Advertisement

Commentary

The 9th Of November: From Kristallnacht To Trump

When Hitler moved to Munich from his home country of Austria, he was a loner — a failing artist who had spent his recent years selling painted postcards on the streets of Vienna. It was a perfect storm of events that led him to power in 1933.

World War I had left Germany weak, broke and with a bruised ego. In 1919, Hitler found the German Workers’ Party, a small group of men who spent most of their time talking about how much better life was before the war. He stepped in as leader. In 1923, he was jailed and it was there that he met Rudolf Hess who ghostwrote Hitler’s "Mein Kampf," the infamous Nazi handbook.

When we speak of World War II, we often focus on a story that begins in 1939 and ends in 1945. Looking at history in such a limited scope is counterproductive to learning from the past.

Hitler did not introduce anti-Semitism into Europe. As early as the year 306, there were anti-Jewish decrees. World War I had actually helped Jews assimilate into Germany, similar to the way the world wars helped immigrants and African-Americans in the United States. What Hitler did was change anti-Semitism from religious and cultural prejudice to racism.

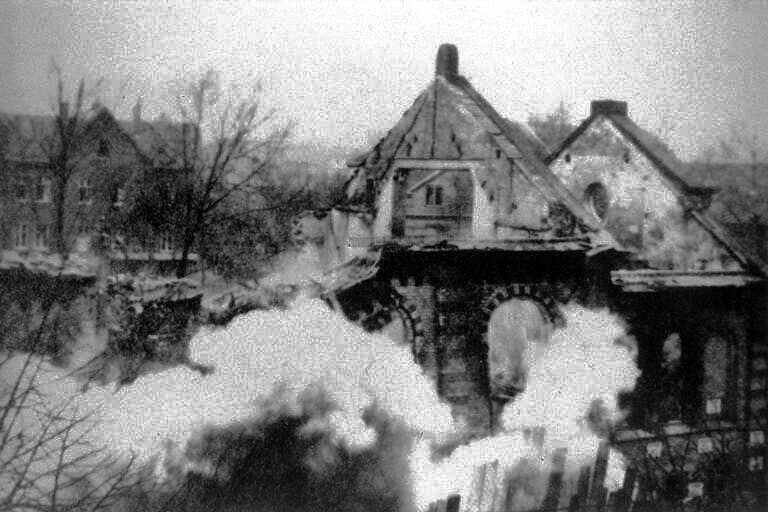

November 9, 1938 became known in Germany as Kristallnacht, or "The Night of Broken Glass." This was the first major action of the Holocaust and it was five years after Hitler gained power. By this time, Hitler had spent so many years spewing anti-Semitic rhetoric to the German people that it was easy to encourage the masses to act violently.

Riots continued for two days across Germany. In that time, synagogues were burned, windows of Jewish stores were broken, then looted. Many Germans, including the police, just stood and watched. Jews who tried to put out fires or defend their property were arrested. In total, over 100 synagogues were burned and more than 7,500 stores were destroyed. When the violence ended, Jews had to pay for the damage. The government enacted additional anti-Jewish laws.

The bystanders assumed that one day soon, Hitler and his Nazi party would be voted out of office and everything would return to normal.

This story played on repeat in my mind in the early hours of November 9, 2016. On the anniversary of Kristallnacht, Trump, a man rumored to sleep with Hitler’s speeches next to his bed, was declared the 45th president of the United States.

Over the past year, there has been important discussion comparing current American politics to the rise of the Nazi party in Germany. In order for this conversation to remain constructive, we can isolate parallel themes — but we must also recognize key places where the past and present diverge.

We live in a different technological age now. ... We can fuel love as easily as we fuel hate.

We are seeing the power of false truths reemerge. The Nazi Minister of Propaganda, Paul Josef Goebbels stated, “Any lie, frequently repeated, will gradually gain acceptance.” Hitler, in Mein Kampf, wrote “[Propaganda] must confine itself to a very few points and repeat them endlessly.”

According to the Washington Post, as of early August, Trump had made over 1,000 false or misleading claims: “He averages nearly five claims a day … More than 30 of the president’s misleading statements have been repeated three or more times.”

In America, within 10 days of Trump’s election, the Southern Poverty Law Center tracked 900 bias-related incidents against minorities. In the same period, neo-Nazi Richard Spencer gave a ‘Hail Trump’ to over 200 attendees at an annual conference. Similar events, such as far-right rallies in countries like Sweden, celebrated Trump’s win.

These groups are not new or nor have their ideologies just been developed; but Trump has given them permission. He, as the Nazis did with anti-Semitism, has made it okay to turn prejudice into discrimination.

As alarming as this feels, we must work towards progress by noting differences.

We live in a different technological age now. We can mobilize through social media in a way that was not possible during World War II. We can fuel love as easily as we fuel hate.

The internet has become a key player in our resistance. The Women’s March was a fantastic example of this. An idea online became a worldwide protest with 408 marches in the United States and 168 marches in 81 other countries. The day after Trump’s inauguration, people from all seven continents stood together to advocate for human rights. Far more people gathered to protest Trump than to support him.

While the Nazi agenda rose in popularity throughout the 1920s and 1930s, we are witnessing the opposite. Trump’s approval rating is an unprecedented 33 percent and dropping. The 200 people that Spencer spoke to after Trump’s election in 2016 is significantly less than the 20,000 Americans who gathered at Madison Square Garden in 1939 for a pro-Nazi rally.

Although we took a few steps backward in this past year, we are still moving forward. But we must remember the ninth of November, a day that forever should be seen as a warning shot of what can happen if we aren’t active participants in our democracy.