Advertisement

The Ring Around The Three Of Us

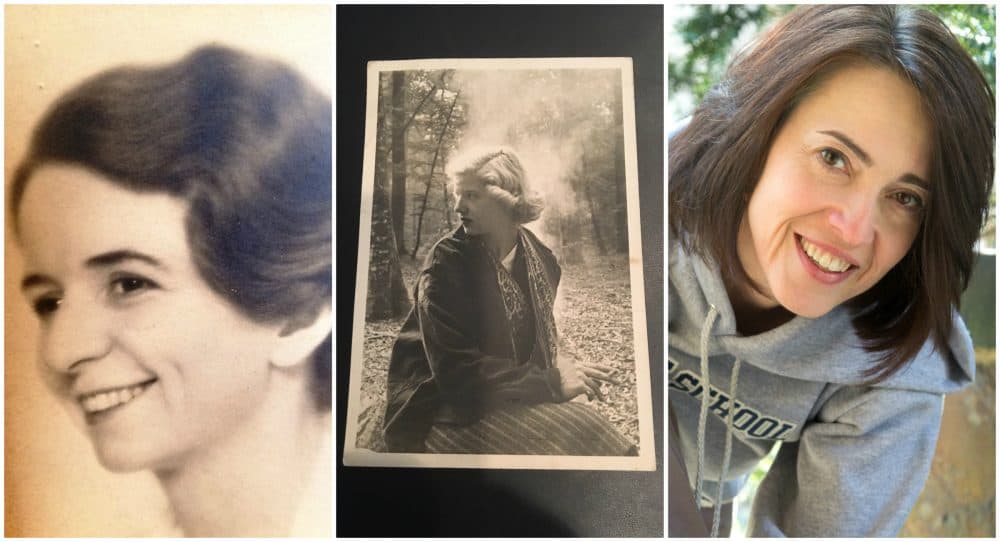

My aunt Aya mailed me my grandmother’s engagement ring in a cigarette carton. When my grandmother died it was sudden. She was on a seaside vacation in France when my father was just 14. She was 46. In the only photo I have of her, she is smiling warmly, her hair bobbed with a Marcel wave.

Your Toll House cookie kind of relative, Aya was not. Our annual holiday greetings over the telephone were usually accompanied by the sound of ice clinking in her scotch tumbler. She could describe failing body parts in encyclopedic detail. She could be vulgar and cranky. She needled my father, her brother, constantly.

Aya started sending me pieces of her mother’s jewelry after my 21st birthday, a necklace, a stick-pin, her engagement ring.

Aya could write poetry. She attended the now defunct Bradford Junior College in Haverhill. I could write too. I was bold. I was irreverent. In high school, I boycotted my senior prom. Proms were too establishment for me and my friends. We traded tuxes and satin dresses for jean jackets and had a Frisbee party in the park. A magazine editor wanted to publish the essay I wrote about it. Would I make some edits? I never did. It went unpublished.

No children, although Aya married twice. She tried to throw herself out a third floor window when her mother died. She was lost. There were rumors: she had an abortion in the 1950s. Her first husband was killed in a car crash soon after they were married. She lived with her second husband in Florida. They fought. They were once arrested in a domestic dispute. She stayed overnight in a jail cell where she befriended a prostitute.

Aya started sending me pieces of her mother’s jewelry after my 21st birthday, a necklace, a stick-pin, her engagement ring. I recognized the gesture on Aya's part, but it also meant a connection I wasn’t seeking.

When I was still single, she telephoned. “So, why aren’t you married yet?” she barked. A long lecture was in the offing.

“Well, I‘m pretty fed up with men these days,” I said. “Women are so much nicer.” Could I shock her into disowning me? I continued, “But I like penises better.”

"Sure," she said. "If you can get them to ... meet expectations!"

Her timing was perfect. She was funny. She was cheeky. She was me.

When I married she sent me 10 engraved silver spoons that belonged to my grandmother. But what I really wanted was to read her poetry. “Oh, I never kept that rubbish,” was always her answer.

Sometimes Aya would ask if I’d visit her in Florida. But I kept her at arm’s length. Instead, I told her how often people stopped me to admire her mother’s ring. The stone is a peridot — the color green the sea turns in a summer storm. Art Deco in style, the setting has a half-naked woman with wings, displaying the stone on her shoulders. When they did, I told her, I would feel her mother, my grandmother settling protectively over me, this woman I never knew.

Advertisement

The truth was I was afraid to visit Aya. I worried that I might see myself in her. I worried that I would confront what a life cut short of its promise looked like. I worried that I would see the ravages wrought from a void of the loss of a mother so young. I have a teenage son. Like most mothers, I have experienced that sweat-drenched fear for him, when awaking from fitful sleep.

After Aya died, we interred her ashes in the family plot north of Boston. My father read one of her poems, unearthed by her neighbor. Over lunch, a friend spoke of Aya’s humor, especially the raunchy kind. Details were filled in. She had divorced her first husband, there was no car crash. There were two abortions, not one. She wanted to be a writer. As a girl living in France, she lost her virginity to a man who became a prolific novelist. Even in her 70s, she slept in the nude.

Sometimes when I am rooting around for the back of an earring, I find my grandmother’s ring in my jewelry box. I see tempests and still waters in its green stone. I see two lives cut short...

Aya and I were different, but were we cut from the same cloth? I worried. At mid-life, had I turned away from my own potential? Maybe there isn't just one moment, but a series of tiny decisions whose significance at the time, we are blind to. When combined, they shift the arc of one's life for better or worse.

Married, I wear my own engagement ring now. I have a family of four kids. I measure my days not in terms of one big regret, but in little daily decisions, the ones, easy to ignore when dirty dishes wait. I write more, and I've been published with some regularity.

Sometimes when I am rooting around for the back of an earring, I find my grandmother’s ring in my jewelry box. I see tempests and still waters in its green stone. I see two lives cut short: my grandmother, who died too young, and her daughter, whose days got snagged on life’s bramble.

I suppose, then, it is my life that is their continuity. There are days that this frightens me. And days that the warmth of it, spreads over me like a mid afternoon sun streaming through the windows.