Advertisement

Commentary

We Need To Start Taking Voting Rights Seriously

The whole universe seemingly fixated last week on Elizabeth Warren’s Native American ancestry. Given that we’re talking one person who never benefited professionally from listing herself as a Cherokee descendant, this is a sideshow to what is a real concern:

Native Americans are being disenfranchised, in at least one state. And that reflects a broader denial of voting rights in America, two weeks before the midterms.

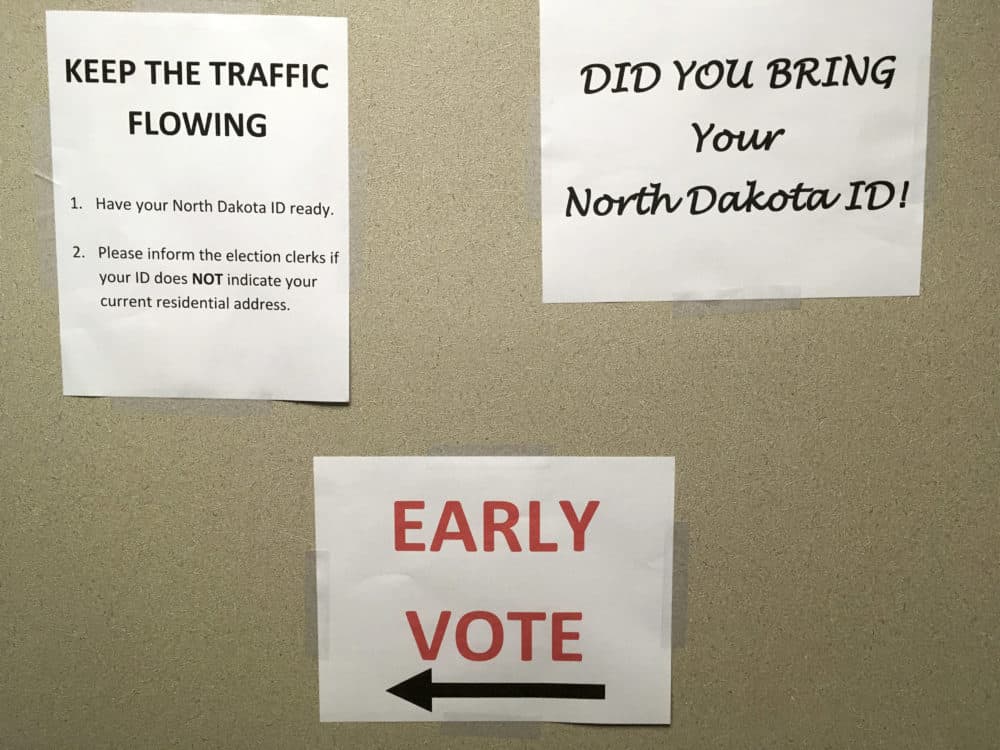

As Natives were the first Americans, let’s deal with their story first. North Dakota, using a law recently upheld by the Supreme Court, requires its residents to list a street address on their identification to be eligible to vote. Many of North Dakota’s 27,000 eligible Native American voters, living on reservations, have P.O. boxes for addresses, rather than streets, raising the specter that they’ll be barred at the polls from casting ballots.

The absence of street addresses isn’t due to plains geography. Rather, when the federal government first herded people onto reservations, they “weren’t meant to be homesteads. They were meant to be prisons,” Randall Akee, a UCLA professor of American Indian studies and public policy, said in a Brookings Institution podcast. “There’s no need for addresses in a prison, obviously.”

The politically informed will have noted the partisan significance of North Dakota’s law. “American Indians tend to vote Democratic,” Akee says, and the state’s Democratic senator, Heidi Heitkamp, is in a tough re-election fight. She won six years ago by 3,000 votes, a fact that mathematically empowers Native Americans to be her potential life preserver this year as she struggles in politically turbulent seas. (Donald Trump carried North Dakota in 2016 in a landslide, and Heitkamp just voted against his Supreme Court nominee, Brett Kavanaugh.)

Of course, the real objection to the disenfranchisement isn’t partisan but principled: Having killed or stolen land from the first Americans in the 19th century, we are perpetuating injustice with technical barriers to their right to vote in the 21st. Nor is this a stray example: The plot, as they say, thickens when you look around the country, speckled with similar efforts at shrinking the supply of eligible voters.

Advertisement

It’s true that Florida’s convicted felons aren’t as sympathetic a group as long-suffering Native Americans. But you might think again when you hear some of the reasons that Gov. Rick Scott and his cabinet adduce during their regular consideration of restoring the franchise to a handful of those felons.

In June, one cabinet member asked an African-American man how many children he’d fathered by how many women. Now, irresponsible promiscuity casts human wreckage in its wake, and it should carry consequences. Enforced child support is one. Denial of the right to vote is not. Indeed, most states restore civil rights like voting to felons once they’ve paid their debt to society.

Next month, Florida votes on a constitutional amendment to automatically restore rights to certain felons. The result, of course, won’t affect other jurisdictions that have busily pruned their voting lists since a 2013 SCOTUS reversal of federal approval before places with histories of racial discrimination change voting policy.

Of course, the real objection to the disenfranchisement isn’t partisan but principled...

States, mostly southern, used the decision to strip voters from their rolls.

While there’s little to be done for this year’s vote, the advocate in that previous link suggests states’ voters combat disenfranchisement by supporting things like automatic voter registration (Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker signed such a bill this year, to take effect in 2020).

That’s a reasonable solution and more achievable than Maine’s and Vermont’s approach of not disenfranchising felons at all, which surely would be a tough sell for some states’ political cultures. Even Florida’s ballot question would withhold rights from those who committed the most heinous crimes, such as murder and sex offenses.

Automatic registration would put the franchise in the hands of the law, rather than lawmakers. Perhaps you think I’m being unduly cynical about the intentions of our elected politicians? It’s not as if they’d connive to, say, steal a Supreme Court seat and then ram through a questionable nominee of their own, right?

Right?