Advertisement

Why Boston Has A Confederate Monument — And Why You Can't See It Right Now

Take a boat to Georges Island in Boston Harbor, and you'll see something you might not expect: a Confederate monument.

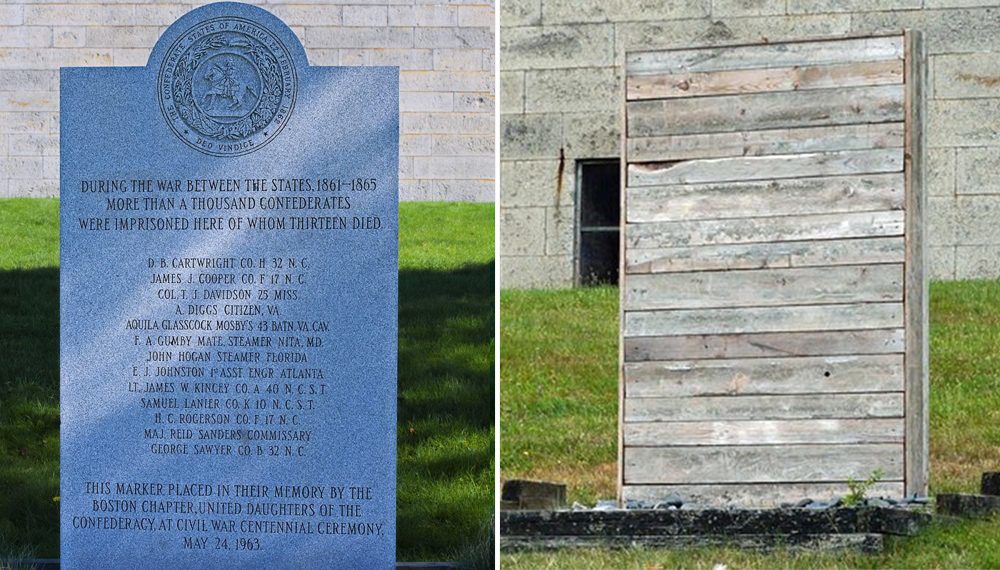

Actually, right now you won't see it. The stone, the only Confederate monument in Massachusetts, has been boarded up since June while the state figures out what to do with it — a question that has new urgency in the wake of last weekend's violence in Charlottesville.

The granite block, which sits outside Fort Warren on Georges Island, lists 13 Confederate soldiers who died there as prisoners.

Heather Cox Richardson, a Boston College history professor who has written extensively about the Civil War, says that makes it different from statues like the one of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee that sparked controversy, and then fatal violence, in Charlottesville.

"It is slightly different, I think, to have a memorial to prisoners of war than it is to have a memorial to Confederate generals," Richardson said Wednesday.

But that doesn't mean it will stay.

"That's kind of a very fine distinction that maybe is too fine for this present moment," Richardson said. "So my guess is this is going to be a clean sweep of all Confederate memorials."

But the location of the Georges Island marker also makes the question of whether to move it — or remove it entirely — a bit complicated, because Fort Warren is a national historic landmark as a Civil War-era military site. That means that any change to the site, which is managed by the Department of Conservation and Recreation, also requires approval from the Massachusetts Historical Commission, which is overseen by Secretary of State William Galvin.

Debra O'Malley, a spokeswoman for Galvin, said Wednesday that the historical commission informed DCR that the agency had to file a "Project Notification Form," or PNF, detailing any options DCR is considering and which ones it would prefer, how it would remove the monument (if it did) and how any changes would affect the site. She said the commission sent that form to DCR Commissioner Leo Roy on July 14 but has not yet received it back.

A spokesman for DCR said that the commission is responsible for the process. Galvin declined comment.

Gov. Charlie Baker issued a statement in June about the monument but has not commented further.

“Governor Baker believes we should refrain from the display of symbols, especially in our public parks, that do not support liberty and equality for the people of Massachusetts," said the June statement from communications director Lizzy Guyton. "Since this monument is located on a national historic landmark, the governor supports [DCR] working with the historical commission to explore relocation options.”

How It Got Here

But you may wonder how a Confederate memorial ended up on Georges Island in the first place. The answer involves another surprise: There was a Boston chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

The national Daughters organization still exists (and did not respond to a request for comment); the Boston chapter is now defunct, but it put up the memorial in 1963.

That puts it in line with many other Confederate memorials erected in the 1950s and '60s, as the civil rights movement gained momentum. Another earlier wave happened around the turn of the 19th century — and not, as you might assume, during Reconstruction right after the Civil War.

Confederate monuments didn't go up immediately, Richardson said, "because the South doesn't have two nickels to rub together" at the end of the war. Even Stone Mountain, one of the most controversial memorials, was dedicated not during Reconstruction but in 1970, she said — by Spiro Agnew, then vice president.

Communities across the nation are debating how to handle such sites. For her part, Richardson said, "I would deal with it on a monument-by-monument basis," perhaps keeping some as reminders of history, with ample context and explanation of their background, but removing others.

"Some can be contextualized," Richardson said, "and some simply have to come down."

A little context on the Georges Island monument: Its inscription refers to the "war between the states," a term for the Civil War used more often in the South, and features the Confederate motto "Deo Vindice."

As for the argument put forth by some — including President Trump on Tuesday — that removing Confederate statues is just the first step toward eliminating monuments to other historical figures, from Thomas Jefferson to George Washington — Richardson doesn't buy it.

"That argument is so stupid I even have a hard time grappling with it," she said. "The Confederates were fighting to destroy the country. The founding fathers were putting forth a group of expandable principles that we still, theoretically, live by. So that's just an absolute red herring, and it makes me crazy when people spout it."