Advertisement

Longtime Boston Jazz Booker Recalls Career Spanning 'The History Of Jazz'

Born and raised in Newton, Fred Taylor started going to shows in Boston as a kid, seeing big band legends that would lead him to a life in music. He says he "got hooked on jazz" with Dizzy Gillespie's "Salt Peanuts." Now 87, he's one of the most influential figures in Boston jazz.

Taylor has been responsible for bringing a who's-who of post-big band jazz to the area since his beginnings in the early 1950s.

He was launched into the jazz world after meeting pianist Dave Brubeck in 1952 at a show at Boston's Storyville. In a pinch, Taylor taped Brubeck's show on an amateur device, in a recording that was covered briefly in the New York Times and would ultimately be released on Fantasy Records.

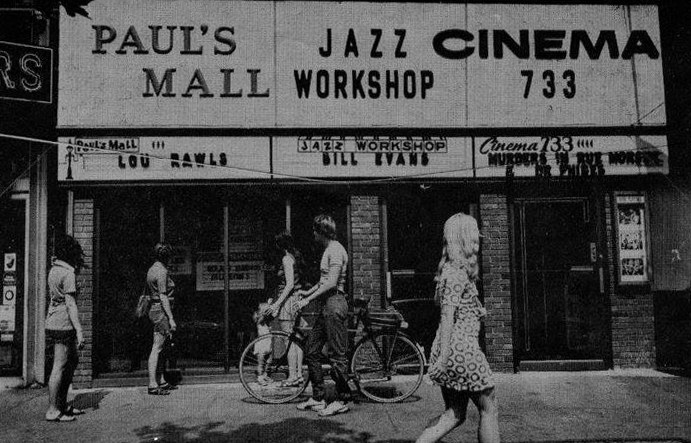

By the mid-1960s Taylor took ownership of Paul's Mall and the Jazz Workshop, two clubs located side by side on Boylston Street in Boston. Among the hundreds of musicians Taylor hosted at his clubs were John Coltrane and Miles Davis, who played more than 10 times at Paul's Mall and the Jazz Workshop, according to local jazz historian Richard Vacca.

Financial problems led Taylor and his partners to close the two clubs in 1978, with hopes of opening a larger venue that would yield better numbers. But that never came to fruition. Taylor went into movie theaters, running Harvard Square Theatre until he and his partners sold the business in the late '80s. He continued to book jazz acts during that period, perhaps most notably in 1981 with the comeback run of Miles Davis at the Kix Club in Kenmore Square.

Davis chose, at least in part, to start his comeback in Boston thanks to Taylor. In a 1981 Boston Globe interview, Davis said: "Every time I have a new band and a good band, I just come to Boston. Also, I wouldn't do it for anybody else but Freddie Taylor."

In 1989, Taylor became entertainment director at a new venue, Scullers Jazz Club, where he worked full time until he was fired earlier this year. Taylor continues to book shows in the area and says he has no plans of stopping.

I spoke with Taylor in his office in Boston's Allston neighborhood. Here's our conversation, lightly edited:

Help me with the math here. How old are you going to turn on June 8?

"Oh s---. My age? I'm going to be 88, which I absolutely cannot relate to. I mean it's a strange number: 88 — that's an old man, I'm not there. That's not me."

"I come in for an exam and they tell me: 'What to do, are you retired?' 'I say no no no, I'm working full-time.' 'What? You're working full-time?' They're amazed. My attitude, my mentality is, I'm like maybe 70."

How did you first get into jazz music?

"I was a jazz head, oh God, starting in high school, going to the RKO theater in Boston, which had movies and stage shows. They played all the big bands at the RKO, which I loved. So I'd go every Saturday morning. The first [show] was 11:30 in the morning. Unbelievable. That's where I saw Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five, Jimmy Dorsey, Lionel Hampton. I saw all the big bands."

"And then, as I got into college, I started hanging out at all that jazz clubs, and that's in the late '40s. Boston was a Mecca. At the corner of Mass. Ave. and Columbus was The Hi-Hat, Wally's Paradise, The Savoy, The Big M... It was humming."

You say your entry into the world resulted from a recording of a Dave Brubeck show on an amateur kit. How did that happen?

"An amazing thing happened in 1952. I go down to a Sunday matinee and I introduce myself to Dave. I said I would love to just get some recording for myself. He said 'Go ahead.' The bass player for some reason didn't make it that Sunday, so Dave played a little differently."

"At the end he says I'd like to hear what you got. ... So [we] jump into my car and drive to Newton. I was still living with my folks and I had a big hi-fi system. I plugged it in and he says, 'Wow, that's great. I'm going to be in New York all next week — could you make a copy and mail it to me?' "

"I sent it to him. I got a call [a few days later].... he says, 'You know, Max Weiss from Fantasy Records was here. He heard it and he wants to put it out.' So I made a deal — you ready for this? — $150 I got. ... I kept working with Dave for the rest of his life."

Listen to Taylor tell the whole story:

You brought Bob Dylan to Boston for his first concert in the city. How did that come about?

That happened because of relationships. … In the early days, [Newport Jazz Festival founder] George Wein was partners with Albert Grossman on the folk festival side of the Newport thing. And Albert Grossman of course was the manager of Bob Dylan, Peter, Paul & Mary, Gordon Lightfoot. When Albert decided he wanted to bring this young artist, Bob Dylan, into Boston to do a concert, he asked George, 'Who do you know in Boston?' George says, 'Well, Fred Taylor. Those guys can do the whole concert for you.' That's how it came to me. Albert Grossman to George Wein to me.

Tell me about Paul's Mall and the Jazz Workshop, which I understand were at the center of Boston's jazz scene at the time.

"[The Jazz Workshop's founder] said, 'You know, I'm going to be opening up the Jazz Workshop on Boylston Street, I'd like you to maybe come and manage it and book it for me.' ... He was transferring all his liquor licenses over to Boylston Street because the turnpike was being built, it was coming through and they were going to take all his property. So I started helping him book the Jazz Workshop. We took ownership in 1965 when Paul's Mall opened, and we took ownership of that about a year later."

"Virtually the history of jazz we booked in those years."

"At Paul's Mall I played comedy, big bands, R&B. I was probably one of the first to really start playing blues, with John Lee Hooker and Buddy Guy and Junior Wells and Big Mama Thornton and Muddy Waters — James Cotton. God, we did blues up and down."

"But the jazz scene [in the South End] was beginning to fade out. Clubs were closing. There weren't that many clubs going. Paul's Mall and the Jazz Workshop became the center of Boston's activity."

Advertisement

Tell me about when you brought Miles Davis to Boston in 1981.

"I'd heard rumors that Miles was in the Columbia studios in New York and was starting to get ready to record again. Then I got a call from Miles saying he wanted to come to warm up, because he was going to be doing a big reentry concert in New York."

"He had disappeared for about five years, and this was his first public appearance after five years of being incognito. And the first night we had press from all over the world. France, England, Belgium, Tokyo. Oh my God, it was unbelievable. I had a proclamation from the mayor. We did two shows a night for four nights — sold everything out."

But it was a risky proposition, bringing Miles Davis to town.

"Yeah, Miles was a very unpredictable person in those years. But I had a relationship with Miles. I was the only guy he would play for in Boston. I always was his start up. At Paul's Mall and the Jazz Workshop, every time he got a new band I would get the call: 'I got to come in.' We broke the Bitches Brew band at Paul's Mall. I just had this relationship with Miles that was sort of unspoken but very strong. In his book, in his autobiography, he mentions my name. Miles never talks about anybody, but he actually mentions my name."

Jazz has changed radically over your decades — and you've witnessed much of the history. What do you think about today's jazz scene?

"It's very mystifying. There are no new clubs. But there's a lot of small activity all over the suburbs. Restaurants have little trios playing. ... When you start going out into some of the restaurants you'll find there's a lot of real jazz going on, all around the Boston area, but not in Boston. [Nearly] all the hotels have done away with it, even piano bars are gone."

"Every high school has a jazz band. And all the colleges have jazz bands. But for some reason, the contemporaries of those people in the jazz bands don't come out to see them. There's tremendous jazz activity musician-wise, but not audience-wise. And I don't understand it, I don't know what the missing link is."

"Here is today's new vehicle: YouTube and the internet. You get lucky and you put a YouTube piece up that somehow gets traction and you suddenly have 50,000 viewers — now you're becoming an attraction. This is the new silver bullet."