Advertisement

The Value Of Family Heirlooms In A Digital Age

A small black marbled-paper box sat quietly in my spare bedroom, along with a hard cardboard barrel. The box contained a little boy’s blue wool suit and red hat embroidered “04” and worn by my paternal grandfather when he was 2-years-old (in 1885, if you’re counting).

The barrel protected my maternal grandmother’s December, 1899 white wool wedding gown from everything but a few moths, and a leather-covered wooden box held her matching, size "miniscule" shoes. (What line was I in when they gave out feet that small?)

The wallet belonging to my great-great-great-grandfather Samuel Church is another matter. It is of embossed leather, smooth and supple, with a strap that encompasses the entire fold. It contains the intent to marry of my great-great-grandparents Daniel and Mary Church, receipts for Samuel’s marble gravestone, and a note from my great grandmother Nellie giving the wallet to her son, my grandfather Rex, of The Blue Suit. It has been passed down from father to son to grandson and will go next to my son, as it should.

My Yankee family lived by the saying, “use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without” — especially, it would seem, when applied to the gold coins I’ve never found.

What I have found is the expensive difficulty of preserving, storing, conserving and generally taking care of photos, textiles, china, tools and all those articles of daily life that we take for granted until we have to store them. How long can we expect mementos to remain valued by a younger generation three generations removed from the original owner?

My son never met the lady who wore that wedding gown. He sees her as a leaf on the family tree...

My son never met the lady who wore that wedding gown. He sees her as a leaf on the family tree, not the grandmother who visited armed with small boxes of Sugar Pops in the days before sugar was a condemned substance. I can’t expect him to see the gown in the same way that my mother and I viewed it. I can take photos of it for a digital album, mark the photo with names, dates and places, and put it all on a CD for distribution to the family. But what happens to a gown neither “special” enough nor unusual enough to find its way into a museum’s textile collection, or too delicate to remain in that barrel?

A weightier question concerns all the family Bibles I have, including one printed in 1827 that belonged to my fifth great-grandfather on my father's side, John Church. My paternal great-great-grandmother kept in her deceased son’s Bible a lock of his hair, and there’s my maternal great grandmother Lee’s 15-pounder. Museums, historical societies and other such organizations are eager to receive the genealogical information contained in these books, but none have the storage space to appropriately store the Bibles themselves. So the family births, deaths, marriages and other notes have been photocopied and scanned, a digital record of events my ancestors took great care to record. I’m lucky because I have chaplain friends who collect and treasure old Bibles, and a namesake cousin who wants the weighty one.

These objects tell me that my ancestral family is not a dream or a boring romance novel. They lived, worked, saved, and died with these heirlooms left in my care. While I can sell my 226-year-old family homestead with significant conflict but minimal tears, I have a hard time disposing of these things so highly valued by my ancestors that they preserved them. What is anyone’s obligation in this situation? I am a daughter, granddaughter, and great-granddaughter, not an archivist (says so on my college diploma), a custodian of house and home by default, a job everyone appreciates but no one else really wants.

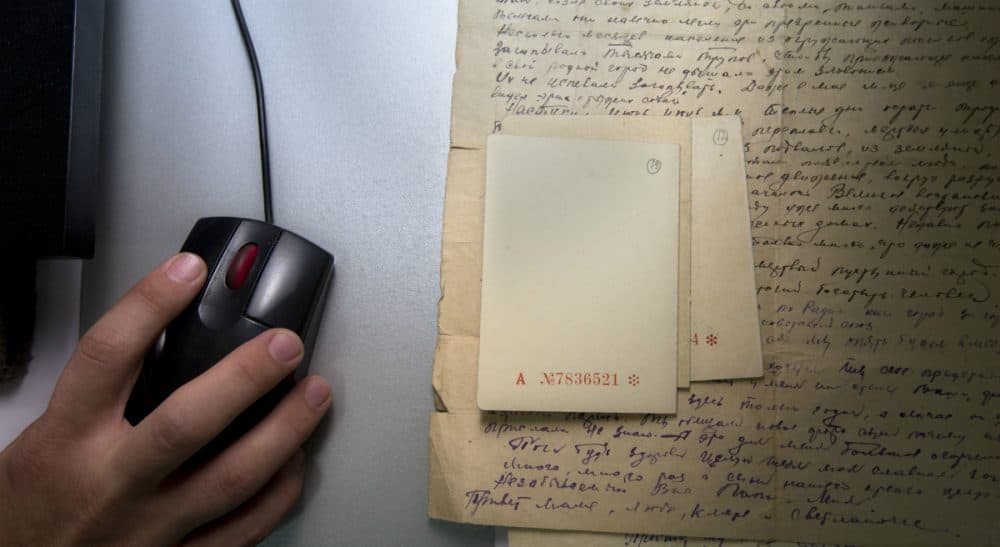

Now, as we prepare to “downsize” our household, I have to consider the fate of these heirlooms as I try to decide which of my own belongings are heirloom-worthy for the next generation, all of which will add to the bins of memorabilia already multiplying in dark corners. It’s tempting to procrastinate entirely and leave it all for my children to deal with, as it was left for me. I am only one “family historian” who knows some of the intimacies of these heirlooms, so perhaps it’s okay that I be the one to donate, delegate, dispose of and digitize the artifacts and stories that make up my family’s long history.

Wedding gown, anyone?