Advertisement

Commentary

We Expect More From Our Leaders When They Communicate — But Why?

Recently, one of my colleagues considered aloud whether she should include material from the current administration on her fall syllabus. Past readings in her course offered well-constructed examples of cogent and coherent political rhetoric — embodying many of the principles (logos, ethos, pathos) that we teach students to recognize and replicate in their own work. For a moment, we collectively wondered, could one select speeches and off-the-cuff monologues from President Trump as ideal examples of their genres?

Simply put: No.

Yes, such examples could be chosen and even held side-by-side up for comparative analysis with other more polished speakers. Might that be viewed as too partisan?

Maybe.

Or, politics aside, wouldn’t it basically be the equivalent of giving students a leading question? (Even at the start of the semester, students are keenly aware that there is no contest in rhetorical fluency and lexical mastery between our last and current president.)

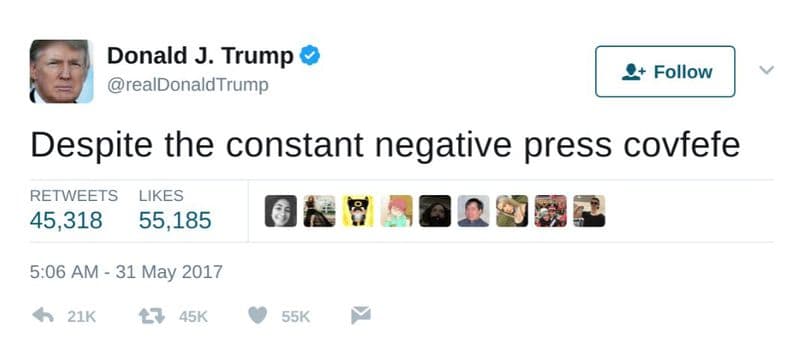

...shouldn’t we be able to engage with a president’s policies and ideas without first having to puzzle over the words (cf. "covfefe") and their meaning?

As teachers of rhetoric, not only do we want to teach students how to ably communicate their ideas with precision and accuracy, but to do so in standard written English — with a clear understanding of audience and genre. We tell them that these things are important, essential even — but when the individual holding (arguably) the most prestigious professional position in the United States routinely violates the “rules” of language usage, does that undermine our advocacy for best practices, or strengthen it?

After this summer's violence in Charlottesville, Trump was criticized for not speaking out directly toward white supremacist activity and instead noting that he “saw many sides” to the conflict. Many, including Gregory Clark, president of the Rhetoric Society of America, spoke out against Trump’s response, which he characterized as “rhetrickery.” Seemingly undeterred by such criticism, in the days following, Trump posted on Twitter that “Sometimes you need protest in order to heal, & we will heal, & be stronger than ever before!”

That final version followed three earlier versions with misspellings, including those that suggested, “we will heel.”

Farhad Manjoo argues that linguistic gaffes such as these should be viewed as minor missteps, not a marker of one’s intellect or communicative capacity. He suggests, “Misspelling has become a mostly forgivable mistake” and notes that due to the 24/7 accessibility of digital platforms, “immediacy invites error…and error suggests humanity.”

Sure, we all make errors when communicating online. And autocorrect can wreak havoc on text exchanges. But when we are communicating in public, the stakes are higher. And we must teach students that they should work toward that ideal.

President Trump’s laxity of language has prompted columnist Charles Blow to argue that the “degradation of the language is one of Trump’s most grievous sins” and that “[he] has the intellectual depth of a coat of paint.”

The latter assessment may be untrue — and may also be unkind, but the point is this: Shouldn’t we be able to engage with a president’s policies and ideas without first having to puzzle over the words (cf. "covfefe") and their meaning?

In October 2009, then-U.K. Prime Minister Gordon Brown made international news when he misspelled the name of a soldier killed in Afghanistan in a handwritten condolence note sent to the family. The soldier’s mother criticized Brown for being disrespectful after this error. That semester, I used the example with students in my writing class — to underscore the importance of checking one’s work, lest they end up as the lead story on the BBC World News. It also sparked an interesting class discussion that pointed to broad consensus: We expect more from our leaders when they communicate. But why?

The short answer may be that we want to feel that those who hold positions of power excel in all areas — including their use of language. Further, communication errors, whether abstract or concrete, are distracting. They take the focus away from the topic at hand. Take, for example, the follow up response online to Trump’s “heel” mistake. New hashtags were introduced (#heel, #idiot). People, like user @JulieLeto, responded directly on Twitter: “For our country to heal, the heel in the White House needs to say that he’ll resign.”

Twenty-five years ago, then Vice President Dan Quayle found himself the punch line of a joke from which he never fully recovered after he corrected a student during a practice spelling bee session. Quayle told the student to correct “potato” to read “potatoe.” The incident served as late-night comedic fodder for a long time after.

Harsh? Sure. But the fact of the matter is: Mistakes in grammatical usage or opacity in the communication of ideas does not project a strong sense of ethos. And that is something we do want students to project, long after they leave the classroom.

This semester, my writing class is focused on writing science for the public. To succeed, these future leaders will need to engage with the broader public. I, and my colleagues, then would be doing them a disservice if we suggested that attentiveness to detail (in accuracy, arrangement, and yes — even spelling) were no longer important. All words matter.

To return to my earlier question: do consistent examples of precipitate Twitterspeak and alternate facts undermine our teaching rhetorical “best practices”? Not at all. Rather, they offer our students a clear Exhibit A as to what happens when speakers — even those in power — abandon the conventions of clear communication: after awhile, it becomes just noise.

And eventually, people may just stop listening.