Advertisement

Boston Artist Ria Brodell Finds ‘Butch Heroes’ Buried In The History Books

After a couple years making paintings that rummaged around childhood memories of growing up Roman Catholic, of G.I. Joe and He-Man toys, of watching Rambo movies and old Hollywood musicals, in 2010, Boston artist Ria Brodell painted a gouache titled “Self-Portrait as a Nun or a Monk, circa 1250.” On the left, Brodell was in a nun’s habit. On the right, Brodell had a monk’s tonsure and brown robes.

“I was doing some portraiture of myself as an old man, kind of thinking of getting older, that led to doing my portrait as a nun or a monk,” Brodell says. “I was thinking about, as a gender nonconforming person, how in the past would I have gotten by? Would I have joined the Catholic Church as a nun? Would I have joined the Catholic Church as a monk? Because people did that too. I have no idea. It’s amazing what people did.”

This got Brodell wondering. “I was assigned female at birth. I consider myself nonbinary trans,” Brodell says. How would someone like that have made a go of it in the olden days?

The artist headed to the Boston Public Library in Copley Square. “First I went to the LGBTQ aisle and I was digging through the books trying to find stories,” Brodell says, looking for histories of people assigned female at birth, but who presented as masculine as they grew up, and had documented relationships with women. Mainly people who lived before the 20th century.

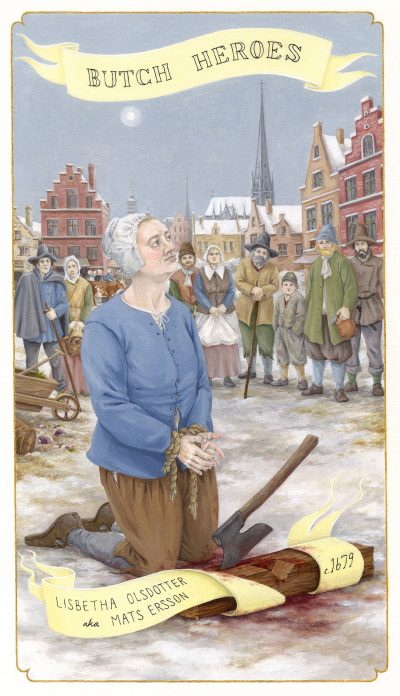

Brodell’s research led to the life story of Catharina Margaretha Linck aka Anastasius Lagrantinus Rosenstengel, who, Brodell reports, "was convicted of sodomy with a ‘lifeless instrument,’ for wearing men’s clothes and for being baptized multiple times" in 18th century Prussia. King Frederick William I ordered Linck beheaded and the body burned in 1721.

“They couldn’t figure out how to punish lesbians,” Brodell says, “so they just covered all their bases. It was ridiculous.”

Brodell painted a symbolic portrait — on view in the exhibit “Butch Heroes” at Boston’s Gallery Kayafas through April 8 — of Linck holding the chopped-off head in one hand and the “lifeless instrument” (faux male genitalia) in the other as a fire burns against a gold background. “I really got into the gory details of painting them. I think it goes back to the holy cards I loved as a kid — they were all gruesome.”

Your Cross To Bear

Growing up in Boise, Idaho, Brodell says, “My parents and my grandma would let me dress the way I wanted to dress. It was usually clothes that were probably meant for a boy, male clothes and a hat. I was dressed just like my brothers. They let me play baseball. I wasn’t into any of the stuff my sister was into.”

In high school in the 1990s, Brodell dug out a 3-inch-thick book of Roman Catholic catechism that the family kept on the shelf next to a dictionary of saints. It recommended that gay Catholics become nuns or priests and always remain celibate.

“I remember my relatives always using the parlance if there was a hardship that that was ‘Your cross to bear,’ ” Brodell recalls. “I remember that being in the book. Homosexuality was your cross to bear. I was like, ‘Great.’ ”

Brodell says, “It came to a head when I got to be a teenager and they saw it wasn’t a phase and I wasn’t growing out of it. Then I came out [at age 19]. There was a lot of tension, but … they came around and they’re fine now.”

Living The Lives They Wanted To Live

Brodell’s portrait of Linck was the first in what has become the “Butch Heroes” series.

Brodell had moved to Boston in 2003 to study at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, earning a master’s degree in 2006. From the Boston Public Library, Brodell continued researching “Butch Heroes” at libraries at Tufts University and Boston College, and online. Brodell learned the story of Katherina Hetzeldorfer, who was arrested and executed by drowning in 15th century Germany for living with a woman, “being like a man in both physique and behavior, a sexually aggressive character and a potent lover,” and using an “instrument” (again fake male genitalia).

Brodell found Elena aka Eleno de Céspedes, who reportedly had many affairs with women in 16th century Spain, professed to be a hermaphrodite, but officials alleged was a woman and illegally married to a woman. Charged with bigamy, fakery, perjury and mockery of the sacrament of marriage, Céspedes was given “200 lashes and was ordered to serve 10 years in a public hospital, dressed as a woman.”

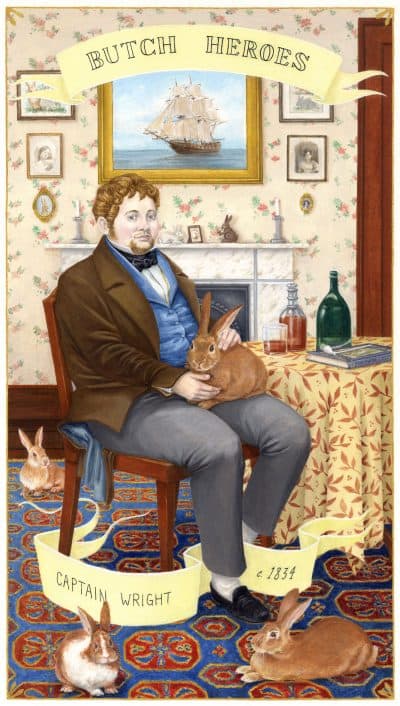

Brodell researched Captain Wright, known for enjoying drink and the company of women in 19th century England taverns. Wright’s death caused a sensation, when “the body was found to be female, a ‘beard only excepted.’ ”

“People who were upper class or born into wealthy families got a little leeway,” Brodell says. “The working class people seem to have had the worst of it, had to move from town to town. Most of them actually don’t end well.”

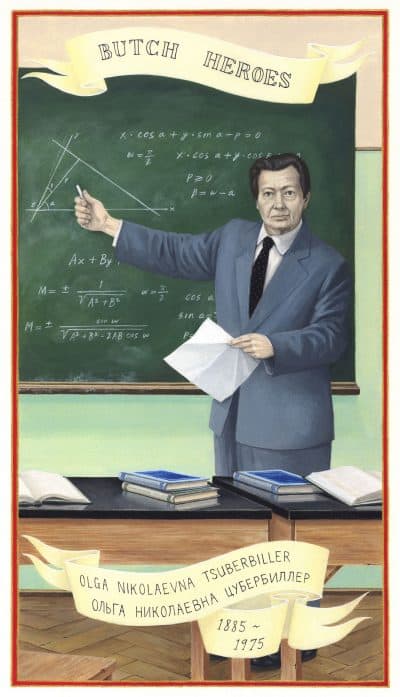

Brodell found some exceptions to the unhappy endings. Rosa Bonheur, “was granted permission by the police commissioner to wear men’s attire while painting,” twice married women and became a celebrated 19th century French painter and sculptor. Olga Nikolaevna Tsuberbiller found success as a 20th century math and science professor at Moscow State University.

“Is this because those two did well in their craft, made themselves respectable? I wonder if that’s why,” Brodell says. “Some like Katherina Hetzeldorfer, who was put to death, was described as aggressive and threatening and overly masculine. It could be the person’s personality. … Who knows?”

Brodell adds, “My guess is there were a lot of people I can’t find. Maybe they did have happy endings. There are people I can’t find because they’re not in the court records.”

“We as queer people have existed throughout time and even though these people have had harsh punishments, they put up with a lot. … There’s something heroic in that, and reassuring. I like the fight they put up,” Brodell says. “I like having this in your face proof that we’ve been around and even though we were maybe put to death or endured harsh punishments or demeaning public exposure, a lot of these people lived the lives they wanted to live regardless of that.”

From Saints To ‘Butch Heroes’

Working at home in Jamaica Plain and in a studio in Boston’s South End, Brodell painted the “Butch Heroes” in gouache (opaque watercolor) in the style of Catholic holy cards depicting saints that are often given out as memorials at funerals. Brodell remains inspired by a large collection of holy cards that an aunt assembled by putting advertisements in newspapers that attracted donations from all over — pictures of St. Francis surrounded by animals or St. Bartholomew, said to have been executed by being skinned alive, depicted carrying his skin over his arm.

“I don’t consider myself Catholic any more. It’s still in my system I guess,” Brodell says.

“I was given holy cards to teach me how to live and I did not identify with those people,” Brodell says. “When I got older and I realized how the church felt about me and how they wanted me to live my life, I was like, ‘What?’ I don’t know if I was angry or disappointed. Putting these people on holy cards that I identify with, it’s a subversive way to replace those role models that that Catholic Church gave me with people I actually identify with.”

Brodell continues to research and paint more “Butch Heroes.”

“These people, just as much as the saints, deserve our attention,” Brodell says. “We can learn something about ourselves, we can learn something about our culture in the way these people were treated in history. So many people have said to me, ‘Man, we treated these people terrible. We suck as a human race.’ But how much has changed?”

“I remember when I was planning this show, or even prior to that, over the past few years of gay marriage being legalized and trans rights gaining momentum, I remember thinking, ‘Maybe I don’t need to do this project any more,’ ” Brodell says. “It’s funny to think back that those thoughts were crossing my mind. Even since November, now it’s totally necessary. It’s disheartening to see the parallels to what happened in the Middle Ages to what’s happening now. Like the murders of all the trans women recently. Or trans rights we made so much progress on recently and now it’s all being pushed back. It’s disheartening. It’s a yo-yo. In a lot of ways, in the queer community, we made a lot of progress politically and maybe that political progress will get ratcheted back a little bit, but we did make that progress, and like a yo-yo it will come back.”

Brodell says, “I’m trying to be optimistic.”