Advertisement

Commentary

Filmmaker Wim Wenders Isn't Afraid To Put It All On The Line

When I first started getting serious about films as a teen, Wim Wenders was one of the guys who defined arthouse cool. A master of the moody, existentialist road movie, Wenders won a lifetime pass from fans like me by giving the magnificently rumpled character actor Harry Dean Stanton his first (and second-to-last) leading role in his 1984 masterpiece "Paris, Texas." (The director himself will be presenting the film this weekend at the Harvard Film Archive, along with his almost-equally-great 1987 film, “Wings of Desire.”)

Hot on the heels of Werner Herzog’s February visit to the Coolidge Corner Theatre, I guess Boston is suddenly the happening place to meet septuagenarian titans of the New German Cinema movement.

In the late 1980s, pre-Tarantino era, we art-punk film fans skewed a lot more toward the Euro-centric. I’m just old enough to remember deadly serious dudes all dressed in black, smoking cigarettes in front of the long-gone Nickelodeon in Kenmore Square, talking up Wenders, Jim Jarmusch and David Lynch. These were the kind of guys who traded rare VHS tapes of obscure foreign films while listening to too much Tom Waits, and I desperately wanted to be like them when I grew up. (So mission accomplished, I suppose.)

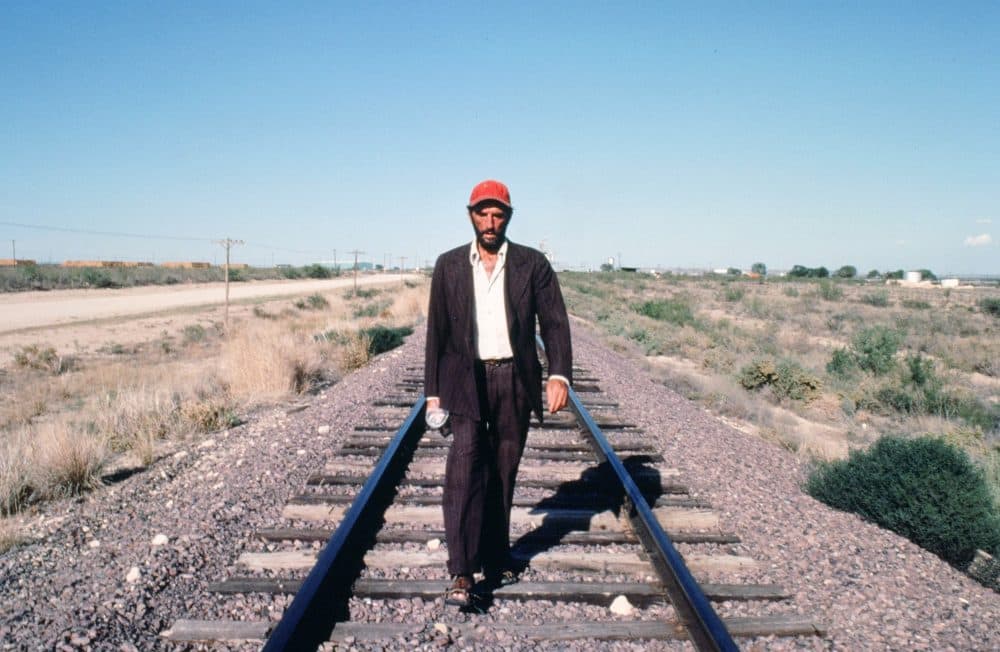

“Paris, Texas” is an almost impossibly perfect title for a film that filters Western iconography through the distinctly European lenses of Wenders and his brilliant cinematographer Robby Müller. Reportedly wrestled down from a gargantuan, unfinished screenplay by Sam Shepard (indie film guru L.M. Kit Carson gets a screen credit for “adaptation”) this boldly elemental film is like “The Searchers” with busted neon highway signs, full of magisterial landscapes as craggy as the face of its star.

Stanton plays Travis Henderson, who walks into the film mute and amnesiac after a mysterious, four-year sojourn in the desert. Taken in by his brother (Dean Stockwell) and reunited with his 8-year-old son (Hunter Carson, giving one of the greatest and most unaffected child performances in all of movies), Travis gradually begins to rejoin the world he so abruptly left behind, while we in the audience slowly start to piece together what happened that drove him away.

But anyone will tell you that the pièce de résistance of “Paris, Texas” is its astonishing 20-minute dialogue sequence during which Travis confronts his ex-wife (Nastassja Kinski) in a peepshow booth, speaking over the telephone while separated by a two-way mirror. It’s a remarkable piece of writing -- for all intents and purposes a Sam Shepard one-act play dropped into a movie -- with Wenders and Müller orchestrating the actors’ reflections in the glass to devastating effect. It’s impossible to imagine a contemporary filmmaker attempting such a scene today, and even harder to picture them pulling it off.

Three years after “Paris, Texas” won the Cannes Film Festival’s Palme d’Or, Wenders took home the fest’s Best Director prize for “Wings of Desire,” his achingly beautiful meditation on the then-divided city of Berlin, as seen through the eyes of an angel (Bruno Ganz) who longs to become human. Gorgeously shot in gauzy black-and-white, the film follows a couple of gentle, trench coat-clad ethereal beings as they hang out around town, eavesdropping on the thoughts of passersby and occasionally assisting in moments of grace. (Cinematographer Henri Alekan has claimed he conjured the film’s unique look by stretching one of his grandmother’s silk stockings over the camera lens.)

But when Ganz lays eyes on a spirited trapeze artist (Solveig Dommartin) he decides to forsake immortality and plummet to Earth, at long last seeing the world in warm, vivid colors. “Wings of Desire” is a lovely movie with a generous spirit best exemplified by the impishly delightful Peter Falk, playing himself as a fellow fallen angel, rambling on about how great it is to drink coffee and smoke cigarettes. The celestial premise is also eminently relatable, as who wouldn’t want to quit their job and run off to join the circus with Dommartin?

This sublime story got a howler of a Hollywood remake in 1998. The unintentionally hilarious “City of Angels” starred Nicolas Cage and Meg Ryan as our cosmic lovers, with the director of Steven Spielberg’s ill-fated “Casper the Friendly Ghost” reboot vulgarizing Wenders’ poetry in a rare Nic Cage movie that even *I* won’t make excuses for. (It does, however, feature a not unwelcome scene in which Meg Ryan gets run over by a truck.)

Anyhow, the film's legacy had already been tarnished a bit by 1993’s “Faraway, So Close!” in which Wenders attempted to explore the recently reunited Berlin by getting all our pals from “Wings of Desire” back together … to fight gangsters. Nastassja Kinski turns up as another angel, while Willem Dafoe plays a supernatural villain named Emit Flesti (aka Time Itself) and there’s even a scene where Falk pretends to be Lt. Columbo to confuse people watching him on a security monitor. Oh yeah, Mikhail Gorbachev is in it, too.

Notably absent from the HFA’s Wenders retrospective, “Faraway, So Close!” is a floundering muddle of a movie that will nonetheless always hold a special place in my heart because as a college freshman I managed to annoy Wenders, Lou Reed and Spalding Gray while trying to crash the premiere party at New York City’s Webster Hall.

Over the past couple decades the filmmaker has found great success with musical and performance documentaries like 1999’s “Buena Vista Social Club” and his 2011 3D extravaganza, “Pina.” But truth be told, Wenders never really got his narrative sea-legs back after 1991’s disastrous “Until the End of the World.” Shot in 15 cities in eight countries on four continents, his backbreakingly ambitious attempt at making “the ultimate road movie” was hacked in half by distributors and barely released in a spectacularly incoherent, 157-minute edit disowned by the director.

The HFA’s series closes out next month with a free screening of Wenders’ preferred 295-minute cut of “Until the End of the World,” which I saw at the Brattle a couple of years ago and wish I could report was an unfairly maligned masterwork. A speculative science-fiction movie in which people presciently become addicted to staring at handheld digital devices all day, it’s still a great big cluttered jumble of semi-realized ideas, but one that flows a lot better at five hours than it did at two-and-a-half. The most annoying elements are also fairly front-loaded, so if you can make it to intermission you’ll have a much easier time in the second half. (Or it’s possible I was just suffering from Stockholm syndrome.)

Yet still, how many other filmmakers are out there taking swings as big as this? Even the worst Wim Wenders movies are bad in fascinating and original ways, and the more cookie-cutter corporate products I sit through the more grateful I am for foolhardy dreamers who put it all out there on the line the way he does. Heck, sometimes you even end up with movies like “Paris, Texas” or “Wings of Desire.”

Wim Wenders presents "Paris, Texas" at the Harvard Film Archive on Saturday, April 7, and "Wings of Desire" on Sunday, April 8. He then gives a Norton Lecture at Sanders Theatre in Cambridge on Monday, April 9 at 2 p.m.