Advertisement

Commentary

Why 'Wild Wild Country' — The Bizarre Tale Of A Free-Love Cult In The American West — Resonates Today

A caravan of would-be immigrants is camped at the U.S. border awaiting processing while a minority of the U.S. population clamors for a wall to keep them out. Investigations into if and how elections have been manipulated play out in the press and behind closed-door Congressional hearings. Donald Trump is loved by his base for being a defender of American culture and vilified by his critics for poisoning it at its roots.

It’s no wonder that "Wild, Wild Country," the new documentary series from Netflix, has become an unlikely but viral addiction. Documenting the rise and fall of Indian guru, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, his lieutenant Ma Anand Sheela, and the city of Rajneeshpuram, the city built by his followers in the midst of Oregon wilderness in the early 1980s, the story resonates today because of the unsettling questions it raises about the nature of community, leadership, and democracy.

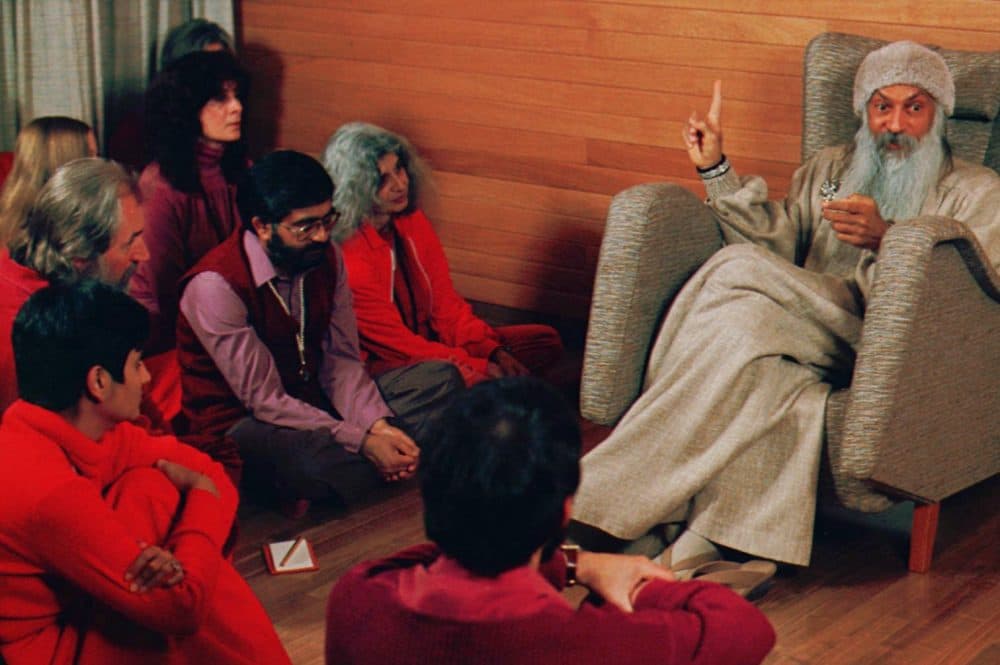

Bhagwan (as he is generally referred to in the series) was a philosopher and spiritual leader who came to prominence in the 1970s. Opposed to religious orthodoxy and rejecting asceticism, he preached a mashup of mysticism, capitalism, and sexual liberation. Though he succeeded in establishing a thriving “destination” ashram in India, the active animus of the Indian government he opposed led him to look for a newer, safer, and larger home for his commune.

Enter Sheela, a young woman raised in India, college-educated in New Jersey, and enamored of Bhagwan. In 1981, at the age of 31, she was appointed to be his personal secretary, and authorized to purchase a 60,000 acre ranch in Oregon. Roughly 2,500 followers of Rajneesh (referred to as both “sannyasin” and “Rajneeshis”) from around the world moved there and with remarkable speed and efficiency, built the self-sustaining city of Rajneeshpuram.

Meanwhile, the 60 to 90 residents of Antelope, the closest town (about 20 miles away from the ranch) felt mounting discomfort with their new neighbors. After all, these interlopers had come from all over the world, not just the United States. They all dressed in shades of red, purple, and orange; danced ecstatically, sunbathed in the nude, celebrated sex, and lined the road in and out of town to throw flowers on the hood of the Rolls Royce carrying Bhagwan to and from his house. With Jonestown a not-too-distant memory, the elderly white Christians of Antelope viewed the multi-national, multi-racial, predominantly young meditators of Rajneeshpuram as a sin-sick cult, and sought to dismantle the town they’d built.

So began a rapidly escalating cycle of tit-for-tat measures to (re)gain control of the land. As the Rajneeshi community grew, the residents of Antelope, aided by conservation groups and the state, sought to stop the expansion. Sheela countered by instructing some of the sannyasin to move into Antelope in sufficient numbers to outvote the town’s original residents. When a Rajneeshi hotel in Portland was bombed, sannyasin began patrolling the town with semi-automatic weapons. Then, in an attempt to win a county election, the commune bussed in homeless people from around the country to come live with them in order to swell the ranks of sympathetic voters. And when that didn’t work, a handful tried to incapacitate non-Rajneeshi voters by deliberately contaminating local restaurants with salmonella.

Despite this litany of chilling facts (and more that I won’t reveal for fear of being a spoiler), there are no unambiguous heroes or villains in the story. Sheela — scheming, caustic, and murderous — did what she did out of a genuine desire to protect the guru she loved and the community she led. As for the put-upon residents of Antelope, some seem to have been driven as much by bigotry as by environmental priorities. Though they didn’t all wear the same color clothing, like the sunnyasins they scorned, at least some of their actions were informed by religious fundamentalism and conformity in the name of individual freedom.

The show doesn’t conclude with a clear moral ... we are left to wrestle with the same issues as are making headlines today.

And what of the thousands of pilgrims who flocked to the Oregon wilderness to build homes, farmland, and pool their resources. Were they delusional? Self-indulgent? Perhaps. But it’s inescapably moving to witness their hunger to feel not just joyful, not even just accepted, but effectual. We see that same longing expressed today in the DIY lifestyle and political activism of a new generation that will inherit the consequences of their elders’ failures.

The show doesn’t conclude with a clear moral; there is no “takeaway” that we can tuck into a coupon drawer and forget about as we absorb the next cultural meme. Instead, we are left to wrestle with the same issues as are making headlines today.

What is our obligation to the “other” — whether it is a group of those fleeing oppression like the Central American immigrants camped on the California border or simply idealistic travelers running towards the vision of a loving, egalitarian society? Is democracy solely a matter of who gets the most votes, or is it also about protecting the minority against what John Adams called “the tyranny of the majority?” And above all, what is community? Is it the intentional aggregation of people who choose to cast their lot together, or is it the simple proximity of people who share a church, a coffee shop, and a common vision of who doesn’t belong?

The one clear answer to emerge from “Wild Wild Country” is that to be viable, a community cannot insist on homogeneity. A diversity of voices is needed for a community to thrive. Otherwise, we run the risk of all converging on the same note and holding it until our breath runs out.

Ranjeeshpuram was abandoned in 1985, and — in a classically American bit of irony — the Big Muddy ranch is now the property of Young Life, a Christian youth organization. While some former Rajneeshis look back at their time there with dismay, even astonishment, some featured in "Wild Wild Country" don’t. Their broken utopia was built in equal measure by the affluent and the alienated, by those rejecting mainstream society and those marginalized by it. There’s a rare, needed sort of democracy in that.