Advertisement

Could Cincinnati Be A Model For Police Reform Nationwide?

I believe there are three statements about policing with which no thoughtful person disagrees. First, it is a damnably difficult job, sometimes demanding life-or-death decisions made in seconds and exposing officers to the worst of humanity.

Second, the plunge in crime beginning in the 1990s was a national blessing and credit to police.

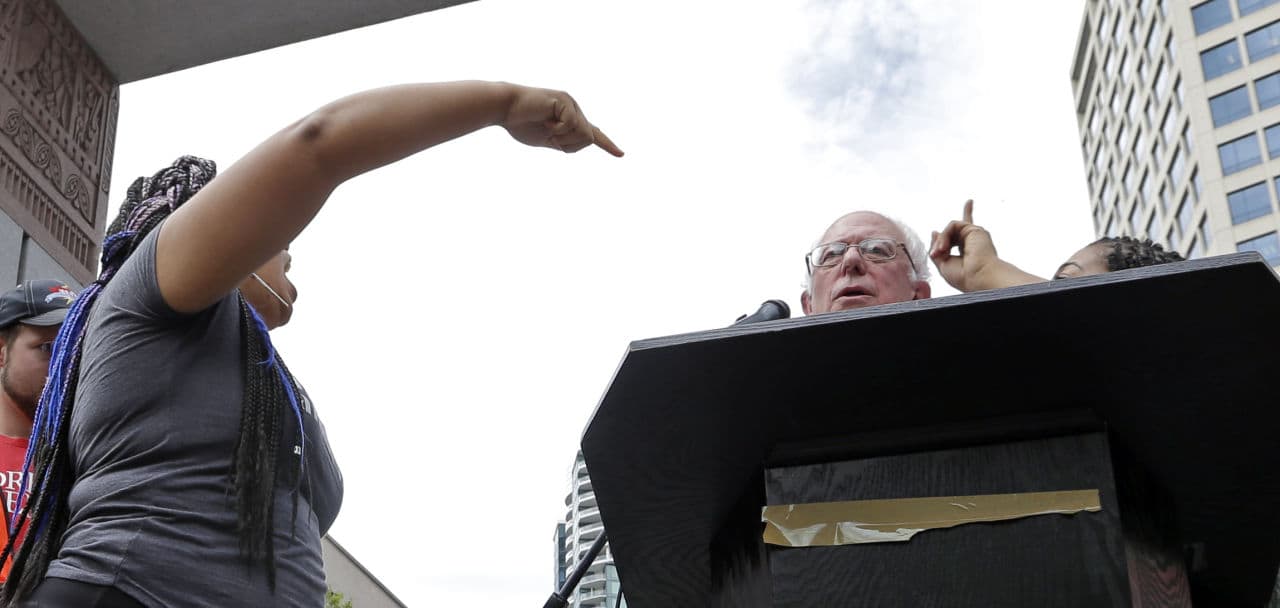

Third, when even Bernie Sanders fumbles in front of the Black Lives Matter movement, it's time for hard-headed examination of how too many officers treat African-Americans.

At a forum last month, the presidential candidate and poster-boy progressive was shouted down (along with competitor Martin O'Malley) by protesters, mostly African-American, angered at the duo’s reticence about black deaths at police hands. Within two weeks of the confrontation, Sanders’ stump speech was volunteering that “black lives do matter,” yet he was heckled off a Seattle stage recently over the same issue.

Let’s stipulate that it was not just undemocratic to deny voters the chance to hear a major candidate, but counterproductive as well. This wasn’t Donald Trump, after all, but Bernie Sanders, who said he would have addressed Black Lives Matter in Seattle if he’d been given half a chance to speak. Still, it takes an ostrich to deny that the string of police killings of blacks is an isolated aberration. Police body cameras, despite legitimate concerns, are worth the risk, raising the chances of catching bad police and exonerating good cops. But they aren’t enough; incriminating video evidence of excessive force last year in the chokehold killing of Eric Garner yielded no indictments.

One place to look for answers, ironically, is Cincinnati. Ironic, because that’s the city where a white cop stands accused of murdering unarmed black motorist Samuel DuBose. But DuBose’s killer is a university cop, not a municipal one, and that’s important: The Cincinnati PD is a model for the sea change needed in policing.

After race riots 14 years ago following an officer’s killing a black man, Cincinnati altered the way it policed and interacted with its black residents.

After race riots 14 years ago following an officer’s killing a black man, Cincinnati altered the way it policed and interacted with its black residents. A lengthy Atlantic article described how the key reform was something called community-oriented policing, which seeks to address problems leading to arrests before the arrests have to be made.

“If hospitals notice an inordinate number of emergency patients coming in with facial injuries due to glass beer bottles being broken over their heads in fights, as was the case in one British precinct, police work with the bottle manufacturer to make sure bottles are made out of material that won’t break,” the reporter wrote. “If police notice a woman is a repeat victim of domestic violence because her partner breaks into her ground-floor apartment, they work with the landlord to move her to a higher floor, link her to a social services agency and help her find free daycare so she doesn’t have to rely on her abusive spouse for help. In another example, when police noticed an increase in metal thefts in a neighborhood, they worked with property owners to paint their copper pipes green, posted signs about the pipes being painted green,and then informed scrap yards of the program to gain support, which led to a reduction in copper thefts.”

When Cincinnati police heard from residents that the neighborhood near a certain store was a hothouse of murders and drug dealing, they relocated a bus stop and phone booth to disperse loiterers, yanked the store’s liquor license, and got the city to raze the building to permit new development. Elsewhere, the police work with gang members and their families, trying to funnel violent people into better lives.

this approach requires police to park their cars, walk beats, and familiarize themselves with the people and problems of their neighborhoods.

The story stated the obvious, that this approach requires police to park their cars, walk beats, and familiarize themselves with the people and problems of their neighborhoods. I can imagine some grousing that this is social work, not police work. But there’s no arguing with success: According to the article, between 2008 and last year, arrests and crime dropped substantially.

This won’t be easy to implement nationally. Many Cincinnati officers resented criticism and resisted reform. The Justice Department had to investigate the department’s abuses and order it to change; the city spent years and $20 million-plus doing so. While police work doubtless attracts people with a desire to serve, some research suggests that wielding a gun and state power also attracts those of authoritarian bent. As the findings seem mixed, we should ask experts to referee the dispute and suggest any improvements to psychological screening of police applicants.

Meanwhile, candidates like Sanders might look to Cincinnati to devise the policing planks in their platforms. It might help, too, if well-intentioned protesters asked the candidates questions about reforms, rather than shout them down for the next year-plus.