Advertisement

Pete Seeger's Radical Simplicity

For some musicians, there was never a time before. None, at least, that can be remembered. They picked up a violin, sat down at a piano or drum set in the tender first years of life, and they never looked back.

It wasn’t that way for me. I barely even listened to music until college; I can’t tell you what was popular when I was in high school. Christina Aguilera?

Even after I got into folk and country and bluegrass music, it seemed like playing or singing it was well beyond my reach. When my friends jammed together, they would communicate in an incomprehensible language of gesture, jargon, and magic. I figured it would always be that way.

What he did want, though, from his own music, was to break down the barrier between professional and amateur, performer and audience.

Until I didn’t. One day, about five and a half years ago, I decided I’d had enough of watching everyone else have fun. I would at least give it a try.

This is what Pete Seeger urged. He wanted everyone to sing and to play, and he wanted to make it easy.

Since his death on Monday, we have heard a lot about his activism, and to the extent that obituaries and tributes have attended to his music, they have emphasized his topical songwriting and his performances on behalf of political causes. This is only fair. In his lyrics, protests, and testimonies, he projected political commitments.

But for Pete Seeger music was not just a vehicle for his message. It was his message. The simplicity of his sound was the foundation of his radicalism. Through the craft and dissemination of music that anyone could learn, he sought the ultimate democratic ideal: the erasure of all boundaries to participation.

While popular music was becoming more heavily produced, more spectacular, and more demanding of instrumental skill, Seeger insisted on a sound that was accessible not only for listening but for performance. In an age when recording technology grew as a creative tool, for Seeger, recording remained stenographic: the music came from voices and instruments, not from tracking, distortion, and overdubs. In his own songs and through the music he championed in his publications and on his television show “Rainbow Quest,” he defied the culture of virtuosity that celebrates prodigies and ever-mounting complexity.

Advertisement

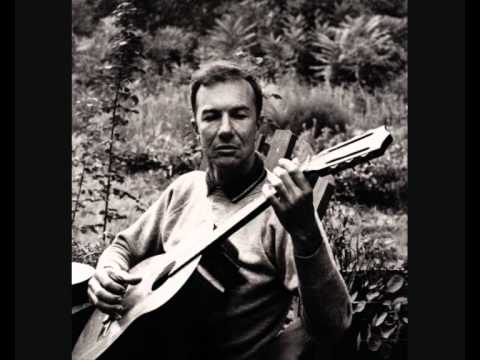

It’s not that he sought to do away with these other features of the musical landscape — he couldn’t have, and who would want to anyway? Virtuosity is exciting and inspiring. Nor did he pursue straightforward songs in order to mask a lack of musical proficiency. There were always stronger players, but Seeger had chops and compositional talent, as he demonstrated on original instrumentals such as “Living in the Country:”

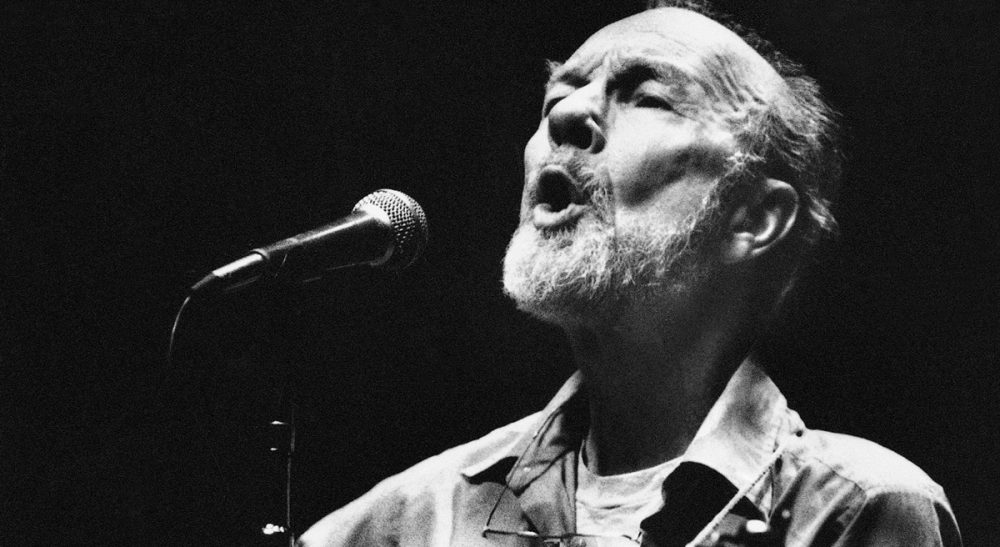

What he did want, though, from his own music, was to break down the barrier between professional and amateur, performer and audience. Thus he routinely called upon listeners to join him in song. Many of his pieces contained only three chords, and he performed them with few, if any, vocal embellishments. What he seemed to be saying, what he did say, was “even if you’ve never heard this song before, you can sing it with me.”

This dedication to universal membership and ability, above all, made his music folk music. Whether his songs truly were vernacular is always a matter of debate. What revivalists called “traditional” music was whatever folklorists happened to record on their trips to Appalachia and the South. Some of those songs were older than anyone could remember, but others were contemporary works, heavily influenced by the commercial music of the first half of the 20th century.

Yet even if his songs didn’t all originate with “the people,” Seeger made sure they ended up that way. His songs were going to be everyone’s songs, equally, and the music itself would convey this in its ease and accessibility.

He pressed this agenda even against his allies, some of whom were perhaps more interested in telling what they saw as the story of America than in enabling Americans to tell it for themselves. When Alan Lomax, the great archivist and revivalist for whom Seeger once worked, returned to the United States in 1958 after nearly a decade in Europe recording songs and avoiding Stateside red baiters, Seeger met him with both welcome and warning. Folk music, Seeger announced, was not Lomax’s or anyone else’s to define. “The folksong revival did grow,” he wrote in his magazine “Sing Out!” It “flourishes now like a happy weed, quite out of control of any person or party, right or left, purist or hybridist.”

There is a certain irony in Seeger’s promotion of amateurism and common participation. He was himself a consummate professional, ambitious and feverishly organized. But every populist movement has leaders, who invariably embody this contradiction.

Seeger never made much of his celebrity, but it had its uses. When he got on stage, the people came, and they sang with him. Ordinary listeners became musicians in his presence and with the help of his educational manuals and recordings.

If you’ve ever wondered whether you can do it, too, the answer is that you can. For what it’s worth, five-plus years later, I’m still going strong. You may never be the best or anything close to it — I certainly won’t be — but you can take part. This is the radical hope invested in Seeger’s simple music: at least in this one sphere of life, no one is denied entry.

Related: