Advertisement

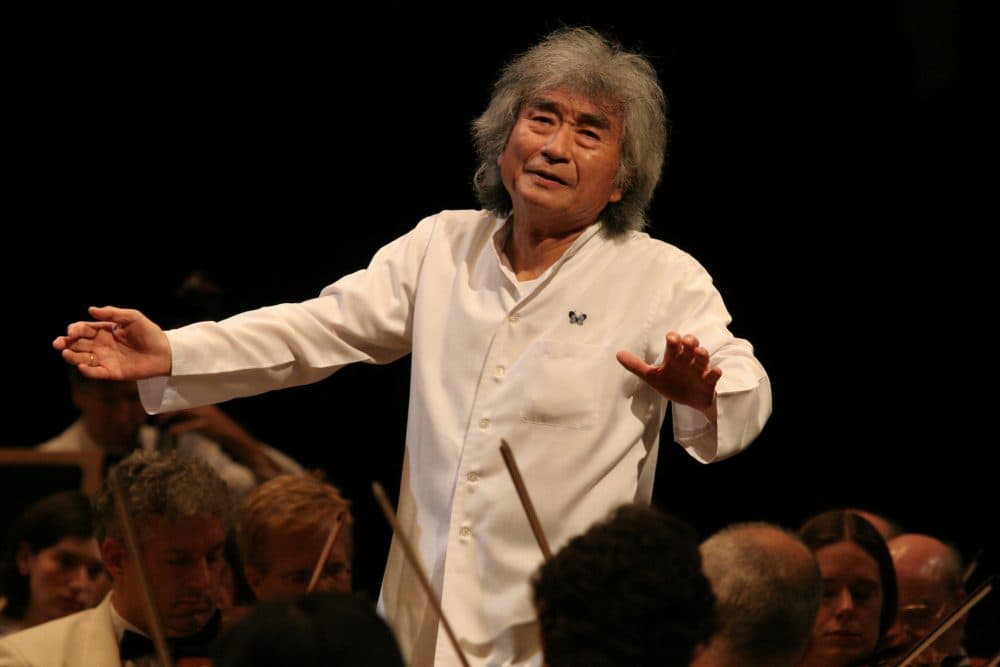

Longtime BSO Maestro Seiji Ozawa's Winding Road To Stardom In Japan

Resume

TOKYO — Twenty-nine years. That's how long Japanese conductor Seiji Ozawa led the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He started his record-breaking tenure as music director in 1973.

Ozawa means a lot to Boston, but back home in Japan, the now-82-year-old maestro is revered like a sports or rock star.

“When you when you walk around with Seiji Ozawa in Japan, it's like, you know, the heyday of Michael Jordan,” BSO managing director Mark Volpe told me backstage at Suntory Hall during the orchestra’s recent concert tour stop in Tokyo. “Seiji is obviously first and foremost a serious musician, but he's a celebrity here — on a par of anything that you would find in pop culture or sports in America.”

But Ozawa’s road to becoming an icon has been a rocky one filled with challenges — and stories.

More than half a century ago, Ozawa was a student at the renowned Toho Gakuen School of Music. That's where he met violinist Ikuko Mizuno, who now plays with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

“He was poor student and I was a student — we couldn't afford the ticket,” she recalled. “We tried to buy the cheapest one, and we couldn't. So we sneaked in, and we heard the BSO, and we said to each other, ‘Wouldn’t it be fantastic if we could play sitting in that orchestra?' " she said with a laugh. "Who knew that [would] happen?”

The BSO was one of the first Western orchestras Ozawa saw live on stage. He was born in 1935 and spent his early years in Japanese-occupied Manchuria. His family returned to Japan when he was 9 years old and struggled through the second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

“He was adamant that music was the only way to survive this kind of situation,” Mizuno said of Ozawa, “and he put energy into it.”

His perseverance would pay off.

In 1960, BSO music director Charles Munch — the same conductor who led the orchestra’s performance Mizuno and Ozawa snuck into — invited the young musician to what’s now the Tanglewood Music Center in the Berkshires.

Ozawa excelled as a conducting fellow and went on to study with Austrian maestro Herbert von Karajan in West Berlin.

He also caught the eye of the charismatic New York Philharmonic leader Leonard Bernstein who took Ozawa under his wing. Ozawa would go on to earn his stripes performing with orchestras in cities including San Francisco and Toronto.

But, Mizuno said, when he came home to conduct, Japanese audiences and musicians didn’t know what to make of the young, rising, eccentric, “flamboyant” musician.

"He was not well received in the beginning," she recalled. "I heard him say, when he left [the] second time to live in Toronto, he thought he burned the bridge to come back to Japan."

Ozawa’s attitude and style were new. “Everybody thought he was too Westernized,” Mizuno added.

Japanese music critic Hiroo Tojo remembered similar reactions. “Especially the older generation critics — they had a lot to say about Seiji because he was extremely different,” Tojo explained, through an interpreter. “So the older generation of critics really did not like that. But the younger generation critics really welcomed his presence.”

Tojo has been covering Ozawa’s career for decades. He says the maestro’s early approach to music-making was different than European or American conductors. Some have described the result as a “clear soup,” with each ingredient — or musical element’s flavor standing out. Tojo said it was especially apparent in the early years after Ozawa was hired by the BSO.

Tojo called Ozawa a “superstar that Japan created.” But when the BSO broke the white, European conductor mold by hiring him, it also carried deep, symbolic meaning on the other side of the globe, in a country devastated by WWII.

“In the history of the music scene — the classical scene here — that had never happened before,” Tojo said. “It almost meant that the darkness of the pre-war period that Japan had — it almost erased all of that because it was such a significant thing for a Japanese conductor to become a music director in the United States.”

Through the years, as Ozawa was busy conducting orchestras abroad, he also made it his mission to foster an appreciation for Western classical music at home.

He certainly has for the young fans who I met outside Tokyo's Suntory Hall a few weeks ago before a BSO rehearsal there.

When asked about who Ozawa is these days, 21-year-old Takuya Hiraoka paused for a second before calling him the “grandfather of the Japanese classical music world. I think he's now the most famous Japanese conductor.”

Ozawa is also known for founding the Saito Kinen Orchestra in Japan. It was named for his former teacher at the Toho school, Hideo Saito.

Thirty-one-year-old Naoko Kanazawa, who has been playing viola with Saito Kinen Orchestra for three years, says she really admires Ozawa.

“I really love Seiji Ozawa,” she said.

When asked why, she searched for words. Then, with some help, replied, “He has passion. He loves music.”

Kanazawa added that Ozawa has played a big part in her career. Like him, she's an alumni of the Toho school and has attended his workshops in Japan. Now she plays viola in the Nagoya Orchestra.

As for Ozawa’s status as a rock star? The young musician, through the interpreter, says she "feels like he’s above the clouds."

Among Ozawa's superpowers is his ability to internalize entire scores and conduct them from memory. But of course Ozawa is mortal.

In 2010 he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer and has been fighting it since. He wasn’t able to make the BSO’s recent Tokyo concerts conducted by current music director Andris Nelsons. Doctor's orders, it seems. His absence was felt by the fans, the BSO musicians and staff.

Managing director Mark Volpe is close friends with Ozawa and said he suspects the increasingly frail conductor would prefer to be seen — and remembered — as a force of energy.

“The body obviously has had better days,” Volpe said, “but the spirit is still there.”

Ozawa's prolific career and storied journey include far more paths, destinations, controversies and accomplishments — both inside and outside of Japan -- than could be summarized here.

Among his ongoing initiatives at home is the Seiji Ozawa Music Academy, founded in 2000, with the goal of promoting opera and nurturing young musicians in the form. And the conductor's importance and legacy as a cultural icon has been recognized by the Japanese government and the Emperor.

Correction: An earlier version of this post incorrectly identified who hired Ikuko Mizuno at the BSO. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on January 08, 2018.

This segment aired on January 8, 2018.