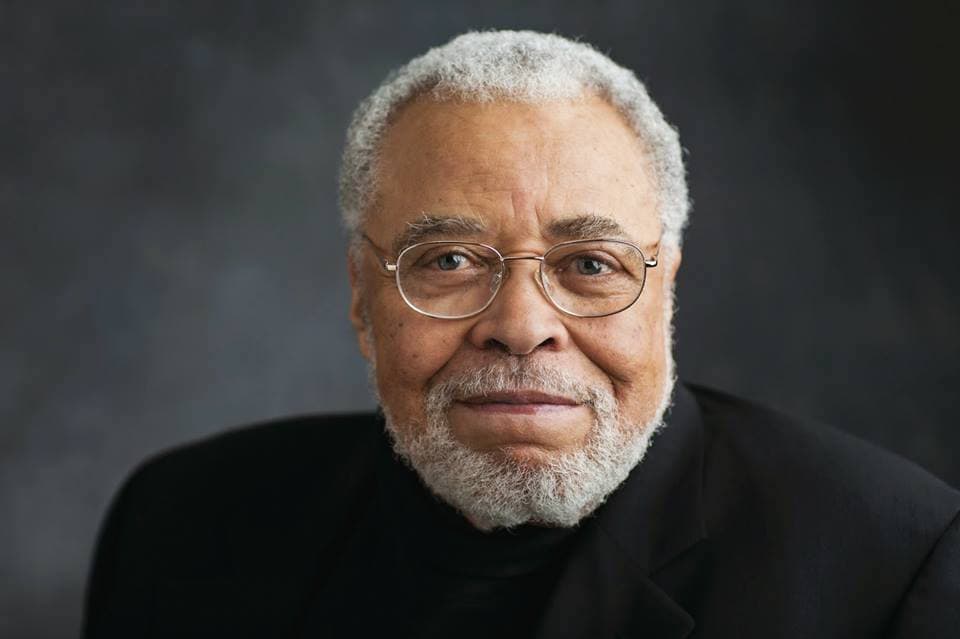

But the piece of casting that will probably capture the most attention (and sell the most tickets) is the legendary James Earl Jones as the aged Nonno. The voice of Darth Vader has the most epiphanic moment in the play when he finally recites the poem he’s been trying to finish for decades — a prayer for us to show the courage of the natural world in the face of our own human mortality:

And still the ripe fruit and the branch

Observe the sky begin to blanch

Without a cry, without a prayer,

With no betrayal of despair.O Courage could you not as well

Select a second place to dwell,

Not only in that golden tree

But in the frightened heart of me?

No surprise that some performances are already sold out. (For more information, visit the A.R.T.'s website.)