Advertisement

In Memoir, Lol Tolhurst Tells What It Took For The Cure To Get To Top Of '80s Alt-Rock Universe

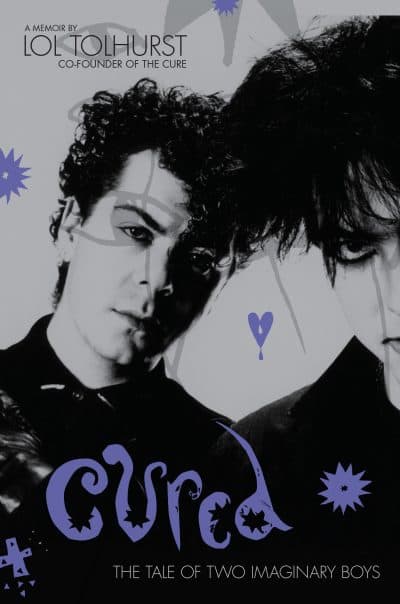

If ever you want to get inside The Cure — one of the most artistically and commercially successful bands to come out of post-punk Britain — Lol Tolhurst’s new memoir is your go-to source. "Cured: The Tale of Two Imaginary Boys" tells the story of how he and his best friend, Robert Smith, created this little band in a drab London suburb named Crawley and brought it to the top of the alternative rock universe during the 1980s.

“I remember going to see The Clash with Robert at our local sports center,” says Tolhurst, clad in a black top and jeans one recent afternoon at Boston’s Hojoko restaurant. He was just a teen and not yet in a band. “It was maybe their second or third tour and it was just like, ‘Yeah, I get this.’ ”

Tolhurst took drum lessons from a local big band jazz drummer and Smith took guitar lessons from a blues guitarist he met in the street. Smith, of course, is the singer, main songwriter, guitarist and the face of The Cure — the one constant member from Day One. But, Tolhurst says, "I get the feeling I’m the only person within the whole Cure camp who will ever write about the band. Robert’s kind of like Bowie; he’s never going to want to reveal that much of himself. I said to him, ‘Are you going to a write a book one day?’ and he said, 'Well, maybe a 16-page comic.' "

"I realize to be a successful musician you have to have several things: You have to have some talent, you have to be in the right place in the right time, but you also have to have an ability to live through the extreme highs and the extreme lows..."

Lol Tolhurst

Tolhurst was in the band — first as a drummer, later a keyboardist — from 1976 to 1989 (and then again for the nine-date “Reflections” tour in 2011). Their other childhood chum, Michael Dempsey, played bass in the early days. All three wrote the songs that would comprise their first, and rather poppy, album “Three Imaginary Boys” in 1979, retitled “Boys Don’t Cry” and slightly rejiggered for U.S. release in 1980.

“We said ‘Let’s go make a record. We can pay ourselves 25 pounds a week each, and next month maybe we’ll be back working in a [day] job.’ That was 40 years ago, and I’ve never done it since," says Tolhurst. "When I look at it that way, I realize to be a successful musician you have to have several things: You have to have some talent, you have to be in the right place in the right time, but you also have to have an ability to live through the extreme highs and the extreme lows without going ‘Oh s---, I wish I could have a normal life.’ I don’t do well in normal life for a long time.”

He also didn’t do well in The Cure during the latter part of the ‘80s, but more on that later.

Tolhurst says the band’s gift for melody “is how things like ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ [the album’s hit single] came out because although we had the ability to make something poppy, that wasn’t really our first love. But we wanted to get noticed. And it worked. Also with the first album, we didn’t know how to produce our own records so we went in, recorded it and we sat at the back of the studio and said ‘OK, we’ll drink beer while you do it.’ ”

Advertisement

That “you” was Chris Parry, who managed The Cure, produced that 33-minute debut LP and co-founded the label that was the band’s home for 20 years, Fiction Records.

“Robert might disagree with me on this because he tends to dismiss Chris Parry’s involvement,” says Tolhurst, “but I think one of the things that Chris did that was really genius was — we came in with the songs for [the second album] ‘Seventeen Seconds’ and he understood — thinking, ‘Well, they’re not really poppy or anything, but OK, let’s see where it goes.’ ”

“Seventeen Seconds” and the follow-up, “Faith” are atmospheric, moody masterpieces. Smith wrote the lyrics; the music was spread among all members, which now included bassist Simon Gallup (replacing Dempsey). Keyboardist Matthieu Hartley was there for the first album, but gone for the next, the band reverting to trio form.

The best punk rock was an explosion of anger and celebration. The Cure’s music carried a sense of resignation; it was dark and dreamy in a Pink Floyd sort of way. It was minor-key melodic and resolutely melancholic — the sound of things falling apart, ever so gracefully, with chiming three-note guitar licks and whooshing synthesizer lines. Smith's voice was a moan, a sigh.

“When I heard the first skeletal demos that Robert had for ‘Seventeen Seconds,’ ” says Tolhurst, “I said ‘I know exactly what this is and this speaks to me.’ Also, we played all those songs for three years before we recorded them.”

Those two albums are minimalistic, but infused with these gorgeous lush washes of sound. Both musically and lyrically, The Cure created what some have called "gloomscapes" -- introspective songs of regret, longing and ennui. Nothing celebratory. Simple, but seductive.

“Part of it came from our youthful inability [to play],” says Tolhurst, “but part of it came from our own desires to make things that worked. There are loads of bands imitating the kinds of music they like. We just said, ‘What don’t we like?’ Long lead guitar solos and very flamboyant drum fills. We’re not going to incorporate them so there’s no point in learning how to do them.

“Also, [we were influenced by] the records that came out around that time, like Bowie’s ‘Low’ in '77. And we also heard people like Nick Drake. He had a very melancholy sound that had a big hole in the middle — like his voice was up here and then there’s all the cellos and stuff and there’s this big aching hole in the middle. We liked that.”

The Cure followed with harsh-sounding album, “Pornography,” but on subsequent albums reactivated their pop sensibility. They climbed the charts, got played in new wave clubs and began playing arenas, spurred by hits like “Let’s Go to Bed,” “The Love Cats,” “Friday, I’m In Love,” “In Between Days,” “Just Like Heaven,” “Why Can’t I Be You” and “Fascination Street.”

In 2015, Tolhurst decided he wanted to write his version of events. He had read about 50 memoirs before starting to tackle his in an office near his home in Los Angeles, where he’s lived for 23 years.

Listen to Tolhurst narrate an excerpt of his memoir in the audiobook version:

Most rock memoirs he says, mentioning Morrissey’s in particular, “just turned into very sad score-settling exercises.”

There could be the expectation that Tolhurst, who’s now 58, might have set out to do the same. After all, he was demoted from full band status and then fired by Smith in 1989. He then brought a very expensive and unsuccessful lawsuit against Smith.

It’s not that Smith didn’t have cause and Tolhurst concurs in the book. Tolhurst’s contributions became less and less over time; moreover, his drinking and drugging had caught up with him. He’d been a blackout drunk in his youth, but it was getting worse.

Smith told me this early in 1989 for a Boston Globe story, after The Cure had released their “Disintegration” album: "We'd grown apart too much to work together anymore. It had been building up, or I suppose breaking down, for two years really and I said if he didn't come around I couldn't stand it. I wanted there to be a kind of intensity within the group, try and work ourselves back up to the emotional level we haven't really had for a few years. He didn't want to be there, didn't accept it. On the 'Disintegration' sessions he sat and watched MTV during most of it.'”

It's not as if the rest of The Cure were absent from the world of intoxicants. “I’m not sure if we were in the same boat,” says Tolhurst, “but we were probably using the same oars and we were definitely rowing in the same direction. It’s just I was the one that hit the iceberg.”

Tolhurst — now sober 27-plus years — has his regrets, especially the lawsuit. It cost him not only Smith’s friendship — for a time — but $1 million, the English courts garnishing 75 percent of his income, taking a decade to pay off.

“I wasn’t well mentally,” Tolhurst continues, of when he filed suit. “I did think up the [band’s] name and we were partners — I just wanted the partnership to be wound up correctly. More than anything, what happened was I went to rehab and got sober, but didn’t do the work of sobriety, which is getting rid of all those resentments which dragged you into that place in the first place. So, the court case was one gigantic resentment that I took all the way and once you get past a certain point in law it’s like this unstoppable juggernaut that’s racing to a conclusion.”

The Cure continued, making five more studio albums through 2008, but nothing since. They are still, though, a touring band and played Boston last summer.

When he became solid in his sobriety, Tolhurst began the process — key in 12-Step programs — of making amends. In the winter of 2000, he wrote Smith a long letter, apologizing and explaining. When The Cure played The Palace in Los Angeles, Tolhurst was able to get backstage and meet with Smith.

They hugged and rebonded. Did Tolhurst consider it a cleansing experience? “Absolutely,” he says. “You have to do it. My understanding now is if I hadn’t have done that, hadn’t righted the wrong, real or imagined, eventually I would go back to drinking, go back to that destructive area.”

In 2011, Smith decided to bring various members of The Cure back together for what turned into a nine-date stretch, called the “Reflections” tour, playing everything from their first three albums (plus a few more). There were several post-show parties. “Simon and Robert would drink a little bit but not like the old days,” says Tolhurst. "You can’t. When I got backstage for the first time I went 'Where’s the vodka bottles?' "

Tolhurst still thinks of The Cure as a punk rock band. "What mattered to us then and still matters to Robert -- and I know because I talked to him last year — is punk for us was not a musical style. It’s more to do with how you thought about things, how you did stuff and how you worked. That’s what we admired and still what we ascribe to."

He has kept making music over the years. Tolhurst just started working on a film soundtrack with his friend, guitarist Porl Thompson, a one-time Cure member, too. Tolhurst formed the quartet Levinhurst in 2002 with his wife Cindy Levin and original Cure bassist Michael Dempsey. They've released three albums and two EPs — and Tolhurst says they will be active next year.

When he saw The Cure in LA last May, he gave Smith an advance copy of "Cured." "I had told him from the very beginning," says Tolhurst, " 'Don’t worry. I know where all the bodies are buried and it’s fine because that’s not the purpose of the book for me’ and he said 'OK.' We laughed. I know him well enough to know that if there was something he didn’t like he’d have let me know [by now].”

Would he like to rejoin The Cure?

“I’ve thought about that a lot,” Tolhurst says, “because a lot of people who’ve read the book go ‘Oh, it’s like he’s asking to be back in the band.’ No, that’s not it at all for me. My life is open enough that if Robert calls me up and says ‘We’re going to do this, do you want to come along?’ I would say probably ‘Yes.’ But it’s not my driving force. I’ve been so long apart from it.

"When I went back in 2011, even though we did only a handful of shows we spent most of a year working up to it, spending a lot of time rehearsing, on and off. And it was enjoyable but it also wasn’t what it [once] was. It had moved on to somewhere different."