Advertisement

Commentary

My son’s a college sophomore, and I’m still learning how to be a dad

I was talking to a fellow dad the other day, the two of us sharing a beer on the porch. “Do you think it’s more sad or weird when a kid leaves home?” my friend asked.

I thought for a moment. My son Hardy recently finished his freshman year of college and turned 19 on Aug. 1. In the last year I can count on my fingers the number of times I have seen him, unlike the previous 18 years of his life, when all I did was see him.

“I have to admit, I think about the dog more often now than my son,” I said to my friend.

“Weird,” my friend said.

“Really weird,” I said.

Not knowing what else to say, my friend and I shrugged our shoulders, finished our beers and parted ways for the evening — another fatherly moment for the record books.

Tossed in with the big changes to our lives was this change of wardrobe, from choosing how I wanted to look each day to opting for battlefield dress.

But I could have one-upped my weirdness by pointing out to my friend that the nondescript T-shirt I was wearing was exactly 19 years old, purchased at the time of Hardy’s birth. I was a first-time parent and a stay-at-home dad, my wife Cathlin heading off to work each morning while I tried to figure out what to do all day with this new person in my life. Tossed in with the big changes to our lives was this change of wardrobe, from choosing how I wanted to look each day to opting for battlefield dress.

I purchased four T-shirts, two black and two gray, that required no forethought each morning and could stand up to all manner of food splatter and spit-ups, playground dirt and grime, along with the metaphorical messes of joy and humiliation. I wore those T-shirts every day those first few years. They were my armor and my routine and I have often thought, after those early days of parenting had ended, that I should frame them, encase them in glass with wood borders and hang them in various rooms around the house to remind me how parenting can often feel like reaching out and grabbing onto any mundane life raft and holding on for dear life.

Instead, I have taken to wearing them again, unearthing the T-shirts from a spot deep in the closet where they have been in hibernation, waiting, I suppose, for the right moment to awaken, which happens to be now. Wearing them brings back feelings and moments I had nearly forgotten.

Hardy was a horrible sleeper as an infant and toddler and I began wearing the T-shirts late at night too, shuffling about the house with him as he fussed. Eventually, I discovered a way to soothe him, or rather soothe the both of us: watching "The Wire" together, a five-season wonder about drug dealing in Baltimore.

Some may wonder about my watching a show that depicted so much violence with my infant son and cry foul at my parenting skills. But again, so much about parenting means grabbing onto whatever is nearby.

As a stay-at-home dad, my only friends, it seemed, had become the moms and nannies at the park. This journey at night with Hardy and the men and women of "The Wire" was for me another friendship, a truly disparate group of people who were dear to me, even though they had no idea I existed.

Eventually, I discovered a way to soothe him, or rather soothe the both of us: watching "The Wire" together, a five-season wonder about drug dealing in Baltimore.

Years later, after we had moved from New York City to Martha's Vineyard, I was standing in the pizza line at Giordano’s. It was early evening and Hardy, now 8 years old, was with me, along with his 4-year-old sister Pickle, a nickname that arrived when she was in the womb and never left.

As I waited with my children, I noticed a man watching me. He was a hard-looking man giving me a hard look. He stood and he stared and I wondered if I was about to be attacked, and whether I should turn and run with my children or stand my ground and hope my atrophied college wrestling skills were not as rusty as I feared they had become.

The man moved toward me and I crouched, ready to receive and defend whatever was coming my way. But then he leaned in close and said: “Are you McNulty, from 'The Wire?' I keep thinking yes and then no, so I had to ask.”

I sighed with relief and smiled with gratitude at the man. McNulty was one of the stars of the show, a cop forever getting into trouble through sleeping around and too much drink. I told the man that I was not McNulty but thanked him for the compliment. We shook hands and reminisced about the show, something I now do with Hardy. We watched it together when he turned 13 and I had taken it upon myself to educate him on the great movies and television shows of earlier eras. While watching the show I reminded Hardy of the moment at Giordano’s. He looked at me and laughed.

“Dad, you look nothing like McNulty. That actor is actually good looking.”

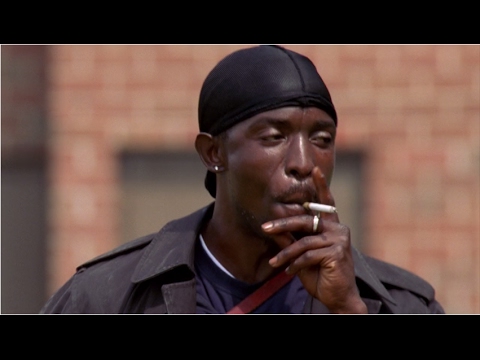

A few years later, Hardy and I watched the show again when Michael K. Williams died, to pay tribute to the brilliant actor who played Omar.

But why these two talismans now, a T-shirt and a television show? There are so many roads I could be traveling down as I think about my son’s birthday, but it is often the small bits and pieces that stick out, standing the test of time by returning again and again, that remind me what it means to be a father.

For the entirety of my children’s lives I have written about them, putting words and emotions to moments both small and large. Recently I published a book of these essays, and during a question and answer period at a reading, someone asked me what I had learned from the experience.

The question stopped me in its enormity. I tried to answer but at first mostly stumbled about, talking about the importance of paying attention.

But then it hit me. Parenting had taught me how to feel a fuller spectrum of emotions, from love to rage, from grief to worry to ecstatic joy and back again. And writing about these experiences had reinforced how much I wanted to feel, to sit with these emotions and become more alive than ever before.

Which makes it so much more confusing when a child leaves home. I was prepared to feel sad saying goodbye at college drop-off, and to avoid Hardy’s empty room upon returning home. What I did not see coming, however, was a loss of feeling as the weeks turned to months. To go from spending every day thinking about a child’s needs and desires to stepping back and marveling at their independence is both gratifying and depressing. It is, of course, the evolution of things, the parent-child relationship moving into a new chapter I am not yet fully conscious of, but that doesn’t make it any easier.

Parenting had taught me how to feel a fuller spectrum of emotions, from love to rage, from grief to worry to ecstatic joy and back again.

But then recently Hardy called home to check in with me.

After I hung up, Cathlin asked me how he was doing.

“I don’t know,” I said. “He called to see how I was doing, to ask what I had been up to.”

“That’s all?”

“Yes, that’s all.”

It felt as if I had been talking to a friend I had not seen in awhile and missed dearly, and who missed me too. It felt as if I was talking to someone who on the cusp of his birthday had given me a gift instead of the other way around — the gift of feeling in a new way I was just beginning to understand.

In return I wrapped up one of my old T-shirts and gave it to Hardy on his birthday. I am sure McNulty would approve.