Advertisement

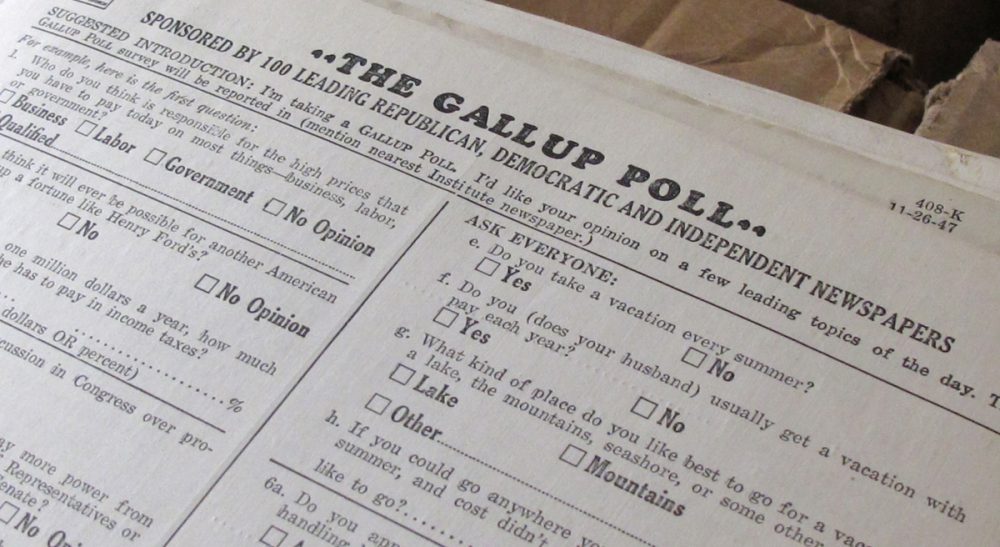

The Sad State Of Public Opinion Polling

If Mark Twain were a public opinion pollster today, here’s how he might sum up Americans and their grasp of the facts: “It’s not only what they don’t know that gets ’em into trouble, it’s what they know for sure that just ain’t so.”

“Democracy and Political Ignorance” and “Just How Stupid Are We?” are two recent books whose titles hint at the scope of the problem. Quizzing Americans about their country, past and present, has become a gold mine for TV’s late-night comics. (Jay Leno to woman on the street: “Name the ship the Pilgrims sailed to America on. The ship has the same name as a famous moving company.” Answer: “U-Haul?”)

Americans have a badly skewed impression of the nature and extent of their country’s generosity, priorities, and international image and comportment.

The laughs are good, but ultimately, the joke’s on us. To cite one example, when most Americans think that foreign aid is 10 percent of the U.S. federal budget (it’s actually about 1 percent), and don’t know that defense is the single largest budget item (about 20 percent), that suggests that Americans have a badly skewed impression of the nature and extent of their country’s generosity, priorities, and international image and comportment.

Closer to home, consider a 2011 nationwide study by Michael Norton of Harvard Business School and Dan Ariely of Duke University (based on income analysis by Edward Wolff of New York University). Asked to estimate their society’s wealth distribution, a broad spectrum of 5,000 Americans believed, on average, that the richest 20 percent owned 59 percent of the wealth, when in reality the top quintile owns 84 percent. Respondents also believed that the poorest 40 percent controlled 10 percent of the wealth, when in fact the poorest control close to zero percent.

Then the Norton/Ariely survey did something interesting: after respondents had given their answers, they were told the correct numbers and asked what they considered ideal income distribution. Americans of all stripes and persuasions said that the richest 20 percent should have only 32 percent of the wealth, a scenario that in the real world most resembles Sweden, the socialist bogeyman of so many American nightmares. This begs the question: When we are so uninformed about the realities of our society, how can fair and effective public policy be made?

To that end, and building on Norton /Ariely’s follow-up questioning, here’s a modest proposal. Why not make a simple add-on to opinion polls so that they might educate us as well as just hold up a mirror to what we believe (no matter how much of what we believe just ain’t so)? Respondents could be asked a few factual questions about the public policy issue (e.g. environment, immigration, health care) about which they are being polled. Those with a perfect or high score on this quiz could be dubbed the “Smart Set” and their responses to the poll’s questions highlighted as a sidebar to the poll’s overall results. Then I, as a citizen, could compare my opinions to those of the respondents who are demonstrably knowledgeable about the issue. If we differed on some aspect, I might say to myself, “Gee, maybe I should learn more about that question; maybe I don’t know all the facts.”

Traditional polling might even have a deleterious effect. Because we credit “the wisdom of crowds,” because opinion polling is presented as scientifically conducted, and because poll results are legitimized by respectful treatment in the media, polls lend unwarranted authority to what are only people’s opinions. Opinions, after all, are merely attitudes and beliefs, often formed on the basis of inadequate or incorrect information.

If polling were 'smart,' it might just help us fashion a better society...

For the many academic and nonprofit institutions engaged in polling, adding a “smart set” to their surveys would support their mission to educate. In a crowded field of pollsters and polls, a “smart poll” would also create a competitive advantage by drawing heightened interest to its results. Such polling could not only plumb opinion but could also act as a tool to spur the citizenry to become curious and better informed, thus leading to sounder thinking about issues facing society.

Our opinions shape our votes, and it’s our votes — and the demands we make on our legislators — that truly shape our economy, our country, and our democracy. If polling were “smart,” it might just help us fashion a better society, more like the one that prompted those brave folks aboard the original U-Haul to move to these shores in the first place.