Advertisement

Commentary

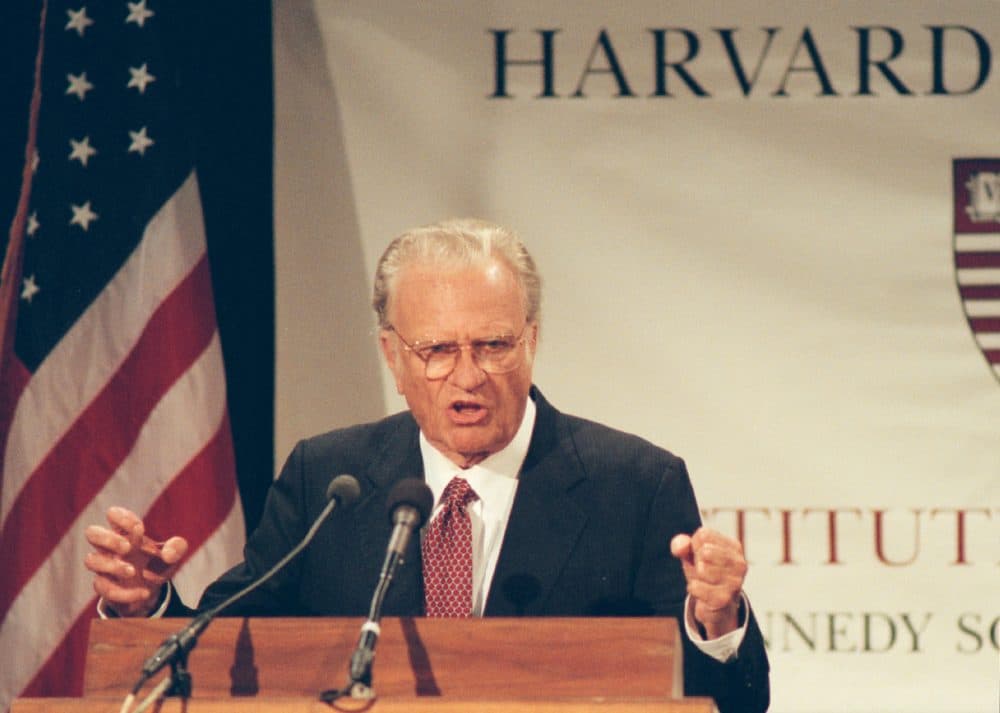

When Billy Graham Preached At Harvard

When I heard the news of Rev. Billy Graham’s death last week, I thought immediately of the moment almost 20 years ago when I met him, for the first and only time, in the most unlikely of places — Harvard Yard.

He had been invited to come as a guest preacher in the university church the previous year, but already his failing health had prevented that appearance. This time he was up for the journey, and it fell to me as a seminarian -- a theological term for “intern” — to make him welcome, make sure the water pitcher was filled and basically, stay out of sight.

The sorts of people who filled stadiums to witness Graham's crusade in the late 1950s and 1960s would doubtless have been surprised that he had willingly agreed — not just once, but twice — to speak at “godless Harvard.” Even in those days, before our culture wars turned violent, elite institutions of higher education were generally seen as the hostile camp by those caught up in what the economic historian Robert Fogel called the “Fourth Great Awakening.”

Even in coming to Harvard’s church, he was coming — knowingly — to a place where the senior pastor was a gay man. Peter Gomes had announced his sexual orientation as a public objection to the claim of campus evangelicals that AIDS was somehow God’s judgment of homosexuality. Yet Graham had warmly accepted his invitation.

Graham’s presence at Harvard was equally surprising to the people who made up Harvard itself. About the last revivalist preacher to come through the place had been Phillips Brooks, and that had been a century earlier. In a place where the intellectual superstars were those who had already proclaimed the final irrelevance of religion — a stance that needed some adjustment three years later, after the events of 9/11 — Graham was perhaps welcomed more as a cultural curiosity, not the bearer of an urgent message.

But that was how he saw himself, first, last and always. About the only person who was unsurprised that Billy Graham was waiting in the preacher’s room that Sunday morning for the 11:00 service was Billy Graham.

I was then, and remain today, a member of one of the progressive, mainline Protestant traditions that were at their high-water mark when Graham burst onto the scene in the 1950s. Most could not imagine it then, but Graham and his movement were in no small way forces that would ultimately undo the dominance of those institutions and set them on their long course of decline.

Linking together new forms of media with the spiritual dislocation of the shift to suburbia and the first expressions of suspicion toward large institutions, Graham galvanized a spiritual movement that thrived outside established structures. If he was a disciple of Jesus, he was also an apostle of Marshall McLuhan, understanding instinctively that television was the medium that was his message, and that gave him a means of communicating directly to an audience eager to link spiritual questing with individual autonomy.

Yet Graham was a conundrum to his followers as well. He possessed discipline and humility in equal measures -- qualities almost never found in the scandal-ridden pretenders who sought to be his successors. He wasted almost no time critiquing the views of “liberal” churches, a favorite fetish of much of the rest of the conservative evangelical movement.

And he kept at arms’ length the growing hunger for political power that characterized the generation of those who followed him. Radically focused on the personal, not the institutional, the “pastor to presidents” was much more interested in attending to the troubled consciences of individual leaders, whom he saw as no more or less in need than the thousands who sat in his stadiums.

When I came to the Yard early that morning, the first thing I noticed was an enormous crowd of students that had slept on the porch the night before — in order to get a seat when the doors opened. I knew some of them. They weren’t all Christian; they were just fascinated. I shot a questioning glance to the cop who had been standing by since 7:00 that morning; he just shrugged. “No trouble all night,” he said.

Waiting in the preacher’s room with my boss, Graham wanted to meet everyone else who was there preparing for the event. When you shook his hand, he fixed you with ice-blue eyes under a falcon-like brow — offset by a smile of profound gentleness. And when he asked you about yourself, and what you were doing there and how things were with you, you felt in that moment like the center of the entire universe.

For him, of course, the point was that you were important — important enough for God to notice. Graham’s passion was less about getting people to follow a specific version of Christianity than getting people to understand that their souls were a matter of terrific, even urgent, importance. That message will be missed.