Advertisement

With Love, From Harold: A Father’s War Story Offers Hope In An Uncertain Time

COMMENTARY

The Second World War made my father an American. The Holocaust made him a Jew. And the confluence of those two events made him the bravest of the brave.

By the time dad graduated college he had already been recruited to be a 90-Day Wonder. He, and other young men like him, were fast-tracked to become military officers. It was 1940. For three months my dad was immersed in training at the Brooklyn Naval Yard. He was 21 years old and when he finally came up for air he was saluted as an ensign.

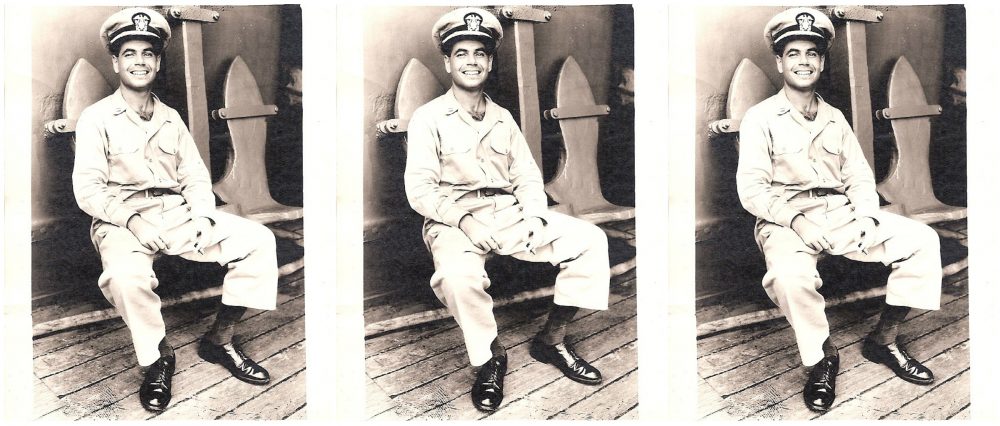

One of my favorite photographs of my father was the one that I turned up snooping in his dresser as a little girl. My father had sent the 3 x 5 black and white picture to my grandmother. He dated the back of the photograph 1941 and signed it, “With love, from Harold.” Barely a year out of Yale, he was most likely running guns and butter to Greenland just before Pearl Harbor. In the picture, he is below deck where it is dark and windowless — a circumstance that must have made my father claustrophobic given his later penchant for observing a vast sky of weather. When he tracked a storm from my bedroom window his gaze was dreamy, suggesting that he was still drifting on his supply ship. But my father never coasted for long. He eventually righted himself to know exactly where he was going.

“With love, from Harold.”

I recognize that love. A desperate love born of a certain time. A love wrapped in loneliness. In the wake of the election I know this love intimately. As I texted my sister and comforted my young daughter, that was the love I felt in the early morning hours of Donald Trump’s election to the presidency. A couple of weeks later, I joined the rally on the steps of the State House against the hate crimes occurring across Massachusetts. Boston Mayor Marty Walsh talked about love. But with love comes a vigilance when fear lurks in the background.

I once asked Dad if he was scared back then. “Not at all,” he said crisply.

My father’s war picture shows a man who had lost a lot of weight from adrenaline rushes anticipating an oncoming war and the compulsory exercise to prepare for it. He must have punched extra holes in his belt. His officer’s cap fell below his ears as if from the weight of his brassy naval insignia. His Adam’s apple was prominent and his neck muscles taut.

I focused on his shirt, the top button undone, so that I could almost make out the chain of his dog tags. But the longer I stared, the more it faded away. I knew definitively those tags were stamped with an "H" that stood for the biblical-sounding descriptor — Hebrew. Dad told me as much. My assimilated grandparents were nervous about sending their son out in the world as a Jew. They had heard bits and pieces of news coming out of Europe. Hitler was a menace. Jews were harassed, arrested, even deported. Father Coughlin was on the radio. Isolationism was the prevailing politics. America’s geography suggested a false kind of safety.

I once asked Dad if he was scared back then. “Not at all,” he said crisply. Yet even with his “this too shall pass” disposition, I know that if he were still alive he would consider alt-right a euphemism for white supremacy. But what would he say about Steve Bannon having the ear of the president-elect? He’d seen the Bannons of the world rise up before. We need to stand firm, Dad would say. I try and translate what that means today. How do we protest appointments and policies that simply cannot stand? I think I know Dad’s answer. He was the man who sternly told a guest in our house not to spew her racism in front of my siblings and me. I’m sure he would have approved of the postcard I sent to President-elect Trump with the message: "Not Bannon." Small acts of protest can have a meaningful ripple effect for years to come, he'd tell me.

My grandparents begged my father not to identify as a Jew in case he was captured. But my father, who lip-synced prayers on the rare occasions he went to temple, would not wear dog tags stamped with an "O" that stood for Other. In Dad’s military, O functioned like the universal blood type. O accepted the last rites from any religious tradition. But in the end, that kind of open-endedness was not for my father. If it came to it, he would die as a Jew.

These days I contrast the khaki-uniformed photograph of Dad with another one of him in full naval dress. That formal, flawless black and white portrait, in which it looks as if cotton batting is the backdrop, was displayed in our living room forever. Now it stands vigil in my mother’s small dorm-like room in a nursing home. This is the picture that would have accompanied the obituary if my father had died in the war. And in these post-election days, I take comfort that at the time both pictures were taken my father was not afraid of the future. I hope one day I can share his optimism.