Advertisement

In A Trove Of Their Divorced Parents' Letters, 3 Adult Daughters Find Solace

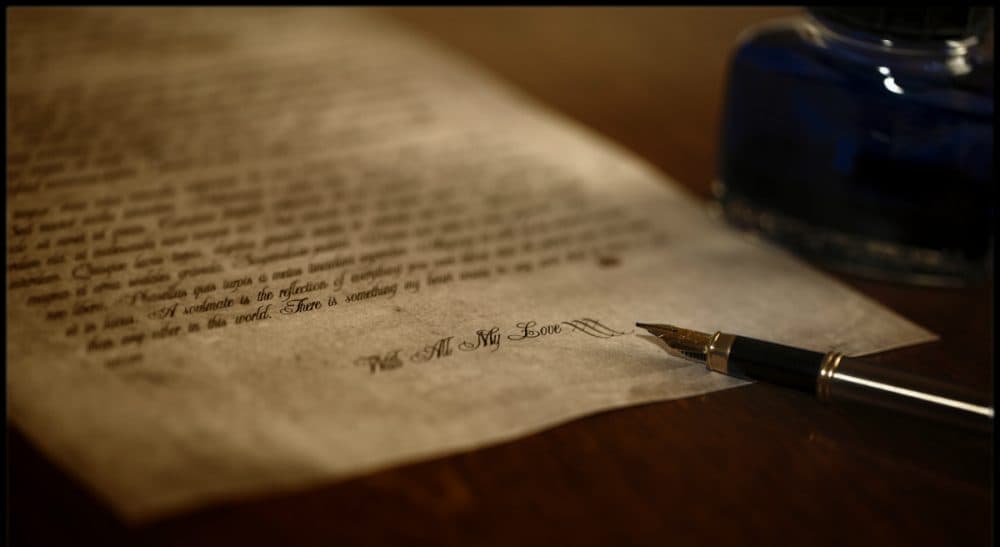

When my mother died, our father returned for a post-memorial reception in the house where we’d lived while still an intact family. A blazing fire in the wide stone hearth thawed our slightly chilly reunion. Its warmth inspired my younger sister to hand him a cache of love letters we’d found among Mom’s belongings. Dad barely glanced at the precious packet before tossing it into the flames, singeing our hearts, we three daughters of divorce.

What seemed to us like a heartless action may have been understandable, given that Dad’s second marriage, at least according to him, was a happy one. But we could not forgive his indifference: He’d gone away and left us with our mother’s hurt and gradual decline.

So when my sister later discovered a second letter trove, we kept them a secret from him, blithely ignoring copyright law, which makes clear that he was the rightful owner of any and all letters he’d penned.

Dad barely glanced at the precious packet [of letters] before tossing it into the flames, singeing our hearts, we three daughters of divorce.

Like other children of divorced parents, we’d always yearned to know why their conjugal bond had frayed. As Dad tells it, a marriage counselor had advised him that if he loved Mom he must leave her. Otherwise, she would never stop drinking, which would surely kill her.

We never quite believed Dad’s self-serving tale. Underneath our skepticism lay a deeper worry: Was it one of us who’d strained their relationship to the breaking point? Was it my older sister, for interrupting their love as a couple and for causing my mother to give up her social work career? Was it my birth barely a year later that drove her to drink — just evening cocktails at first, but eventually at any time of the day? Was it the third child, conceived seven years later, perhaps to shore up a shaky union, simply too much of a burden?

We looked for clues in the second set of letters that we’d kept for ourselves, each folded into an envelope affixed with 3-cent stamps. Most were written on hotel stationery, since in his job as a fundraiser for Eisenhower, polio research or aid to medical education, he traveled around the country. He wrote home from Chicago, Philadelphia or San Francisco.

In one letter, his script jumps around: He’s writing from a moving train. In another, sweat blurs the ink as he complains, “It’s hot as Hades here.” He writes about loneliness and longing, and in one, he reminds her of “last night,” referring, I suppose, to sex.

Each missive starts “Sweetheart,” “My Darling Marian” or “My Adorable Wife.” Most of the letters proclaim their “shared philosophy of life and love,” and profess to an enduring commitment. “Ours is a beautiful love,” he declares.“We must always realize it is something very few people seem to attain let alone return it as we do and shall do.”

My mother responds with equal fervor (our cache includes copies of her letters to him): “How I wish one small portion of this moonlit night could be warmed by the closeness of two people who warm each other as happily as I feel we do. Wonderingly yours, Marian.”

Even in summertime, they had little time together. Mom took us girls to the family cottage in the Poconos, escaping city crowds and polio risks, while Dad raised money to end that dread disease. He would join us only on weekends. A brief mention in one of her letters gives me a frisson of dread. “Stroudsburg holds no hope for beer, wine, or ANY drink, so if you could bring rum or whatever you could get, I’d really like some.”

Another ends: “Linda wants a coloring book with teddies,” followed by “Will you please bring some liquor?”

I want to say: Don’t ask for that, Mom. Don’t you realize what it will do to all of us?

Despite... inklings of their marriage’s downfall, our parents’ letters make clear that we were not the cause.

Despite such inklings of their marriage’s downfall, our parents’ letters make clear that we were not the cause. My mother writes: “I’d like to feel we are giving them every chance we can to grow into happy girls. They are so sweet and trusting, so full of a readiness for life.” My father writes, “I’d like to have you all here -- just for an hour a day so that I could drink in each of you and enjoy the sweetness of life as it is to be enjoyed.”

We three children, plus Dad’s travel-heavy job, did leave our parents little time to “enjoy the sweetness of life” together as a twosome. But their letters give us what we’d yearned for: reassurance that they both fully loved us, and once fully loved each other.

So no, Dad, you can’t have your letters. We’re keeping them for ourselves, to read and re-read, to love and to cherish, till death do we part.