Advertisement

Tsarnaev Trial Will Test What It Means To Be 'Boston Strong'

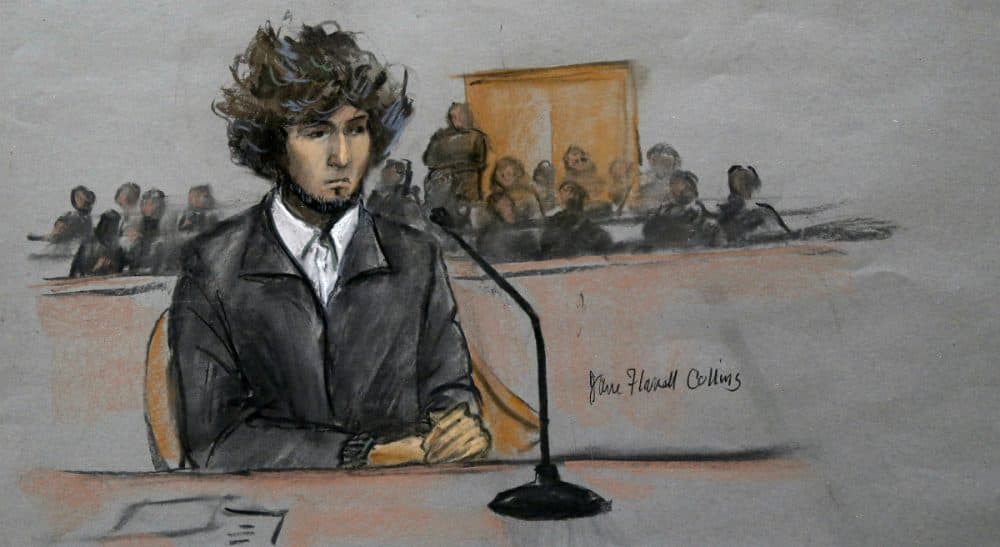

A 2-1 decision by a panel of federal appeals court judges on Saturday, denying a petition by defense attorneys to move or postpone the trial of alleged Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, means that jury selection will begin on Monday.

The process that led to this — described as “rushed and frenetic” in one judge’s dissent — also guarantees that serious due process concerns will keep this death penalty case alive on appeal and in the public eye for years and years to come.

It didn’t have to come to this. The government, represented by U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder and U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts Carmen Ortiz, have the option of proffering a plea agreement to Tsarnaev, namely, life without the possibility of parole in exchange for a guilty plea and no option to appeal. That would mean the case was over. Tsarnaev would be locked away, out of state, out of sight, for life. The media frenzy would end. All appeals would be foreclosed. Our collective focus could be on healing and support for the survivors and their families, and building for the positive future of our community.

The trial will be about us -- about the kind of society in which we want to live, and whether we will be ruled by our fears or by our values.

Instead, the federal prosecutors chose to press forward with a death penalty trial. One can imagine various reasons for that decision. It’s a historic and high-profile case. A trial supports Holder’s position that federal civilian courts are capable of handling terrorism cases much better than Guantanamo’s loathsome military commissions. A death penalty trial will enable Ortiz and her prosecution team to tap into the calls for vengeance from a Boston community that remains traumatized by the attacks. It will feel like payback time.

But vengeance is not justice, as I've argued here before. In reality, this trial won’t really be about Tsarnaev’s guilt or innocence: the evidence against him is overwhelming. The trial will be about us — about the kind of society in which we want to live, and whether we will be ruled by our fears or by our values.

“Due process” is a confusing term for most people, including lawyers and judges. Basically, it means that a trial must be fundamentally fair. In the United States and under our Constitution, in theory anyway, when the stakes are life and death, a defendant is due — that is, entitled to — the full protection of his rights to fairness in the judicial process.

A key element of due process is a fair and impartial jury. Without one, there cannot be a fair and impartial trial. That’s why the defense team filed repeated motions asking to move the trial out of Massachusetts. They wanted to guard against a jury pool tainted by widespread media coverage and hatred of Tsarnaev. They cited a similar case, the 1995 bombing of the Oklahoma federal building and courthouse by Timothy McVeigh, where the judge concluded that a fair trial could not take place in Oklahoma. That case, like this one, also involved a bomb that took the lives of children and traumatized an entire city.

Advertisement

Those motions from the Tsarnaev defense team were denied.

Another due process issue arises when federal prosecutors bring a death penalty case in a state where the voters have rejected the death penalty. The majority of people of Massachusetts are opposed to the death penalty. Yet, anyone who opposes the death penalty will be automatically excluded from the jury. What happens to the principle of the jurors representing a fair cross-section of the community? Most people would think that is part of due process, and it likely will be an issue on appeal.

The right to a defense means the time to prepare a defense. It doesn’t mean having a lawyer who hasn’t had a chance to read the documents. It’s like being asked to take a high stakes test without having been allowed to read or study any of the course material. And in this test, where the stakes couldn’t be higher, that right is being denied.

Tsarnaev’s defense lawyers are highly regarded lawyers. They filed a motion on Dec. 1 requesting more time to prepare. If they say they haven’t had a chance to read the 10,000 newly turned-over pages, and to analyze just-now-turned-over computer embedded data (for example, the hard drive from a computer owned by Ibragim Todashev, a Tsarnaev friend shot to death by an FBI agent in Florida in 2013), they haven’t. Again, their motion was denied.

Such failures also forever taint the trial, making what could be a display of justice instead look like a rush to execution.

In an impassioned dissent, First Circuit Appeals Court Judge Juan R. Torruella warned of the dangers of moving forward to trial in the face of these serious due process concerns. He correctly described the case as “one of profound importance not only for Tsarnaev but also for the people of Boston and for all of us who cherish the guarantee of constitutional rights for all litigants before this Court.”

Then he criticized his fellow judges for rushing to judgment. “Due to the artificial time constraints placed upon us, it is impossible to do more than take this quick glance” at the court filings, Torruella wrote. “Such a rushed and frenetic process is the antithesis of due process.”

Failures of due process create substantial issues for appeal, so we’ll be reliving this case on appeal for years to come, delaying the healing process. Such failures also forever taint the trial, making what could be a display of justice instead look like a rush to execution.

Choosing instead to defend due process -- to insist on it, even in difficult, emotional cases — demonstrates our steadfast allegiance to American justice and values, and defies anyone who thinks that violence can undermine our commitment to principles of fundamental fairness. That’s what it means to be Boston strong.