Advertisement

Future of Work

When Algorithms Replace Post-Its: Artificial Intelligence Is Rewiring The Job Of A Lawyer

This story is part of a BostonomiX series called “The Future Of Work” that examines the jobs of the future and the skills needed for those jobs.

Shannon Capone Kirk runs the e-discovery practice at Ropes & Gray, a prestigious global law firm with panoramic views of the Boston skyline.

In order to understand what she does these days, she insists you need to understand what life was like when she entered the profession in the late '90s; her first job was "document review."

"What that meant was literally spending weeks upon weeks in either a warehouse or a conference room flipping through bankers boxes and reading documents, paper documents," said Kirk.

Back then, every large corporate law firm used an army of first-year law grads for this sort of paperwork.

"And if we found something that was relevant to the litigation we would tag it with Post-it notes, and that was it," said Kirk. "That is how archaic it was."

Document review was time-consuming and expensive but essential for the discovery phase of any legal trial.

The Software Revolution

In the early-to-mid 2000s, technology began to nibble away at certain legal tasks, as law firms experimented with software that could streamline this document review process.

Law firms would collect gigabytes of data, put it into a review platform, and then ask lawyers to run search terms.

Kirk says this system was advanced, but still "inefficient," and relied heavily on lawyers to sift through the results.

But in the last couple of years, e-discovery platforms, such as Relativity, have become more popular, and the algorithms they use have become much more sophisticated — they're no longer solely reliant on search terms. It's the machine learning how to prioritize what documents a lawyer finds — essentially, artificial intelligence.

Humans still set the parameters. But computers whittle down those millions of documents by using predictive coding. Kirk explains that predictive coding is essentially akin to the "thumbs up" button on Pandora — the lawyer trains the software to find what it's looking for.

Advertisement

Lawyers can now sift through gigabytes of data and find "300 key documents" within a week, according to Kirk. "Gone are the days when you would staff 50 to 75 first- and second-year associates to a document review, that just does not happen anymore," she said. "You could never do that before. Ever."

"A lot of this artificial intelligence work really affects corporate practice," said Frank Levy, co-author of the paper "Can Robots Be Lawyers" and a longtime MIT labor economist. But he's cautious about overstating the implications of automation.

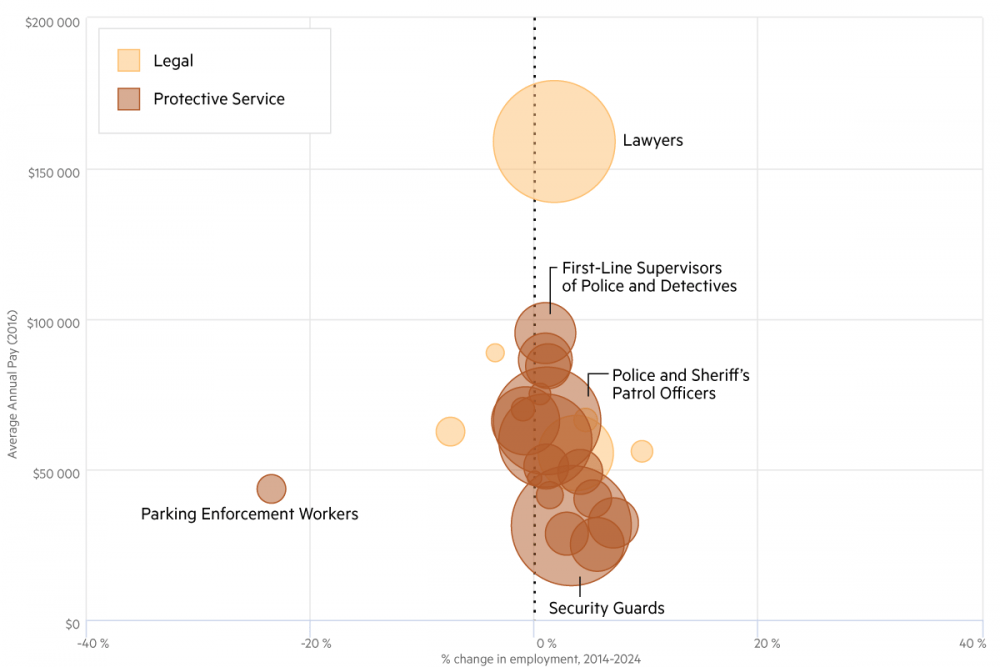

His research has found that current technology is replacing a relatively small percentage of a lawyer's total work, about 2 percent a year.

"A job is a bundle of different tasks, some of them can be automated, and some of them can't," Levy said. "There was a kind of implication ... that if you can automate one task within a job that everything else in the job is gonna be toast in about 20 minutes ... that's just really, totally untrue."

Still, he understands why lawyers are nervous: The legal labor market has tightened.

"In the last seven or eight years, [demand for legal services] has been pretty flat," said Levy. "And so that 2 percent a year really has some bite."

And, already, he said, you're seeing fewer people apply for law school.

From 2005 to 2015, law school applications across the country fell by roughly 40 percent, according to data from the American Bar Association.

A major reason law firms aren't hiring as many graduates as they once did is because of technology, but it's not the whole story.

"Part of it is the technology, but the other part of it is the fact that the industry now has numerous options for contract attorneys and outsourcing," said Kirk.

Life As A Contract Attorney

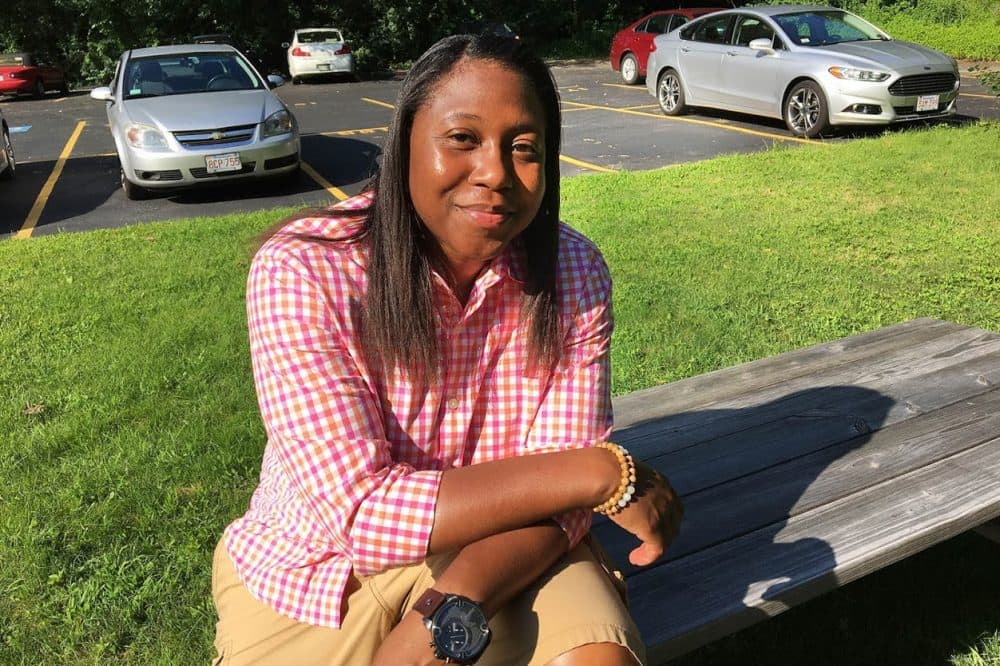

When Kellie Tiller, 34, graduated from the Massachusetts School of Law, a small freestanding law school in Andover, she started studying for the bar exam and picked up a job in retail.

"It was a little difficult finding a job at that time," said Tiller.

But once she earned her credentials, she began working as a contract attorney with the Beacon Hill Staffing Group.

"That’s what was available for the time being," said Tiller. "As we know, residual bills — they don’t stop because we aren’t employed."

For the past couple of years, Tiller has worked on-and-off as a contract attorney doing e-discovery.

"It requires a very special set of skills regarding patience," she explained, near the end of the day after a recent job at a nondescript building in Woburn. "Just your tolerance for being able to sit and continuously look at a computer screen where ... you feel like you’ve seen the same two or three sentences over and over and over again."

Tiller was paid less than $30 an hour for the job. A law firm attorney would have charged a couple hundred dollars for the same work.

"Technology is here to enhance, it's not here to harm necessarily."

Attorney Kellie Tiller

Tiller, a former semi-professional basketball player, still has the optimism of an athlete when she talks about her career. She admits contract attorney work using software to sift through online documents was not what she had envisioned for herself when she decided to go to law school. But when she graduated, she had student loans and needed a job.

"You just have to be able to go with the flow as it comes to you," said Tiller. "For me,

[this was] an opportunity to break into the legal profession."

From Tiller's perspective, e-discovery tools have made it easier for attorneys to sift through information very quickly; she said technology shouldn't be intimidating, particularly when it's making her job "efficient."

"Technology is here to enhance, it's not here to harm necessarily," she said.

And in any case, she's left the world of contract e-discovery jobs. Last month, she started a new gig as a public defender, working in the Lawrence District Court.

Tiller's career trajectory supports a theory people often mention as a possible silver lining to this shifting job market — the idea that as private law firm jobs dwindle, more lawyers may enter public service.

Teaching Law Students To Survive In An Automated World

Levy's research found that document review, the work that both Kirk and Tiller described, has largely disappeared from large corporate law firms — nowadays, lawyers at "tier one firms" only spend about 4 percent of their time doing document review, according to his review of invoice hours.

Legal work is changing because of two powerful, simultaneous trends: outsourcing and automation. It's that latter force — automation — that's rapidly evolving and not just in terms of document review, but also in terms of researching case history and analyzing contracts.

Gabe Teninbaum, a professor at Suffolk Law School, teaches a class called "Lawyering in the Age of Smart Machines" focused on teaching students how to create automated contracts (think Turbo Tax but for law).

"The same way that you or I might use software at the end of the year to fill out our taxes and create a tax return in just a few minutes for just a few dollars, we can do that with legal forms," said Teninbaum.

Teninbaum says the new frontier is automated contracts — which would allow lawyers to take on more cases for less money, and, in theory, make the law more affordable and accessible.

"There are some entire areas of law where basically the whole practice area could be automated," said Teninbaum. "Anytime there’s legal work that’s easily repeatable. In other words — wills, trusts, residential real estate closings. It's work that's done over and over and over again."

And Teninbaum says he's already seeing this evolution through companies like LegalZoom, the legal tech company that charges a fraction of what a traditional law practice would for a service such as drafting a will. (Note: LegalZoom is a financial underwriter of public radio.)

"Overtime, you’ll see continued sort of erosion of traditional legal jobs with technical jobs," said Teninbaum.

And, in his view, these more technical jobs will replace old-school attorneys.

Still, Teninbaum doesn't think we're anywhere near the death of lawyering. He says tech is merely changing an industry that, for years, was insulated from change.

This article was originally published on November 01, 2017.

This segment aired on November 1, 2017.