Advertisement

Future Of Work

Demand For Senior Home Care Grows, But Its Pay Remains Low

Resume

This story is part of a BostonomiX series called “The Future Of Work” that examines the jobs of the future and the skills needed for those jobs.

If it's Thursday afternoon, you'll likely find Leroy Neuberg at Salon Maria in Brookline, greeting the stylists prepping for his regular appointment.

A bit of a trendsetter, Neuberg fancies his shoulder-length white locks braided: one slender braid on each side, and a fishtail down the back.

"I think it makes me look more sophisticated," Neuberg says. "It gives the impression that I'm tougher than I really am."

At 102 years old, it's hard to look tough, but Neuberg has the chutzpah to pull it off.

The Thursday hair appointment is just one of the many activities in Neuberg's busy week. He eats lunch daily at the senior center. On Tuesdays there's an exercise class and a movie. He recently attended a lecture on Lincoln's assassination, got a deep tissue massage, and enrolled in a poetry class. On Fridays, there's senior chorus, where this summer Neuberg belted out classics like, "Singin' in the Rain" and "Surrey With the Fringe on Top."

The woman responsible for keeping Leroy active and healthy — as well as doling out his medicines, accompanying him to doctor's appointments, and attending to his wounds — is his caregiver, Yamiley Jean Louis. She works for Neuberg from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m., Tuesdays through Fridays. Her job description is broad.

"I do everything for Leroy," she says. "I'm his housekeeper, caregiver, I'm his psychiatrist ... I'm his reader." Looking around at his tidy apartment in Brookline, Jean Louis adds: "This place was not like this when I got here ... it was very cluttered, things were everywhere, a little dirty, so I had to make it clean enough for me to enjoy it and for him to enjoy it as well."

But Jean Louis struggles to make ends meet. She's got student loans to pay off, and even though she earns $15 an hour -- a little higher than the national average -- she works a second job on weekends. At 43, she lives at home in Cambridge with her own aging parents.

Caregivers like Jean Louis who provide personal assistance and health care support are in high demand as more seniors live into their 80s, 90s and beyond. Many of them, like Neuberg, want to live at home, and out of institutions, for as long as possible.

Indeed, by 2050, the population of people over the age of 65 will nearly double, from 48 million to 88 million, according to PHI, a group that advocates for home care workers. Recruiting adequate numbers of home care workers to fill these jobs is becoming increasingly difficult, experts say. And it will only get worse, they add, unless salaries, training and potential for career advancement improves.

Paul Osterman -- an MIT economist and author of "Who Will Care for Us?" — says, "If nothing is done to improve these jobs, by the year 2040, there'll be a shortage of at least 350,000 paid caregivers — there could be more." (Even Osterman says this is a conservative estimate; PHI, for instance, reports the shortage could be more than 600,000 caregivers.)

Home care workers are typically women, and often people of color. With a median hourly wage nationally of just over $10 an hour and work that is often part time or part year, "one in four home care workers lives below the federal poverty line and over half rely on some form of public assistance," according to PHI.

But, Osterman says, there's potential to lift up the workforce by broadening the scope of home care jobs and providing more training.

"That will be good for the consumers they help but it will also be good for the medical system because it will save the medical system money," he says.

"If nothing is done to improve these jobs, by the year 2040, there'll be a shortage of at least 350,000 paid caregivers -- there could be more."

MIT economist Paul Osterman

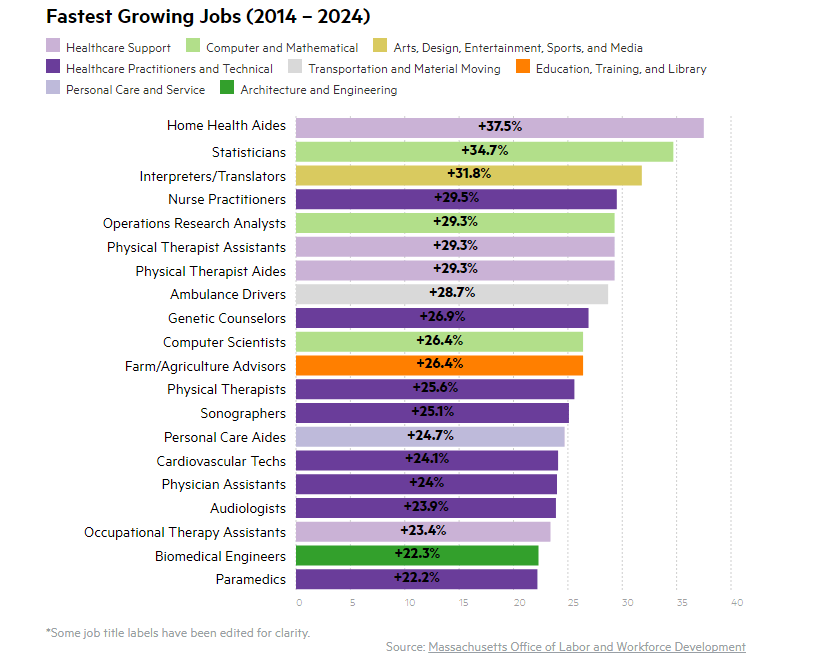

In Massachusetts, jobs for home health aides are projected to be the fastest growing occupation, increasing by more than 37 percent by 2024. Personal care assistants are also one of the fastest-growing jobs in the state.

But today, the home care industry is fragmented -- some aides work through agencies, some don’t; some are paid privately, others through Medicare or Medicaid; some are unionized, many are not.

“In general, a home health care worker makes considerably less than a golf caddie," says Jody Gastfriend, vice president of senior care at Care.com, an online marketplace that connects people looking for care with those offering caregiving services, including pet care, child care and senior care.

Gastfriend says that with the looming shortage of home care workers, the burden is increasingly falling on family members. And their employers are starting to take note.

"Employers lose an estimated $33 billion a year for senior care issues," she says. "People are not able to focus, they’re not able to show up, they’re distracted ... so all of a sudden dad needs to go to the doctor and you need to drop everything or there’s a crisis [and] you have to go to the hospital."

Jean Louis, Neuberg's caregiver, found her job through a Boston startup called Meetcaregivers. The company helps match families with highly vetted personal care assistants, home health aides and certified nursing assistants, and then pays these workers more than the national average.

Helen Adeosun, a former caregiver and graduate of Harvard's School of Education, co-founded CareAcademy nearly two years ago to support professional development for caregivers. The organization contracts with home care agencies to offer practical training through bite-sized "microcourses" online, like how to communicate with an Alzheimer's patient or how to bathe a senior.

Adeosun says her goal is to help build and enhance the career ladder for working caregivers. The idea, she says, is to take someone who is interested in a caregiving career and teach them skills over time.

"So they can go from someone who may never have been a caregiver to possibly being a home health aide, then a [certified nursing assistant] and then possibly a career in nursing," she says. "That whole trajectory, that whole pipeline is what we need right now as the number of people who are doing the work is shrinking."

Indeed, many families still struggle to find qualified caregivers.

Patricia Pucci, of Framingham, manages care for her 75-year-old mother, who has a rare form of dementia. Over the past five years, as her mother's health deteriorated, Pucci says she's seen numerous caregivers come and go, including "10 or 12" in the past year. Some show up late, she says, or not at all, or they just don't have the temperament for the job. Pucci says taking care of seniors requires patience and respect; it's not like a gig at Dunkin' Donuts or McDonald's.

"You're not pouring a cup of coffee or flipping a burger," Pucci says. "You are basically assisting a senior with their daily life and you should have compassion and you should have caring, and you should want to be there, not just because of the little money you're making, and I realize it's very little."

Lisa Gurgone, director of the Home Care Aide Council, an advocacy group in Massachusetts, says the organization recently launched new training courses for caregivers to help professionalize the workforce. One class addresses questions on seniors with mental health problems like depression and hoarding. Other courses deal with seniors and substance abuse; and LGBTQ seniors.

With this type of targeted education, Gurgone says, home care workers could become a key part of the larger health care team.

"These frontline workers are the eyes and ears of consumers in their home on a day to day basis," Gurgone says. "Research shows that when you get that worker there they will share information that’s important to the clinical team."

Jean Louis, who dreams of a career in medicine someday, says she loves her current job, but wishes home care workers, in general, got more respect.

"A lot of people try to put you down in this job," she says. "I used to work for a family where she would not allow me to go to the doctor's appointments with her husband. I would have to stand outside. She did not want me to be part of [that] world."

Leroy Neuberg credits Jean Louis for helping him live so well for so long.

We should all be so lucky, singing at 102, with a compassionate caregiver close by.

This segment aired on October 31, 2017.