Advertisement

Why Greater Boston Keeps Getting Stuck In Traffic

Greater Boston is the sixth-most-gridlock-plagued urban area in the country, and it's costing you a lot of time and money.

The average driver in the region spends 64 hours a year — a workweek-and-a-half — stuck in traffic. That's twice what it was in Boston just 30 years ago, adding about $1,400 a year to the average commuter's costs.

But in a way, that traffic is bad and getting worse is actually good news.

Snapshot: Boston Area Traffic:

- 64 hours -- the delay per peak auto commuter in 2014

- 30 gallons -- the increased per-commuter fuel consumption due to travel in congested conditions

- 154 million hours -- the total extra travel time for 2014 auto commuters

- 72 million gallons -- the total increased fuel consumption due to travel in congestion in 2014

- Source: 2015 Urban Mobility Scorecard

Bill Eisele, a research engineer with the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, keeps track of urban traffic. He says an uptick in Boston's traffic congestion indicates the region's economy is mending from the disastrous 2008 downturn.

"Now the recession from congestion is over and we're sort of moving into this time where congestion is starting to come back up as we've seen a little bit more of the economic vitality," Eisele says.

Advertisement

Throughout Boston's long traffic history we've taken some surprising turns as we've tried building roads over, under, around and through the city.

And yet, we're still stuck in traffic.

Back When The Bottleneck Was On Purpose

Things began to stall nearly 400 years ago, at the scene of the city's first traffic choke point. Boston historian Jim Vrabel stands near East Berkeley and Washington Street, a site once called Boston Neck.

"It was the narrow strip of land that connected the Shawmut Peninsula to the mainland, and it was the only way in or out of Colonial Boston," Vrabel says. "It was a bottleneck and it was a bottleneck intentionally. It was chosen by the early European settlers for defensive purposes."

And to punish offenses. The road led out of Boston -- and for some -- to perdition, where crowds of rubber-necking Puritans blocked traffic to watch Quakers, witches and thieves hang at Boston's gallows.

"Thousands of people attended," Vrabel explains. "Another man executed for robbery was described as being launched into eternity here. So it was a pretty somber place."

Now, though, "there are a lot more ways to get in and out of Boston than there used to be," he says. "Back in the old days, this was the only place."

The single road at Boston Neck led to a network of footpaths worn into the wilderness over thousands of years.

Bryan Farr, an amateur highway historian, points to a map of a path going from Boston out to Springfield. The self-taught "roads scholar" says colonists found the native Pequot and Bay footpaths slow going.

"The first trip was in the late 1600s, and it took two weeks to get from Boston to New York City," Farr says.

British King George II was first to decide roads were needed to rule the Colonies. His government-funded road project widened 1,300 miles of footpaths for wagons and stagecoaches.

In 1751, Boston-born Deputy Postmaster Benjamin Franklin used a homemade odometer to measure distances along the King's Highway to determine rates for sending mail.

"He went through and measured with a bunch of surveyors every mile from New York City to Boston along this new Post Road," Farr says.

You can still see some of Franklin's milestones set along the upper Boston Post Road. Much of it would become Route 20.

From Roadways To Railroads (And Slow Streetcars)

"It all begins right here," Farr says in Kenmore Square, where Route 20 starts. "This was the main route to get out of Boston."

Farr, who's founder of the Historic US Route 20 Association, says the road is the nation's oldest and longest highway, stretching 3,365 miles west to Newport, Oregon -- a scenic, free ride across the country.

But Colonial capitalists thought there was money to be made in roadways. Route 9 began as the Worcester Turnpike in 1810 -- one of many private roads built during the "Golden Age of Turnpikes." But it was a financial failure; the four tollbooths were easily shunned, and travelers soon preferred the newly built Boston-to-Worcester railroad.

The new steam engine railroad technology, and a wave of new immigrants, transformed the nation's transportation landscape.

By the mid 1800s, Massachusetts had the most extensive network of railroads in the country, with Boston at the center. The word "commuter" was coined to describe passengers on the Dedham-to-Boston line who carried no luggage and therefore paid "commuted fares."

Boston got its first electric streetcar in 1888, and within two years, the Hub of the Universe was jammed with traffic. By one count, in a single hour 332 electric streetcars traveled along Tremont Street.

"The perception of traffic in the 1890s was that traffic was terrible," says Asha Weinstein Agrawal, professor of urban and regional planning at San Jose State University. She wrote her dissertation comparing the public's perception of Boston traffic in the 1890s and 1920s. Streetcars left a lot to be desired. They were loud, dangerous and slow. One commentator joked they should have sleeping and dining cars.

"You would hear people saying you could walk faster than you could travel in certain parts of the city on the streetcars," she says, laughing.

The public demanded that lawmakers address traffic congestion.

"The focus was really more on some kind of big construction project, basically to create physical space for traffic," she says.

Boston built space underground. The nation's first subway opened in 1897.

Two years later, South Station opened. It was the largest and soon the busiest train station in the world. North Station was second. At the peak, on board were nearly 70 million passengers a year.

Cars 'Strangling The City'

But Boston streets were rapidly being clogged with another kind of traffic — newfangled horseless carriages.

Stanley Steamers, made in Watertown, Duryea Motor Wagons and Rolls Royces from Springfield, and Fords mass produced in Cambridge clogged streets. There were no rules of the roads and streets were a mess. A study in 1892 found 90 percent were in poor condition.

Ryan Price, an editor with Chilton Automotive, says lawmakers again had to address the problem.

"And since they decided the traffic is going to get worse because the automobile is not going away and they're getting more and more and more of them, that they need to come up with a solution, " Price says.

And so in 1903 Massachusetts lawmakers created the automobile department. But it took one man's frustration and creative thinking to come up with a way to curb cars.

Henry Lee Higginson, founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, was sick and tired of drivers racing by his home at a blazing 15 miles an hour.

"He wanted to have knowledge of who was driving what cars so they could be brought to justice for speeding," Price says. "So he kinda used his influence to address the problem."

Higginson submitted a petition to register automobiles and Massachusetts became first state in the nation to issue license plates.

The fee: $2 a year. That first year there were 3,200 cars registered in the state. By 1922, Boston's planning board declared car traffic was "strangling the city." And by 1926, 140,000 vehicles were driving in and out of Boston a day. To reduce congestion the city issued its first parking ticket.

Once again the solution was construction. Road building boomed.

Work on the Central Artery began in the 1950s and was documented in a National Geographic special. The homes of thousands of Boston residents were demolished to make room for the road.

"The main feature of this so-called progress," the narrator in the National Geographic special said, "is an elevated six-lane expressway that rips its way through the heart of Boston."

Another person said in the special: "A structure like that was considered to be a sexy thing: Cars are up in the sky, people are down on the ground."

The '50s and '60s ushered in an era of optimism in technology. America's Technology Highway, Route 128, was constructed, and the Mass Pike was built to speed suburbanites into the city by day and out by night.

The postwar exodus to the burbs left Boston's population and economy in freefall. State officials came up with a traffic master plan, and again, the solution was more roads.

But this time, it was to reverse the flow of vehicles -- and fortunes.

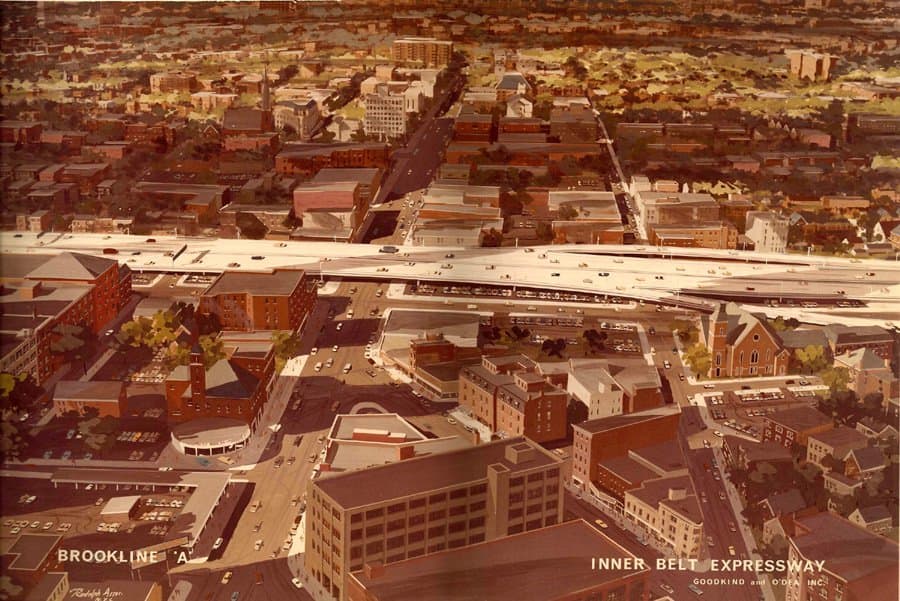

'The Inner Belt' And 'The Big Dig'

"It was actually devised to bring traffic into Boston," says historian Vrabel. "Boston was dying at the time and they thought if they brought more traffic in, they'd bring more business in. Plus the federal government was going to support it -- pay 90 percent of the cost."

The proposed road, dubbed "The Inner Belt," called for erecting an eight-lane highway, five stories above street level, looping through Somerville, Cambridge and Boston, connecting to the Southeast Expressway. At one point the raised roadway would have sliced between the Isabella Stewart Garner Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts.

"Eventually people howled and they were going to build it underground, but they were going to build it above ground through Roxbury and the South End and through all the other neighborhoods," Vrabel says.

Outraged activists took to the streets and the Inner Belt became the road not taken. Instead, in 1971, the federal highway funds went to improve Boston's subway system.

Mass transit ridership soared, but the Central Artery, driven through the heart of the city, was soon choking with traffic, carrying three times more vehicles than it was designed for.

Again, the State House solution to congestion: construction. But President Reagan repeatedly vetoed federal funding for the so-called "Big Dig." "The bill is a textbook example of special-interest, pork-barrel politics at work, and I have no choice but to veto it," Reagan said then.

"Reagan vetoing this thing was outrageous," says then-Massachusetts Secretary of Transportation Fred Salvucci. But Salvucci persevered, and Congress overrode the funding veto by a single vote.

Building the Big Dig took 15 years and was completed a decade ago. Final cost: $24 billion -- nearly half a million dollars an inch.

The massive project opened up the cityscape, reduced auto emissions into the air and traffic congestion, but quickly the added capacity attracted more drivers, pushing bottlenecks further into the suburbs.

Boston driver Kerwin Graham offers a familiar lament: "I think the Big Dig is a big disappointment. You know, there's more traffic, to me, yeah."

"Additional capacity is part of the solution but we can't just build our way out of congestion," says urban traffic expert Eisele. He says when it comes to roads, if you build it, they will come.

Today, during rush hour, it takes an average of about three times longer to get where you're going than at other hours of the day.

But if you think your traffic is bad, consider Don Burgess. As head of Boston's Traffic Management Center, he's been stuck in traffic for over four decades, trying to figure out ways to get things moving faster.

Burgess looks back to the future for a solution.

"You know, it's funny, you look back on some old traffic engineering manuals from the '40s and '50s, and the driver behavior, and the space between cars, and the acceleration, it hasn't changed that much," he says.

So if we're not going to change our driving behavior, and can't build our way out of congestion, in the future we'll need smarter roads and cars.

This segment aired on April 25, 2016.