Advertisement

Commentary

The Royal Wedding Forces Britain To Confront Multiculturalism

Watching the wedding of Meghan and Harry early Saturday morning, I was reminded of a speech given by Robin Cook in 2001. Eager to promote a more inclusive, multicultural version of Britishness, Cook — then serving as U.K. foreign secretary — reminded his audiences that Chicken Tikka Masala was the most popular dish in Britain. For Cook, this was something to celebrate rather than bemoan.

As Cook put it, Chicken Tikka Masala was a hybrid dish — neither purely Indian nor purely British. “Chicken Tikka,” he explained, “is an Indian dish. The Masala sauce was added to satisfy the desire of British people to have their meat served in gravy.” But Cook did not stop there. He urged his audience to treat Chicken Tikka Masala as a lens for viewing the broader sweep of British history. “[I]t is a perfect illustration,” he said, “of the way Britain absorbs and adapts external influences.”

In the 17 years that have passed since Cook issued these remarks, his argument in praise of hybridity has been repeatedly put to the test. Yes, many Londoners seemed to embrace this cosmopolitan ethos. Walk down many streets in London today, after all, and you will find a striking array of peoples jostling up against (if not always exactly intermingling with) each other. This is the city depicted in the novels of writers Zadie Smith, Monica Ali and Hanif Kureishi. The city celebrated in movies such as “Bend it Like Beckham.” The city that elected Sadiq Khan — the son of Pakistani immigrants — as mayor in 2016.

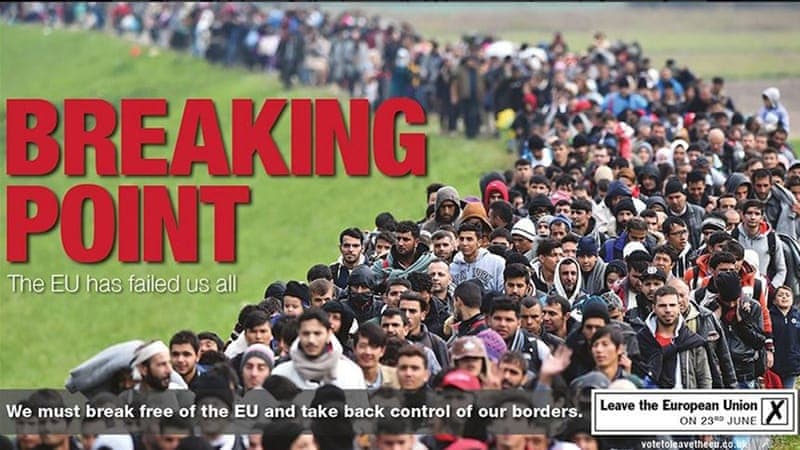

But the view from parts of rural Britain has always suggested a degree of resistance. It was in rural Britain that the British National Party, with its white nationalist and Euroskeptic messaging, was able to make some inroads during the 2000s by playing on citizens’ economic grievances. And where the right-wing UK Independence Party headed by Nigel Farage found its strongest supporters, leading to David Cameron’s fateful decision to hold a referendum on EU membership in June 2016. Anti-immigrant sentiment was at the heart of the “Leave” campaign. That sentiment came to the fore in one of the most controversial images issued by the campaign: an arresting photo of migrants and refugees on the march, with the words “Breaking Point” printed in red above their heads.

But this is not just a simple urban-rural divide.

We saw recently in the debacle over the government’s handling of the rights of the “Windrush generation” how those at the highest levels of power have sanctioned the unequal treatment of Caribbean immigrants, even those whose families have been in Britain for generations.

Moreover, some of Britain’s most popular cultural exports in recent years — "Downton Abbey," "Upstairs Downstairs," "The Crown," "Victoria," not to mention all of those films about 1940 and Winston Churchill — have also plied very traditional, and very white, understandings of Britishness. Indeed, their success may well partly turn on their narrow conceptions of what constitutes British culture. As the historian Yasmin Khan, author of "The Raj at War," complained of the film "Dunkirk," which overlooked South Asians’ participation in that heroic evacuation, “Britain didn’t fight World War II -- the British Empire did.”

It was this same narrowness that so irked the Jamaican-born scholar Stuart Hall. In one of his most stirring essays, published in 1991, he reminded his British audience that he “was the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea.” As Hall knew all too well, one didn’t need Chicken Tikka Masala to see that British culture was the product of intermixing. That intermixing was everywhere, the legacy of Britain’s centuries-long imperialist endeavors.

Some Britons may well be discomfited by this vision of their country. But ... if the new Duke and Duchess of Sussex have their way, they will have to confront it.

Both Cook and Hall — both sadly now dead — would, I think, have been delighted by the ceremony that took place in St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle on Saturday. For almost every aspect of the wedding of Harry and Meghan, from the detailing on Meghan’s wedding veil to the impassioned sermon delivered by the African-American Bishop Michael Curry to the inclusion of The Kingdom Choir and the cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason in the program, served as a reminder of Britain’s complex and vibrant multicultural history.

From start to finish, the ceremony echoed a point recently made by the Labour MP David Lammy in the House of Commons:

My ancestors were British subjects. But they were not British subjects because they came to Britain. They were British subjects because Britain came to them, took them across the Atlantic, colonised them, sold them into slavery, profited from their labour and made them British subjects. That is why I am here. That is why the Windrush generation are here.

Some Britons may well be discomfited by this vision of their country. But sooner or later, at least if the new Duke and Duchess of Sussex have their way, they will have to confront it.