Advertisement

Commentary

A letter, a flag, a Spider Man keychain: the relics first-year college students carry from home

Every fall for last 20 years or so, I’ve had the privilege of teaching a dozen first-year college students. I meet them as they begin the transition to college from homes literally all over the world — as far as Singapore, as large as a major Greek metropolis, as small as a tiny Ohio town (pop. 45), and as nearby as Lexington, Mass.

I teach a small seminar about psychiatry and the lived experience of mental illness. The first week, when the students are still settling into their dorm rooms, learning their way around the cafeteria and adjusting to having roommates, we learn about the concept of attachment, the sense of responsive, attuned connection between a caretaker and a child.

We discuss how the need to be connected is critical for all of us. It begins in early childhood, when secure attachment — the sense of being seen, soothed when sad or frightened, and feeling safe and protected within a relationship — directly shapes the architecture of the brain and builds our capacity to learn, be flexible and resilient. It’s always my hope that my seminar can provide a similar kind of connection by creating a community of learners; a safe harbor during this sometimes challenging transition.

We begin class by discussing two of my favorite pieces of writing, academic and otherwise. In “Ghosts in the Nursery,” psychoanalyst Selma Fraiberg and her colleagues explore the question of why a family taking care of their baby can't hear her cry. It’s a clinical analysis of how to support parents who are struggling to meet the needs of their children, and it gives my students a window into the thought process and decisions of a caring therapist. The treatment captures the urgency to intervene and also how key it is to bear witness to the parents' pain — to build their capacity to respond to their children.

What are these objects, sometimes taking up valuable suitcase space on a student’s first-ever trip to the U.S.?

In “I Stand Here Ironing,” a short story by Tillie Olsen — a real writer's writer — the narrator (the mother) laments the obstacles to giving her child what she needs to feel nurtured, while also sharing her pride.

The mother in this story longs, profoundly, to connect with her daughter, and is ashamed about missing opportunities to do so. The story also embeds the an understanding of mental illness in the context of systemic inequities.

It’s exhilarating to hear my students’ reflections on this work. But it’s always the last moments of the class that stay with me. I ask them to bring an object to the seminar — something meaningful they’ve brought with them from home, and that offers them comfort during the transition to college.

What are these objects, sometimes taking up valuable suitcase space on a student’s first-ever trip to the U.S.? My students this year gave me permission to share the stories they told each other.

One student carried a letter from a seventh-grade teacher. He explained that he’d been a mediocre student until middle school, when he started staying after class, to get extra help and also extra time away from the chaos of his home life. His teacher leaned over one day and whispered, “You should go for valedictorian.” That small moment motivated him deeply. Five years later, he graduated as valedictorian.

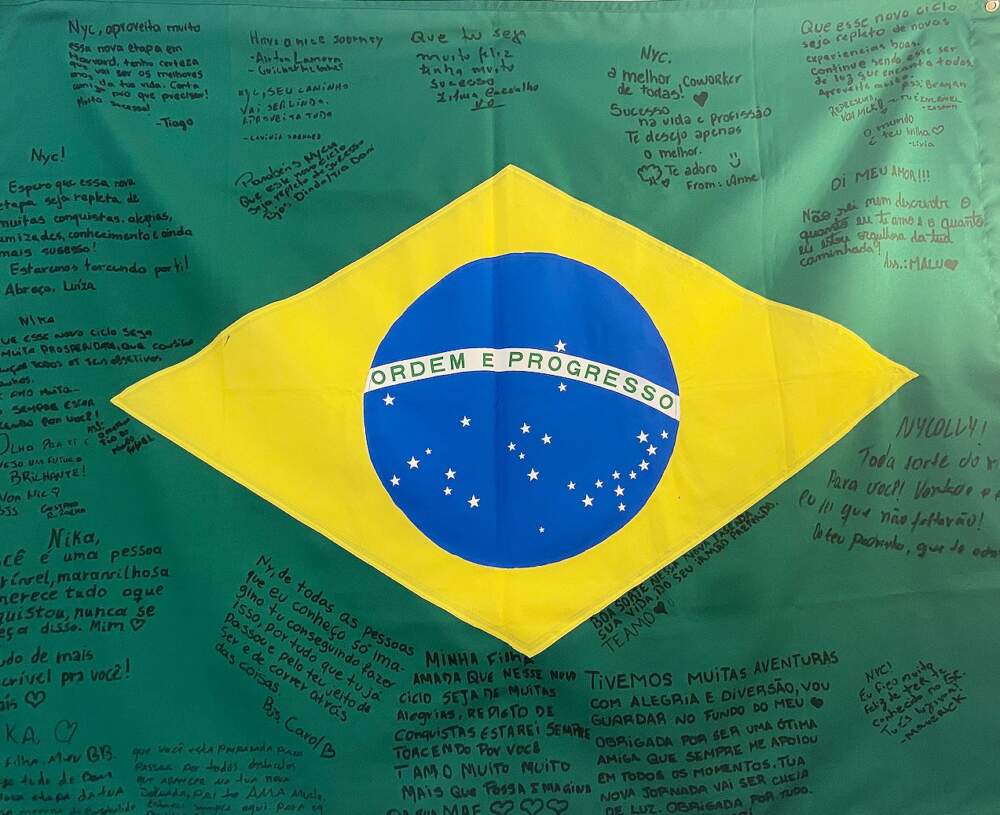

Another student brought a flag. She’s from Brazil, and her friends and family signed a Brazilian flag that now hangs in her dorm room.

Another brought a photo of herself, as a toddler, feeding the ducks with her grandmother, who’d lived with her family and cared for her while her parents trained to become doctors.

Another student, from India, brought a Spiderman keychain. When he left home, he told his mom that, like Spiderman, he’d swing from one building to another while in college, but eventually swing back home to her. He FaceTimes his family every day, despite the time difference.

If I'd been asked that question during my first year, I might haves said my tattered blanket, one of the few objects I have from when I was a small child. It has meaning because my mother died when I was 4 years old.

I thought about what a colleague once told me about mentoring young people -- how meaningful it is to put fuel in a rocket.

This year, for the first time, I also asked my students to tell me what advice they might give their parents. Too often adults approach young people with the attitude: I know you don’t know. But this new crop of first-years were in high school during the pandemic (some of my students did two full years of “virtual” high school). They weathered the public health emergency, and its accompanying crisis of uncertainty, with their parents. I imagined they’d have some valuable observations to share.

The question made most of them pause. I got responses like “that is an interesting question” or “let me think about that for a moment,” but ultimately, they delivered.

Don’t make your trauma your child’s trauma, they told me. (That’s certainly an aspiration I’ve had and the theme of “Ghosts in the Nursery.”) Another student wanted her parents to take care of themselves. She explained that raising children requires subjugating your own needs and desires, so it seemed her parents ought to just enjoy life. Another beseeched his mom and dad to trust their good work in raising an independent person. Trust me, he said.

Their responses make me think they’ll be open to discovering that people with mental illness are often incredibly courageous and can teach us so much.

After teaching my first class of the semester, I went for a run along the winding Charles River. I thought about what a colleague once told me about mentoring young people — how meaningful it is to put fuel in a rocket. When we teach, we have the blessing to learn with our students and invest in a promising future.

No matter that my students may face obstacles, disappointments, and challenges, I want to tell their parents: They are launched.