Advertisement

After Helping Sharecroppers In The South, Eugene Richards Came Home To Boston's Busing Battles — Taking Photos That Launched His Career

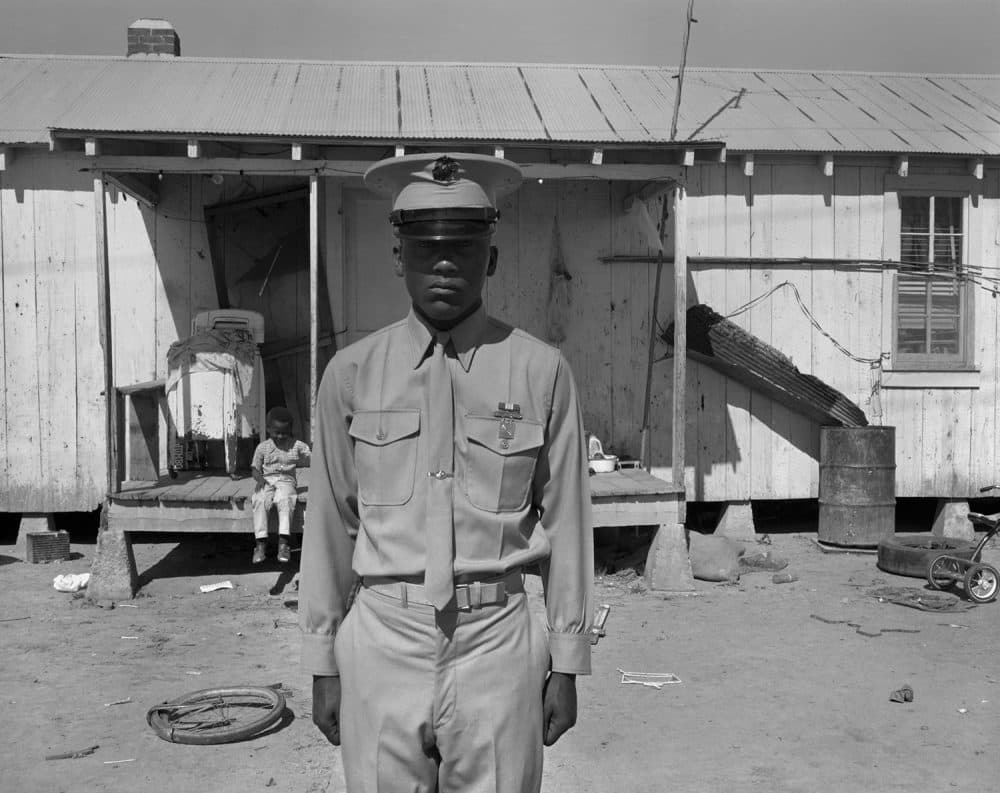

Eugene Richards had spent a few years in the Arkansas Delta, helping African-American sharecroppers caught between poverty and virulent racism. Then he returned to Boston in 1973 to find his city broiling with its own civil rights fight. People — especially in South Boston — were violently opposing a federal court order requiring the Boston Public Schools to desegregate by busing children to schools outside their neighborhoods.

Boston, he says, “is a very universally beloved ‘intellectual, artistic’ town and you wouldn’t expect this kind of s--- to be going on in Boston. You wouldn’t expect people to be throwing Coke bottles and bricks at buses full of kids in 1974, ’75. You just wouldn’t.”

Richards photographed what he witnessed in Arkansas and Boston, pictures that would launch his career as one of the great social documentarians of the era. The full span of his work is showcased in a book, “Eugene Richards: The Run-On of Time,” published this year in conjunction with what is billed as “the first museum retrospective” of his work, which debuted at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, this summer and travels to Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in December.

“I don’t have an idea necessarily that these pictures are going to change everything,” he says. “I just think people have to keep a historical record of the world that we’re living in, both good and bad.”

Obligations

“I think the factor that probably influenced my social concerns was the same one that influenced a lot of people my age, which was the Vietnam War,” Richards says.

He was born in Boston in 1944, a white kid growing up in a triple-decker on Julian Street in Dorchester, before the family moved to Quincy. He studied English at Northeastern University and photography with Minor White at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1967, in protest of the Vietnam War, he cut up his draft card and mailed the shreds back to Washington.

“I made the decision that I couldn’t go,” he says. “And it was a very, very, very difficult decision for me. One that had a lot of shame to it in some cases because people I knew were going. But it’s one that I took. And that, I think, began to shape a sense of responsibility. Because I felt after making the decision not to go … I felt that I still had an obligation.”

So he joined VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), one of President Lyndon Johnson’s "War on Poverty" programs, and moved to the Arkansas Delta in 1969 to help African-Americans there.

“I was assigned to the small town of Augusta, Arkansas,” Richards says. “I worked in daycare and did various kinds of social runs with people who had need. … The Delta at that time was among the poorest places in the country, exceedingly poor population of, in many cases, sharecropper families. I loved my town and I loved my work, but over a period of time things started to happen. I think people resented the outside person coming from Boston.”

One time, he says, “I was in a truck stop in the town of Wynne, Arkansas, a restaurant, stopping for a cup of coffee, and [a couple African-American colleagues] came in, naturally sat down. They were young women full of energy and they wanted something for themselves. And the man took a gun out from behind the counter and pushed us out of the restaurant.”

Another time, “Richards endured what may have been a brutal beating that knocked him unconscious, permanently erasing his memories of the incident,” according to “Eugene Richards: The Run-On of Time.” He woke in a mental hospital not knowing how he got there.

Not long after, the book says he was “terminated from VISTA [in 1970] after some agency authorities see his political activism, physical confrontations, and run-ins with police as a liability.”

'Photography I Care About'

Richards landed in nearby West Memphis, Arkansas. There, with some fellow former VISTA members, he founded Respect, Inc.

“We joined together to start this storefront and we distributed food and legal advice and carried people to doctors,” he says. “At the same time, in order to engender interest in the area and to try to raise money, I began to photograph more and more. I would go out onto the former plantations and became quite close to the sharecropper families that lived there. That was really my beginning both of the photography I care about, but also all my relationships in photography, which are to this day the primary reason I stay with it.”

He photographed farmers and cotton fields, church and prison, a wedding, a man with his face bandaged after an “assault by Klansmen,” the family of a black man shot dead by police and Mrs. Jackie Greer, a mayoral candidate wounded when police attacked a protest of school segregation. The photos would become his 1973 book, “Few Comforts or Surprises: The Arkansas Delta.”

“The bravery of the local citizens was amazing,” Richards says. The civil rights movement “was late to come to the Arkansas Delta because there was no support, there was no money, there was no budget the way of a classic civil rights movement, but the people were forming their own movements.”

Richards says, “My instances of violence were real, but they were small. One morning after [I got] out of church, a man cut me with a razor, cut my eyes up. I was very lucky not to lose my vision. Things like that would happen. People would turn the gas on at our house or take the wheel lugs off of my girlfriend’s car and that kind of thing. … But it was still shadow elements of what happened to the local population.”

Meanwhile, Resist was going broke and tensions were brewing among the group, so they ceased operations in 1972.

Dorchester Days

“The old neighborhood isn’t the same as it was,” Richards wrote in his 1978 book “Dorchester Days.” “It’s more run down, more foreboding, a brooding mix of old timers and immigrants, of working class aspirations and grinding poverty that everyone believes will explode someday.”

After crashing briefly at his parents’ home in Quincy, Richards moved back to his childhood neighborhood of Dorchester in 1973.

“When I had lived in Dorchester when I was a child, it was Irish, Italian, I think there was occasional Jewish kids,” Richards recalls. “I moved away for all these years. When I came back, it had changed totally. It was black, Puerto Rican, it was still Polish, people from the Caribbean, it was a real mishmash of people.”

And in South Boston, a couple miles from his place in Dorchester, Richards says, “There was a very strong, almost nationalist movement against school busing going on. That started to spread. … A match was lit.”

Richards was frustrated by his own struggles to find work, but "I had time to wander the streets" — and photograph.

In Dorchester, he documented families getting by in rundown apartments. He photographed a wedding, a first communion, church, fire, tears. He roamed South Boston, where the racism was scrawled across the walls. In one iconic photo, a kid jumps a bike over a makeshift ramp as a Dalmatian stares into camera. On a brick wall in the background, someone has scrawled "Kill N------!"

"You came from the South, people lived in the same town, they didn't like each other, but they worked side by side,” Richards says. “South Boston, you didn't go in there if you were the wrong color.”

In Boston, “you wouldn’t expect there to be ‘Kill N-----’ signs on the walls and swastikas all over the way,” Richards says. “Now, you might today because we’ve seen a resurgence of people painting swastikas, that kind of thing. But it was pretty shocking. I reacted to it with kind of dismay and began photographing that as well.”

The Boston photos became his book “Dorchester Days.” He left out the South Boston pictures when it was first published — "I was being defensive of my town,” he says — but added them to later editions.

“Dorchester Days,” he says, “ended up in the hands of people in New York who invited me to Magnum, into the agency, which was a major point of my life.” It prompted him to leave Boston and move to New York in 1982, where he continues to reside.

Magnum — "the granddaddy of photojournalism agencies," according to The New York Times — was formed as a collective by a renowned group of documentary photographers in the wake of World War II and continues to be one of the premier photojournalist groups all these years since.

Magnum, Richards says, “opened me up to the world of magazines. I started getting assignments and I found out that I could make a living, because I couldn’t in Boston at all. I never made what people call a good living. But you’re doing what you want to do, so life is pretty good. I started to get assignments to go places in the world. When I first became a member of Magnum, I’d never been out of the country. … My first assignment was to go to cover the war in Lebanon. You couldn’t have picked a less likely person or more inexperienced person. I went there and I found that I could function as a reporter there. It was all a learning experience. It was a pretty profound time that I could suddenly move forward in photography.”

He went on to photograph emergency rooms and drug dens, in the backs of police cars and desperate prisons and psychiatric hospitals, in so many struggling homes, at so many funerals. His intimate, gritty photos seem to call on us to face these difficulties frankly — and maybe do something to make things better.

“I want to realize how complicated things are, that they’re not nice and simple, conflict isn’t nice and simple, illness isn’t nice and simple,” Richards says. “Life isn’t always easy. … The adage of a person [working] in the emergency room is do we really want to do it -- they love their work -- but someone has to do it. This is not an analogy to me being a doctor, but that’s how I feel about the work: Someone has to do it.”