Advertisement

Commentary

The Mirror Of Ourselves: Facing History In Order Not To Repeat It

The upset world that we live in seems resolute, like a pouting child, to block its ears and shut its eyes to history. We giggle with satisfaction when irresponsible senior politicians such as the United Kingdom’s new foreign secretary, who, in his make-believe sandbox, construed the EU as an effort to reignite Hitler’s European superstate goals. We pine for fairy tales of past glory that bear little relation to reality. Like children creeping into a shabby old hideout we've named paradise, we hope against hope that we can remain in that pretend place and never have to grow up. Even most of us who aren’t Trump supporters, who felt the weight of the grim day when Britain voted for Brexit, and who watch with dread as all sense of moderation drains away, can at some level identify with these emotions.

My perspectives are influenced by the troublesome knowledge that the past has always been very present in my life. A little over six years ago, I visited the German Federal Archives in Berlin to learn of my grandparents’ role in National Socialism and the SS. My grandfather, as I would learn, was an SS Special Führer for Landed Estates in East Prussia and Poland. He was tasked with turning occupied Poland into the breadbasket of the Third Reich through the deportation of the existing landowners and the enslavement, torture and murder of the local population.

In my youth, Jews were mentioned in hushed tones, as though they were dangerous to us, and I had listened to my lucid and well-read grandmother argue that the Holocaust had never happened.

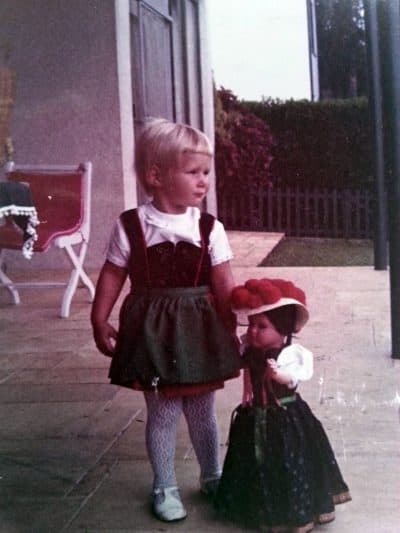

Several trusted friends, including a Jewish friend who had fled Germany during National Socialism, warned against my inquiry. To them, my story — born in Brazil, and with a maternal family that had spent the duration of the Second World War in occupied Poland — was obvious: I had been raised to avert my gaze from the ugliest truths.

I was the child that had lived in the hideout, but there was at least one thing that made it uncomfortable to be there: the shame that burned inside. In my youth, Jews were mentioned in hushed tones, as though they were dangerous to us, and I had listened to my lucid and well-read grandmother argue that the Holocaust had never happened. I didn’t like what she said, but, without believing her, swallowed it like ill-tasting food, hoping in return to be able to cling to her affection.

As the decades passed, I began to feel the inner plague of the bystander. Yet, to step out of my conditioning would have many consequences. Was I prepared for them? I was frightened, but the cramping in that hideout had become so extreme that there was no other choice but to face history.

During six years of tunnel-vision research, I visited many archives in Germany, Poland and Brazil and interviewed eyewitnesses and victims of the Holocaust. Some, understandably, didn’t want to speak to me because of what my grandfather had done to them. Others saw it as their duty to end my inherited guilt. An old man with a scar over his eye from a wound inflicted by my grandfather when, as a young boy, he had forgotten to remove his cap when the SS walked past him, said: “It wasn’t your fault. You didn’t do anything.”

During these years when I left unreality, the nations of the world had begun to creep back into their hideouts. History had become the mirror of ourselves. In the shouting of demagogues across Europe and the United States, who used the opportunity of the refugee crisis to justify their underlying racism and thirst for power, I heard my grandfather’s shouting. It was one of those qualities that eyewitnesses in Poland and Brazil remembered without exception. “He liked to scream,” they said.

Advertisement

The victims and their descendants continued to speak out, but it seemed that no one could hear them above the opportunists who, to thunderous applause, yelled for tracking and excluding certain groups based on their religious beliefs. Amid all this, the families of the perpetrators remained comparatively silent, bound by old taboos designed to keep them from the pain of inherited guilt and the indignation of remembering. Their families, too, had suffered in the war.

We have the responsibility to tell the world that our forebears were people like you and me, capable of the best and the worst that humans can be.

In northern Germany, I visited rural communities where my grandparents had once lived and that, from 1933 to 1945, had been strongholds of National Socialism. I felt like an elephant in a china store as I crashed my way through the subtle codes established over decades in order to avoid discussion of what had happened. At a national level, Germany has done more than any other nation to face the terror of that time. Yet, in the small towns and villages, and, above all, in families, a destructive silence still governs. I begged the locals with my eyes: We have the responsibility to tell the world that our forebears were people like you and me, capable of the best and the worst that humans can be.

And in South America, in the only eatery in the small border outpost town between Paraguay and Brazil where my grandparents had once found a haven from justice, people shook their heads at the corruption crisis bringing down the government. An elderly man who knew my grandfather stopped at our table. “A pity Hitler didn’t win the war. Things would have been much better,” he said, referring to the lack of order that he believed the pestilence of democracy had brought. In this moment, as in countless others during the past years, it became clear to me that we are living at a pivotal time when we have the possibility to fly forward into bright humanity, yet so many long for the shabbiest of old places.

History need not be the mirror of ourselves if we dare to face it.

Editor's update: After it was first published, this essay sparked a special series, produced in collaboration with WBUR's Kind World. Explore "Beyond Sides Of History" here.