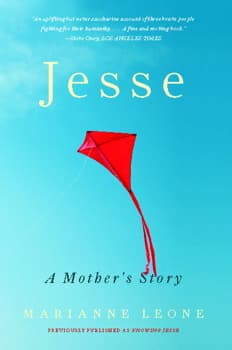

Advertisement

What Mother's Day Means When You Outlive Your Child

My mother loved oversized, sugary Mother’s Day cards with sentimental verses inside, rhyming couplets that somehow induced guilt and at the same time made your teeth ache. Every year I found myself resentfully pawing through pink paper tributes to motherhood at the card store, muttering under my breath.

Once I became a candidate for the once-a-year drippy card-and-flowers deal, I let my husband, Chris, know he was under absolutely no obligation — I wasn’t his mother, and our son Jesse was too young to get the idea behind the day. Maybe when he was four I could deliver a lecture about duped consumer victims to Jesse. And later, I could tell him that Mother’s Day began with Julia Ward Howe and a plea for peace, so that mothers wouldn’t lose their sons in never-ending wars. But Mother’s Day got inside Chris like an alien spore; some combination of surround sound advertising and free-floating pressure made him go to the store and buy stuff. When Jesse was still an infant I went into his room on Mother’s Day and found him in his crib cradling a card in one arm and scented soap in the other. Even though it wasn’t from Jesse, I enjoyed the soap. Later, in elementary school, I received teacher-directed cards from Jesse. Nice of them to think of me, but the teachers had written the cards.

Now that I’m no longer a mother, I can ignore Mother’s Day, but I’m haunted by words.

The teachers wrote the cards because our son had severe spastic quadriplegia, the result of a premature birth and a grade IV intraventricular hemorrhage on the third day of his life. He was also nonverbal, but cognitively intact. In fact, he tested in the 99th percentile, which made him much more intelligent than my husband and me.

But when Jesse mastered the computer, he wrote me quirky poems, which changed everything. My son gave me words, his words, words that were teased out of painstakingly drawn lists, then shaped into thoughts. Words I treasured because they were from Jesse.

Now that I’m no longer a mother, I can ignore Mother’s Day, but I’m haunted by words.

So on the day before my second ex-Mother’s Day, I got the word “Jesse” tattooed on the inside of my wrist, a semi-private part of my body that I can look at whenever I want. I’m looking at it now: an indelible filigreed reminder of loss.

Jesse wanted a tattoo. During the summer he was thirteen, we were invited to a backyard barbecue in our neighborhood. We usually saw Forrest, a tattoo artist who hosted the barbecue, or his girlfriend Rebecca on our daily walks to the marina. Our dogs played together, Goody dwarfed by their giant lab. Forrest was goateed and laconic, and Rebecca was a sunny blonde, a Vermont native as robust and healthy as the Vermont Maid picture on maple syrup bottles. At their barbecue, Chris, Jesse and I were the only unadorned people in a cluster of beautifully embellished skin. Jesse was agog, looking around with a slightly dazed, but blissful smile, as if he were spinning on a theme park ride. I asked him if he would like to get a tattoo and he responded with one of his most emphatic clicks. I told him he would have to wait until he was eighteen.

I got the tattoo the year Jesse would have been eighteen.

Chris and I climbed the steep stairs to Cobra Custom Tattoos, which was incongruously sited on the old-fashioned clapboard-fronted shops on Plymouth’s main thoroughfare. Forrest and Rebecca remembered us, though it had been years since they lived in our neighborhood. I told Forrest I wanted a tattoo for Jesse and he showed me a book of memorial tattoos, some of which were huge portraits of the dead meant to span a shoulder or cover a broken heart.

Forrest created a scripted version of Jesse’s name with an infinity symbol underneath on a piece of thin, parchment-like paper. It was simple, elegant and monochromatic black. I approved it — not realizing that the size he showed me was to scale — and he set to work after refusing any form of payment.

I wanted to flip off other people’s happiness with a flick of the wrist, fist raised, a power salute to death.

The skin is thin on the inside of the wrist, and it was painful getting the tattoo. I welcomed it. Jesse was gone. I wanted to be permanently marked and I wanted it to show.I wanted to flip off other people’s happiness with a flick of the wrist, fist raised, a power salute to death.

Chris, silently watching the ritual, had no such impulse. He honored mine, just the same. We’re still at the dance together, but he sat this one out. That’s okay. He never needed words as much as I did, and I need this word, this symbol of Jesse.

But now, after the rawness of the raised letters has healed, the red defiance has ebbed, and the word on the inside of my wrist is no longer an ashy lament. Today, the tattoo is an exuberant shout, a testimony to Jesse being in the world, an affirmation of his own wish to proclaim it, and a reminder that I was and will be his mother every day for the rest of my life.