Advertisement

Commentary

The Partisan Divide Is Eroding Public Confidence In The Supreme Court

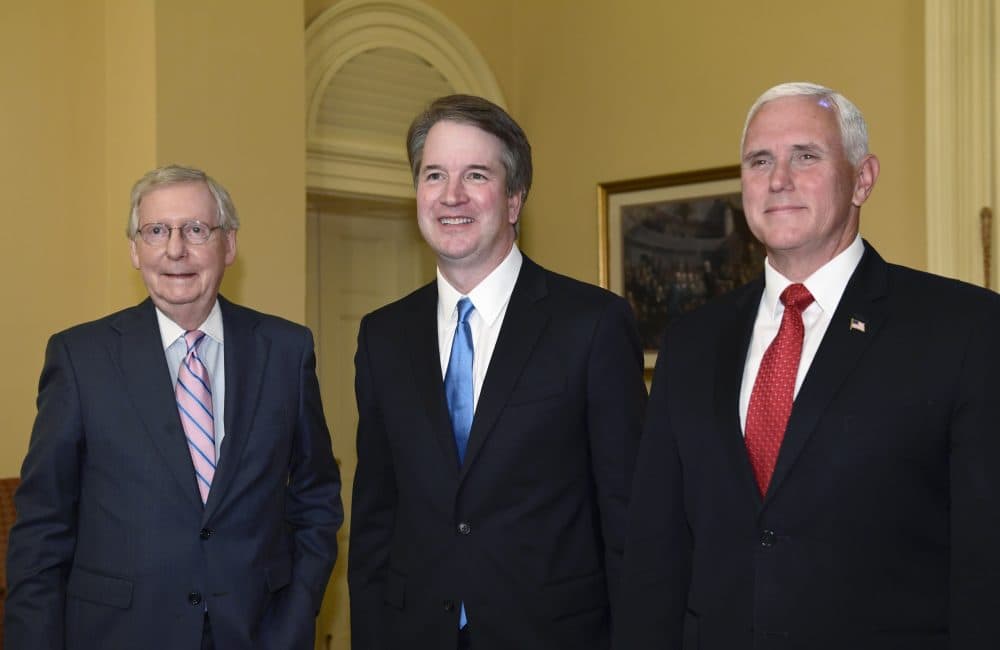

The retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy and the nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh have triggered predictable expressions of jubilation and despair, depending which side of the national divide you favor. Never, it seems, has the Supreme Court been as politicized, and behaved so unlike a genuine court, as today. For this same reason however, much of the extensive reaction is overstated. In the longer run the continuing partisan manipulation of appointments will likely undermine the very impact on lasting jurisprudence that it seeks to create.

Courts, and especially the Supreme Court, derive authority from their status as neutral, disinterested guardians of our social compact. Despite repeated evidence to the contrary, we expect more from our judges than from elected politicians. An expectation of civic virtue attaches to the robe.

When courts behave like political bodies, their decisions acquire the shelf life of political pronouncements. Adjudication of constitutional law is reduced to the level of an executive order or a congressional enactment, and is as easily repealed or amended. For this reason judges are obliged to separate themselves from popular passion and political ideology. But the Roberts Court consistently fails to do so. Some examples:

When courts behave like political bodies, their decisions acquire the shelf life of political pronouncements.

Precedent: We need courts to bring predictability to the rules we must obey. Supreme Court Justices have a heavier burden than other judges to exercise self-discipline and observe precedent, because they enjoy unsupervised power to reverse their own decisions.

Just last month the Court reversed a long-standing approach to the First Amendment’s role in labor union activity. In Janus v AFSCME Council 31, the Court ruled that requiring non-member public employees to contribute to union coffers although they benefit from union bargaining is unconstitutional. While there are arguments to be made on either side of this issue, it was decided long ago. In 1977, in Abood v Detroit Board of Education, the Court decreed that mandatory contributions to a union conferring benefits on all employees implicated no First Amendment rights because they did not “force ideological conformity or otherwise impair the free expression of ideas.”

Justice Kagan’s dissent castigates the Janus majority decision because it “subverts all known principles” of precedent. She is correct.

Intellectual honesty: Real courts confine themselves to legal analysis; it is the height of unprofessionalism for judges to write decisions “backwards,” starting with the result. But in a linguistic poster child for ignoring both precedent and proper analysis to reach a desired result, Antonin Scalia effectively removed language from the Second Amendment to invalidate restrictions on personal gun ownership. In 2008, in District of Columbia v Heller, the Court reversed 75 years of precedent in the service of a national obsession with firearms that had developed in the intervening half century. Since 1934 when the National Firearms Act (supported by, among others, the National Rifle Association) was enacted to limit access to machine guns, restrictions on personal weaponry were not in legal (or popular) dispute. Former Chief Justice Warren Burger rightly described the rationale of the Heller decision as “a fraud on the American public.”

Ethics: We expect judges to conduct themselves according to a code of ethics. But the Justices have never adopted one, and they regularly flout ethical norms. Justice Scalia went duck hunting with Vice President Dick Cheney while the Supreme Court was hearing a case in which Cheney was the defendant. During the 2016 presidential campaign Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg publicly described Donald Trump as a “faker.” Neil Gorsuch is not the first Justice to appear before the partisan Federalist Society, but he is the only one to have been celebrated in this manner at the Trump International Hotel in Washington D.C. Every other court in the land explicitly prohibits such behavior.

Disinterested adjudication: The role of courts, based on neutrality, is decidedly not to search for issues on which judges would like to offer their opinion. Judges are in business to adjudicate the issues raised by litigants. Our adversary system is based on the principle that opposing parties ensure good results by presenting arguments on each side of an issue.

Instead, in possibly the most consequential decision of the modern era, Citizens United v Federal Election Commission, the Court rejected the case brought to it by the parties, and substituted its own. Originally the appeal involved a narrow question: Did the language of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law apply to a 90-minute documentary in the same way that it regulated the use of television commercials? Whatever answer the court might have provided to that issue did not require grandiose pronouncements on corporate personhood or on the equivalence of money to constitutionally protected speech. Instead, in the middle of oral argument, the court ordered the parties to submit briefs on these questions, and thereafter conducted another hearing on the issues the court wished to consider.

Which brings us back to Anthony Kennedy, who authored Citizens United. Notwithstanding the general reaction, his retirement, even during a Trump presidency, is not a sea change meriting excessive jubilation or despair. Realistically, Judge Kavanaugh could well have authored the same opinion. Whether he would have done so or not, the real reason for dejection is that he will be joining a partisan political body. The Court is intended to provide long-term stability and fairness to our Constitutional framework; it cannot do so if its rulings, like those of the other two branches, are no more than a consequence of the changing winds of political fortune.