Advertisement

The Spy Who Loved Me

At the end of my father’s life, he was raspy and small, forever lost in a storm of neurotransmitters backfiring from Parkinson’s disease. When he called me, the oldest of his three children, by his mother’s name, I grieved over the cold, hard reality that it was too late to ask him certain questions — questions that had been gnawing at me since my frequent childhood treasure hunts through his highboy to figure out who he was. Questions about my long-time suspicion that he had been a spy.

...the more I wrote about my father, the more I realized how little I knew him.

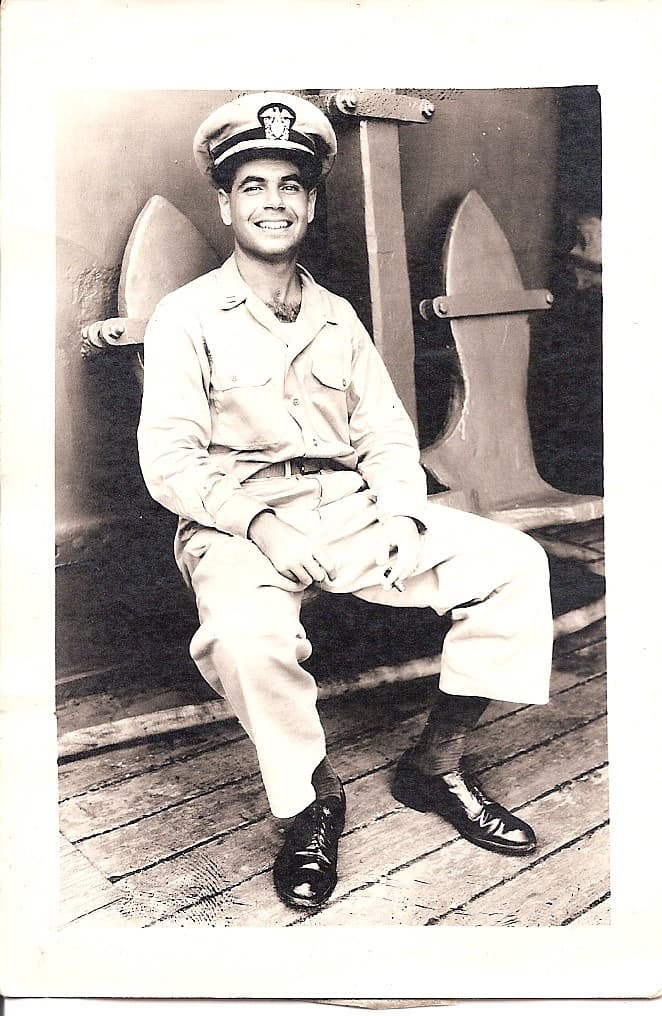

For years I tried to write my way to the truth by amassing anecdotes about my father the patriot, the man who was careful never to be a character in his own tales. There was the regimented father, the former naval officer, who marched my sister, brother and me around the house on the Fourth of July to the booming brass of John Philip Sousa. That was the father with his hand over his heart singing the Star Spangled Banner at his alma mater’s football games. There was also the picture of Dad as a young man — a scallop-edged photo in which he wears billowing khakis and a pith helmet; it was marked “Guatemala 1952.” I had found the picture in his sock drawer when I was 10. He grabbed it from me and issued his standard warning about curiosity and dead cats.

Yet the more I wrote about my father, the more I realized how little I knew him. Those who did were either dead or lost to me.

And then I remembered David.

My father had always called David a caballero, a gentleman. They had been the best of friends in business school, which Dad left before completing his post-war degree. David was from El Salvador, the son of a former ambassador, and served as the guide for my father’s frequent and lengthy travels in Latin America in the 1950s — trips that accounted for Dad’s American-shellacked Spanish. Trips that were said to be stints Dad did as an accountant for the United Fruit Company.

I tracked down David’s email address on a reunion roster for the Citadel, a military college. He responded to my email within the hour. He wrote in a blizzard of exclamation points: “Miracles do happen!!!!” He had been thinking of my father recently, he wrote, and it was as if he had willed me to find him.

Forty years after I discovered that photo of my father in Guatemala, I was in David’s no-frills pied-à-terre in midtown Manhattan, let in by his housekeeper. As I waited, I studied David’s family photographs, so familiar to me from the frequent Sunday visits we made to David and his family during my childhood. The pictures — so many of them — were crammed on a bookshelf in the living room.

When at last David appeared, I saw that he had aged into an amiable patrician.

I never really believed that curiosity could kill a cat. Curiosity was the path to clarity. It was power. My father’s naval records, which I obtained, gave him high marks for unwavering patriotism but revealed nothing more. A Freedom of Information Act request also yielded nothing.

So by the time I met David in New York, I had only my lifelong gut feeling that my father was hiding something from me, that, for an accountant from Connecticut, he had spent an awful lot of time in Latin America. That he was outgoing, yet elusive—almost as if he had already lived out his real life before I came along.

David was the only one left who could answer the question that no other source or authority had been willing or able to answer. I had come to ask if my father had been in the CIA. (The Agency itself, when I had asked, would “neither confirm nor deny” that my father had been in their ranks.)

David had been my father’s closest friend and ally in those years of secrecy and travel. He freely admitted to having worked for the CIA, first to help overthrow the Guatemalan government in 1952, and later to feel things out in Havana after Castro had come down from the Sierra Maestra Mountains.

...for an accountant from Connecticut, [my father] had spent an awful lot of time in Latin America.

Sitting beside David on his worn sofa, drinking a cup of coffee, I learned what I had always suspected. My father had worked alongside him. I thought of the photograph of my father in Guatemala.

“And after that?” I pressed. “What about after Cuba?”

David shrugged. “After that? Love.”

My father had fallen for the much younger Cuban woman who would become my mother.

Love had complicated his mission. Love for my mother, followed by love for me, the unplanned baby girl conceived on their honeymoon.

After that, there was the relatively quiet life of an accountant who tried to take his secrets to the grave. And then there is me, his daughter, who finally learned the truth about her father, the spy, but not in time to know him.