Advertisement

Commentary

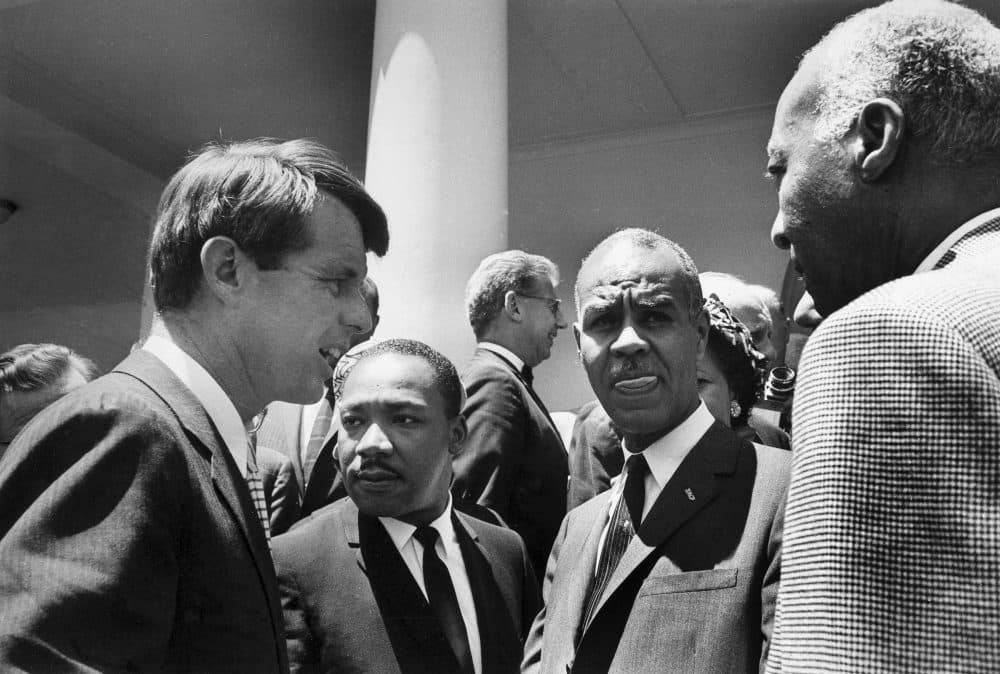

RFK's Capacity For Hope In Dark Times Still Inspires

This week marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy. The killing, coming as it did two months after that of Martin Luther King, Jr. felt not just heartbreaking, but apocalyptic and crushing. 1968 was a dark political time: two leaders murdered, our country split asunder by the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement, its cities burning up as rioters sought outlets for their hopeless rage.

If you were alive then — and young and impressionable — 1968 seared and shaped you. Both my work life and my politics have roots in the year’s traumas.

However, less predictably, those months also taught me that even the most terrible political events can lead to radical, positive societal transformations. My capacity for hope in dark times, so essential for survival now, was stirred by Bobby Kennedy and formed by the activism that accelerated for many of us after his death.

Kennedy inspired me because of the way he turned his grief at his brother John’s assassination into a drive for social change. The violent loss could have crushed him. Instead, his suffering gradually transformed him from a man who could be callow and harsh into someone more pensive, someone who seemed to feel compassion for the dispossessed, who wanted to improve their lot.

News stories spoke about his reading Greek tragedies, Shakespeare and poetry as part of his effort to find ways to bear his own anguish. (Apparently, Jackie Kennedy suggested that he could find solace in great books.)

By immersing himself in literature, and matching what he found within its narratives to what he felt in his own heart, he seemed to have learned — or learned more vividly and meaningfully — that life is tragic. What had happened to him had happened to others; neither his horror nor his own failings were new; his fate was human.

Perhaps he also had opportunity — contemplating all those flawed, bold leaders offered up by Aeschylus and Shakespeare — to understand different perspectives on power and to consider more creatively how it could be used on behalf of those who suffered most.

When he campaigned for the presidential nomination, Kennedy used literature to energize his crowds. In his speeches he often quoted a line of Tennyson’s poem "Ulysses":

Come my friends, tis not to late to seek a newer world.

If you know the poem, you know that Tennyson’s Ulysses is a deeply restless aging man, who, finally returned from Troy, finds life dull at home and rallies his mariners to voyage again. He seeks to sail beyond the edge of the world into the unknown:

Death closes all, but something ere the end, some noble work of note may yet be done.

This Ulysses feels alive only when in full motion and seeking glory. He is drawn from Dante — by whose account the ocean voyage ends tragically, the hero and his sailors drowned. Some people believed that the violent deaths of two brothers had left Kennedy unconsciously courting death. Who can know. Yet perhaps the ambiguous poem lived within him with two meanings, one public and rallying, the other more fatalistic and streaked with doom.

... the message Bobby Kennedy’s run for office offered was that you could be distraught and yet you could find purpose and continue.

Yet however complex his motives and his affinity for the writers he came to savor (his contemporaries recalled that he carried a book in his pocket — so he could read whenever a moment opened up), the message Bobby Kennedy’s run for office offered was that you could be distraught and yet you could find purpose and continue.

The hope he offered made his assassination more devastating. Yet it turned many of us into more committed social activists (and some of us into even more ardent lovers of literature).

What’s important to recall now is that our despair and fury in 1968 helped generate powerful social movements that improved much about American life.

First were the protests that successfully pressured Nixon to end the Vietnam War. A few years later the same energy morphed into a women’s movement that pushed hard and with remarkable effect for women’s equality. If you are a woman and can play team sports, join the Army, become a partner in a law firm, a professor in a university, an astronaut, an engineer, a newspaper editor, a movie producer or a plumber — or if you can find daycare for your child, or get health care from a female doctor, or vote for a woman senator (to name a few rare-before-1972-opportunities among many) you can thank the Feminist movement.

So too, the Stonewall riots in the summer of 1969 began the long battle for LGBTQ rights. And with that battle, the new possibility for people of all sexual orientations and gender identities to begin to live full lives in the open. Only thanks to political activism did our homophobic government finally cough up money for the research that gradually turned HIV from a complete death sentence into — for those with access to the new medicines — an almost manageable ongoing condition. Eventually, gay marriage, too, became possible.

All three movements took deep inspiration and many practical lessons from the Civil Rights Movement; all four are imperfect, unfinished and always in danger of backsliding.

Yet, if we can appreciate all that protest and organizing really did accomplish it will remind us what it means in hard political times, as Tennyson writes:

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.