Advertisement

'Hidden Figures' Of Astronomy At Harvard Take Center Stage In Play About Women 'Computers'

Resume

It seems women “computers” are having a pop-culture moment. There’s the hit Hollywood movie, “Hidden Figures,” and also a new non-fiction book titled, “The Glass Universe,” which is about the pioneering female computers at the Harvard College Observatory.

Now those women’s stories are being dramatized in a local production of the play, “Silent Sky.” I visited the Watertown-based Flat Earth Theatre company’s rehearsal to explore why and how these revived stories are resonating today.

Early in the play the main character, Henrietta Swan Leavitt, arrives eager to start her job at the Harvard Observatory. But the star-gazing, Lancaster-born Radcliffe grad is confused by her job title.

“What’s a computer?” Leavitt asks two of the women she’ll be working with. Annie Jump Cannon replies, “One who computes.” Williamina Fleming elaborates, “Notate the plates, transfer the data, input the data, process, record, next star.”

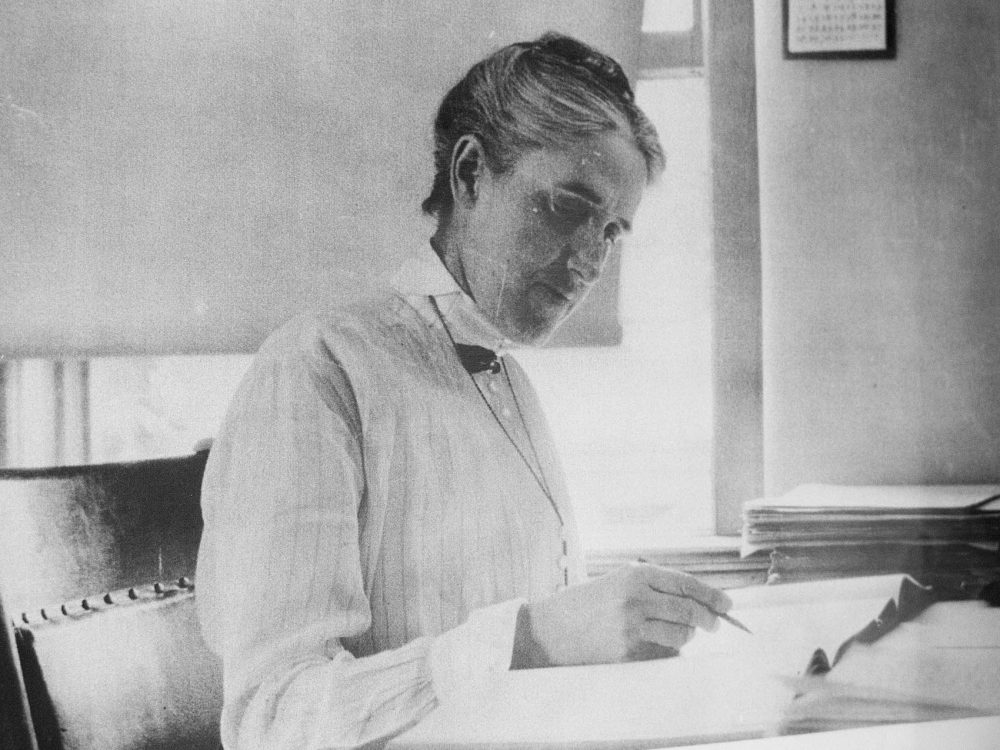

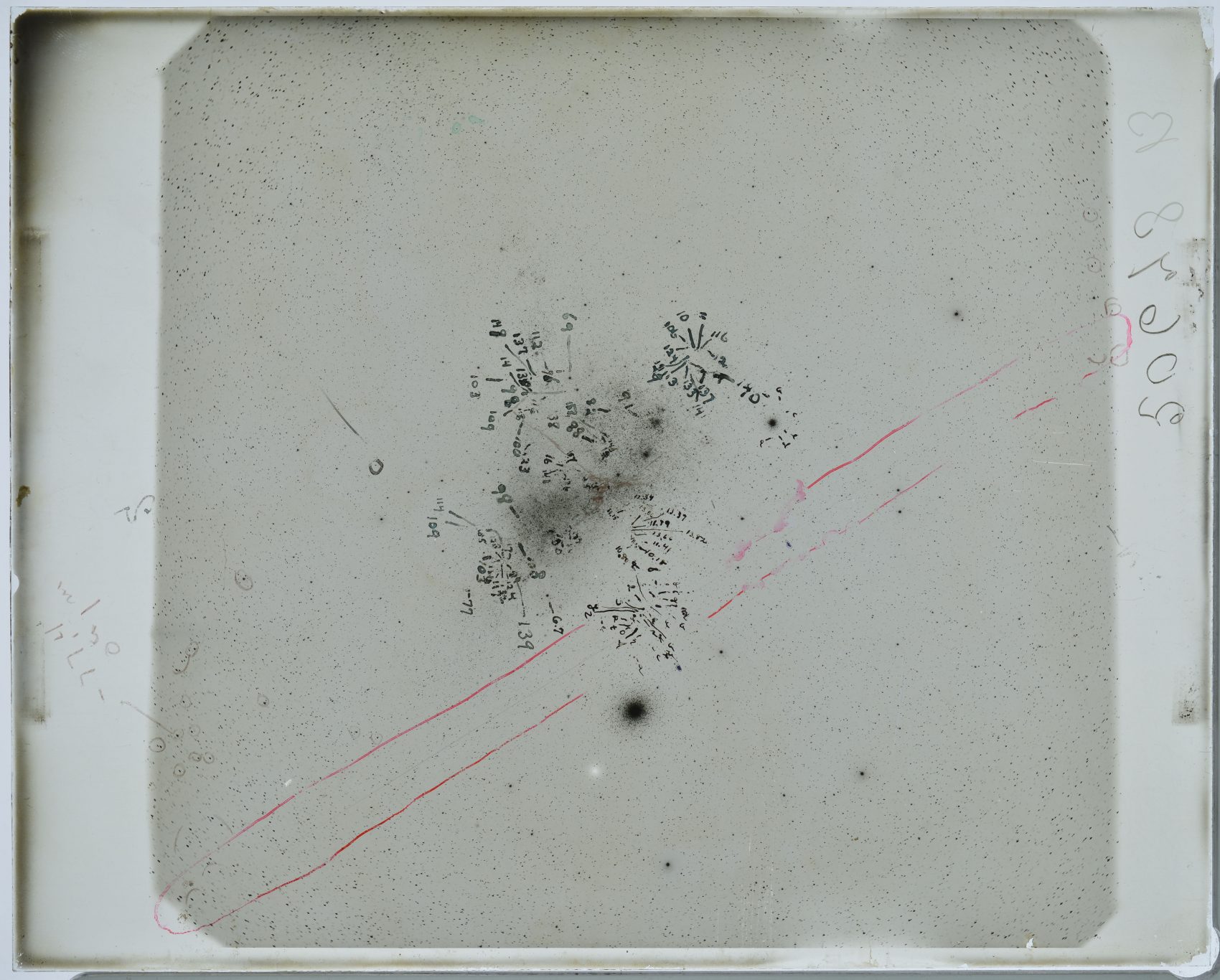

These two characters are inspired by the real women computers who worked at Harvard in the late 1800s and early 1900s. They studied and documented glass plate images of distant stars and galaxies. The windowpane-sized photographic plates were captured by male astronomers using powerful telescopes, but it fell to the women to catalog them.

As Cannon’s character explains their charge, “We collect, report and maintain the largest stellar archive in the world. And we resist the temptation to analyze it.” Then Leavitt asks, “But you just said how much you've discovered here, both of you.” With a verbal shrug Fleming responds, “Eh, resisting doesn’t always work.”

The cramped rooms where these Harvard computers worked were just a short walk from a famed telescope with a 15-inch lens known as The Great Refractor. That elegant beast was the pride of Boston when it was installed in 1847. For 20 years it was the largest telescope in the United States. In the play Leavitt impatiently asks her (fictional) supervisor Mr. Shaw to show her the instrument.

“Is that it? The Great Refractor?” Leavitt asks excitedly. Shaw says, “Yes, but…" and Leavitt interrupts, “One of the largest in the world.” “I am very aware,” he responds a bit cockily, continuing, “Quite a point of pride for us. But, this is the workroom for you girls to work. Down here.”

In the play — and in reality — Leavitt and the other “girls” made ground-breaking discoveries using sparse resources in tiny offices that would shape the future of astronomical study, without touching that telescope. But their stories have remained largely unknown. “Silent Sky” director Dori Robinson wanted the change that.

She told me gender parity is part of what drew her and the Flat Earth Theatre to stage playwright Lauren Gunderson’s script.

“Because it was written by a woman, about women in science, and four out of the five characters were female,” Robinson said. "That's what drew me to open the first page. Because we do not have enough gender parity — in theater, in the arts — there are not as many women's voices as there are men’s.”

Robinson and Flat Earth obtained production rights for “Silent Sky” nearly a year ago. But soon they caught wind of a new movie about the African-American women computers who calculated flight trajectories for NASA during the space race in the 1960s.

“When I described to people what the show ['Silent Sky'] was about people said, ‘Oh, have you heard of "Hidden Figures?"' the director recalled. “And I only just recently saw it. And it's interesting to see, again, women who could crunch numbers, women who had these brilliant minds who are isolated in a room. So yeah, very fascinating that these women are finally getting their story told.”

Flat Earth Theatre has been producing plays about history and science for the past 10 years. Company member Lindsay Eagle said, “‘Silent Sky’ is so beautiful in that it is so scientific, yet so full of heart. It’s this play that really uplifts these women who are little known figures. Hopefully it will drive people to do more research about these historical figures — who are women — and that’s awesome.”

Erin Eva Butcher portrays Leavitt in "Silent Sky." The actress admitted she didn’t know anything about Harvard’s computers or her character before she took the role.

“I live in Somerville and I had been to the observatory before — but I had never been inside,” Butcher explained. “And when I got this part I read a book called, 'Miss Levitt's Stars,' and, 'The Glass Universe,' by Dava Sobel. Henrietta Leavitt is such a fascinating figure because there’s really so little known about her and she's kind of this mysterious woman.”

Leavitt’s biggest discovery is what’s known as the period-luminosity relation of Cepheid variables. In simple terms, she figured out how to measure distances between stars and galaxies by obsessively analyzing the glass plate images of the cosmos. In his book, “Miss Leavitt’s Stars,” author George Johnson called her, “The woman who discovered how to measure the universe.”

Butcher and the cast had the chance to visit the Plate Stacks, as they’re called, at the observatory where Leavitt and the other computers poured over a steady stream of collected data. Today the archive is part of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

“It was so amazing to get to go to the observatory and see the plates — actually hold in your hands the plates that Henrietta used to make her discoveries and the actual notebooks that she wrote in,” the actress marveled. “As an artist, you so seldom get to actually sit down with primary research like that, and things the people actually touched.”

I had the chance to see those glass plates, too, on a tour with Lindsay Smith, acting curator of the Plate Stacks. As she showed me around the modest, old rooms she stopped to remove a celestial glass plate image from one of the many tall, metal cabinets.

“Some plates it's very interesting because you can see that several different women were working on the very same plate that you have here," Smith said, pointing to the different styles of handwriting.

“I have a plate that's from Henrietta Leavitt,” she added.

Smith also brought out one of Leavitt’s now fragile log books and placed it in a special cradle. The astronomer’s meticulous handwriting fills its pages. Copies of faded photos and newspaper clippings about the computers cover a bulletin board. One headline reads, “Brainy Boston Woman Learns Skies Secrets.”

“There were many newspaper articles about them in the 1880s and early 1900s,” Smith explained, “and then they kind of just disappeared.”

Next, Smith took me across a courtyard to the observatory building and led me up an old, creaky spiral staircase. We were going to see the telescope that was off-limits to Leavitt and the other computers. No one uses it today. The curator and historian is encouraged that more people are interested in the computers’ stories.

“When I was growing up I hated history, actually, until I went to college and started studying women’s history,” Smith remembered, “and then I realized there were a lot of women that did amazing things in the world – it just wasn’t recorded, or it was lost to history somehow.”

Contemporary women astronomers also appreciate the attention the computers are receiving for their contributions. Meredith Hughes is one of them.

“For me it’s really funny — in the best possible way — to see the rest of society discovering a story that’s always been part of both my professional history as well as my family’s history,” she said.

Hughes is an assistant professor of astronomy at Wesleyan University and also the great-granddaughter of a former head computer at Lockheed Martin.

“The only thing that’s disappointing to me is that I’m actually going to lose one of my favorite classroom jokes,” Hughes mused, laughing. “I love to tell my students that my great-grandmother was a computer and watch them try to figure out if I’m serious or not.”

When Hughes was a grad student at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics she loved to visit The Plate Stacks. She told me that her great-grandmother was her role model.

“My great-grandmother rode horse-drawn trolleys into Harvard Square as a little girl, but then, by the end of her life, she was calculating satellite orbits,” Hughes said, adding that the history of female computers isn’t as old as we think it is. “So we see that in the stories of these female computers, and now we’re getting to hear their stories which we didn’t get to hear before.”

Hughes thinks this 21st century "moment" for the computers from our past speaks to the strides women have made in the sciences over these many decades. Looking ahead, she hopes to hear more stories about women of color in STEM-related field — like the ones celebrated in the film “Hidden Figures.”

“It both reflects how far we’ve come,” the radio astronomer said, “but also how far we have to go.”

"Silent Sky" is on stage at the Mosesian Center for the Arts in Watertown through March 25.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Henrietta Swan Leavitt was born in Cambridge, while "Silent Sky" notes that she was born in Lancaster. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on March 13, 2017.

This segment aired on March 13, 2017.