Advertisement

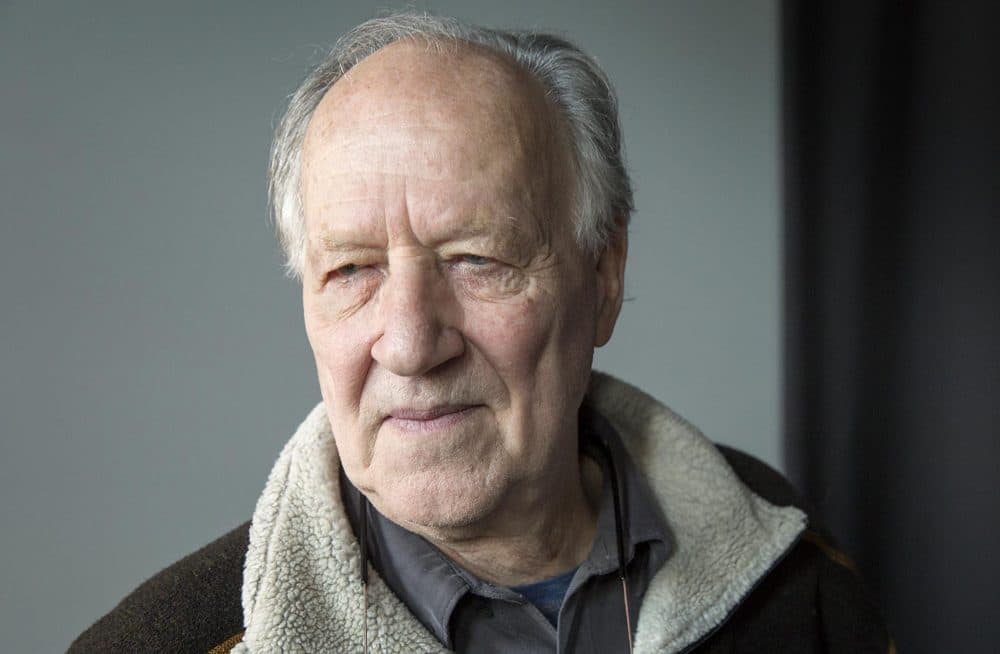

Hailing Herzog: Prolific German Filmmaker Receives Coolidge Corner Theatre Award

On Thursday, the Coolidge Corner Theatre honored the prolific, provocative German filmmaker Werner Herzog with its annual award for original and outstanding contributions to world cinema.

At 75 years old, Herzog has more than 60 documentaries and features under his belt. They include “Cave of Forgotten Dreams,” which gave us a rare glimpse into the world’s oldest paintings in France’s Chauvet Cave; his remake of F.W. Murnau’s classic, creepy 1922 silent film, “Nosferatu”; and his critically-acclaimed meditation on man vs. nature, “Grizzly Man.” The list goes on and on.

Herzog’s intrepid, philosophical approach to storytelling and immediately-recognizable style of narration are singular. His voice can be foreboding, gripping and comforting all at once. In "Grizzly Man," he poetically intones, “Treadwell is gone. The argument how wrong or how right he was disappears into a distance, into a fog. What remains is his footage.”

The globe-trotting filmmaker combed through hours of the self-shot videos Timothy Treadwell left behind after being killed by the wild Alaskan bears he dedicated his life to saving. "Grizzly Man" is just one example of how Herzog patiently investigates the human condition.

“Each film is more surprising and fantastic than his last,” the Coolidge's program manager Mark Anastasio said of Herzog. “He is attempting to ask and to answer some of these gigantic questions that we all have in life.”

Anastasio said Herzog has long been at the top of the Coolidge's list for the award, but “this was the first year that we took the chance of reaching out to him. And we got a positive response. The day that response came in, we all were jumping up and down with excitement.”

Previous winners of the Coolidge Award include Meryl Streep, Viggo Mortensen, director Jonathan Demme and film editor Thelma Schoonmaker.

The buzz was palpable at the theater on Thursday afternoon. Staff donned black T-shirts with the guest of honor's name emblazoned across the front.

Hours before the evening award ceremony, Herzog introduced himself to me as “Bavarian” and “a soldier of cinema.” He affably suggested I don’t play up the latter too much, saying, “I try to prevent being labelled as an artist in the academic sort of way.”

But if you’ve experienced his deep-dive documentaries you know “soldier” is actually fitting. Herzog brings audiences along on his extreme, often dangerous quests to far flung places -- a remote Antarctic research station, the steamy jungles of Brazil, indigenous Indonesian villages, death row in Texas, the birthplace of the internet in the “repulsive” (Herzog's word) corridors at UCLA.

For his 1982 film "Fitzcarraldo," Herzog notoriously directed his crew to haul a massive steamboat over a hill in the Amazon. He hypnotized the cast to make a film about a collective trance in Bavaria for "Heart of Glass" (1976).

Ecstatic human fantasies and follies are articulated to viewers through an alchemy of glorious imagery, surprising interviews, sublime music and Herzog's text, which he writes himself.

Throughout his recent Netflix documentary “Into the Inferno,” he and his cinematographer join equally passionate scientists to peer into the maw of blazing, burbling volcanoes.

“And of course they are one of the ultimate movie spectacles,” Herzog mused. “When you see a magma eruption, or an explosion, or the whole mountain coming apart, it is something which is very cinematic.”

It seems Herzog’s curiosity is insatiable. He sees it in his audiences as well.

"This kind of curiosity about what's going on underground," Herzog continued, "that if you drill deep under Boston, deep enough, you will hit heated magma that's flowing, and that wants to surge up and shift the continents and explode and will eventually take over one day."

Herzog’s enduring fascination with the medium of film is profound.

“That spell is always on me,” he said. “It's constantly on me all the time — this kind of spell — and the awe of looking at the world. It's always there. Cinema, deep inside, in its very nature, is something awesome.”

And that awesomeness has kept him going for decades.

“What I'm doing gives me great joy, and insight, and it's my connection to life itself,” Herzog said.

But the Coolidge's Herzog fest didn’t end with the award Thursday night. Fans and newcomers will have the opportunity to feast their eyes on a selection of the filmmaker’s works through March 14, including “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” and a midnight screening of “My Best Fiend,” Herzog’s intimate exploration of his fraught relationship with actor Klaus Kinski, his frequent collaborator and friend.

Herzog was excited to be in Boston, he said, and commented on the “magnificent” Coolidge Corner Theatre.

“But it's not just theater, it's the audience here — a loyal audience that would go and form a human chain around it.” (The community rallied to save the Art Deco theater in Brookline from being torn down in the 1980s.)

“That's what we need as filmmakers,” Herzog continued, adding with a smile, “it's the audience, stupid!” (echoing the phrase James Carville coined during former President Bill Clinton's campaign).

After all these years, Herzog doesn't have any regrets.

“I think I'm standing with what I've done,” he said confidently. “And if you gave me all my films -- and gave me millions of dollars if you could improve this or that film — I would refuse you. You stick to what you have created. It's the same with children. They have their own defects, like all of us. And if one of your children had a squint, or a stutter, or limp, you love them even more because they have that deficit.”

Among his many projects-in-progress is a documentary about former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. “I had two rounds of filming with him last year in October and early December. He wants to meet me again,” Herzog said. “I think he kind of likes me.”

Digital technology has enabled Herzog to surpass the output of his younger years. He released an impressive three films in 2016, but assured me he wasn't a workaholic.

So I asked what he does to unwind, and he simply responded: "I'm always unwound."