Advertisement

Is Football Acceptable In A 21st Century Society?

Under gray skies, inside Harvard’s historic stadium, I jog alone around the football field. The massive concrete oval is totally deserted. Passing the stadium’s south portal where a plaque from 1904 extols “the joy of manly contest,” I can almost hear the roar of a huge, invisible crowd, as though ghosts from decades past have never quite left the premises.

My grandfather is surely among those spectral onlookers. On Harvard’s 19th century playing fields, he took part in the first-ever “flying wedge” and captained the team for the 1894 Harvard-Yale “Springfield Massacre” in football’s bloody and unprotected early days. Perhaps not coincidentally, based on what medical science now knows, he would die before his time.

In the end, no matter how you parse it, to varying degrees we’re all complicit in the game’s collateral damage.

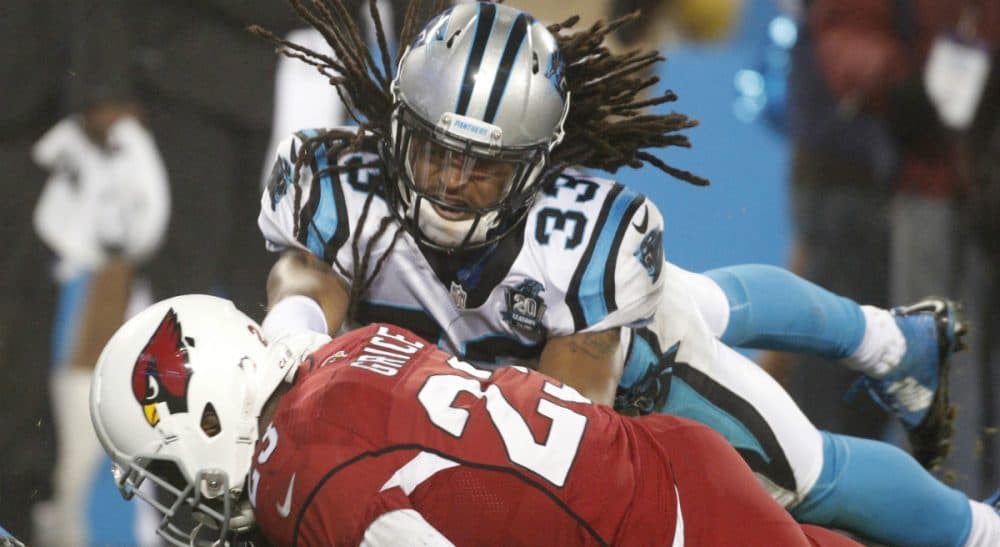

Against the backdrop of this year’s NFL playoffs, “the joy of manly contest” has become ever more bittersweet, as public opinion and medical research increasingly raise questions as to whether football’s toll on the human body and brain is acceptable in a 21st century society. Battle-scarred and limping to their seats, the NFL’s 20,000 surviving former players would, as it happens, fill much of Harvard Stadium. But they too are invisible, their lives after football ghostly and unseen.

After careers averaging about four years, eight out of 10 former NFL players report being in pain every day. NFL health benefits are limited, and many ex-players don’t qualify for pensions, which are inaccessible anyway until years after careers end. Both Sports Illustrated and ESPN have asserted that many former players, perhaps even a majority, experience bankruptcy or financial difficulties shortly after they stop playing. Younger ex-players live in poverty at the same rate as the general population, according to an excellent new book, "Is There Life After Football? Surviving the NFL."

Some 50 percent of parents now don’t want their children to play football, according to a recent poll. I’m glad my son didn’t grow up playing the game, yet I’m one of those imperfect fans who is perfectly willing to watch other people’s sons pound each other on Sundays. We can rationalize that NFL players now understand football’s dangers and freely choose to accept them. But the reality is, many players leave college poorly educated, equipped only for football. For others, the game has been their life’s commitment, so how can we expect them to say no to its pinnacle?

All of us who are football fans aid and abet the beautiful, brutal show. But shouldn’t working people who make their living from employment in NFL goods and services get a pass? After all, for them it’s a livelihood. That said, maybe we fans, casual or rabid, deserve a pass, too, since we make nothing off the NFL. In the end, no matter how you parse it, to varying degrees we’re all complicit in the game’s collateral damage.

That, of course, includes the NFL’s team owners. Among the wealthiest people in our society, owning an NFL team is for them a family inheritance, an absorbing hobby or a vanity trophy, not an income-earning necessity. Artificially enabled by a semi-socialist business model, generous tax breaks and anti-trust exemptions, the NFL is a business sustained by the destruction of players’ minds, bodies and quality of life. Doesn’t that create a special moral hot seat for those occupying an owner’s chair? New York Giants Hall of Famer Harry Carson says he sold his ownership stake in an arena football team precisely because of that human toll. If players knowingly choose NFL careers, NFL owners knowingly choose to profit from what they know will happen to players during — and after — those careers.

Advertisement

To be sure, NFL franchises and their owners can bring pride, stature and unity to their cities. Many owners parlay their teams into vehicles for civic good and philanthropy, beyond NFL franchises’ role as job-creating and economic-development engines for their localities. Yet there are less-violent sports franchises and other alternatives that could serve those functions, too. Studies show that cultural organizations and activities can produce as much economic stimulus for a city as a sports team.

I’m glad my son didn’t grow up playing the game, yet I’m one of those imperfect fans who is perfectly willing to watch other people’s sons pound each other on Sundays.

At the very least, NFL owners need to provide more effective and comprehensive financial and health care plans for all their former players. Consider that, until the judge ruled the amount too small, this $10 billion league nearly settled a class-action concussion suit, involving 5,000 ex-players, for $765 million. Compare that to $325 million — what a single individual, Giancarlo Stanton of the Miami Marlins, receives for playing (non-contact) baseball.

Football, so deeply embedded in our culture and economy, may well survive even without reforms. But as society grows ever more ambivalent about the game’s unavoidable human damage, the idea that it’s somehow glamorous to reap enormous profits from such carnage will be revealed for what it is: an antiquated notion that belongs in a bygone era.

I’m thankful my son didn’t grow up playing football. I’m thankful, too, he didn’t grow up to be an NFL owner. The costs of both are just too great.