Advertisement

Commentary

You can’t be a truth-teller when you deal in willful lies

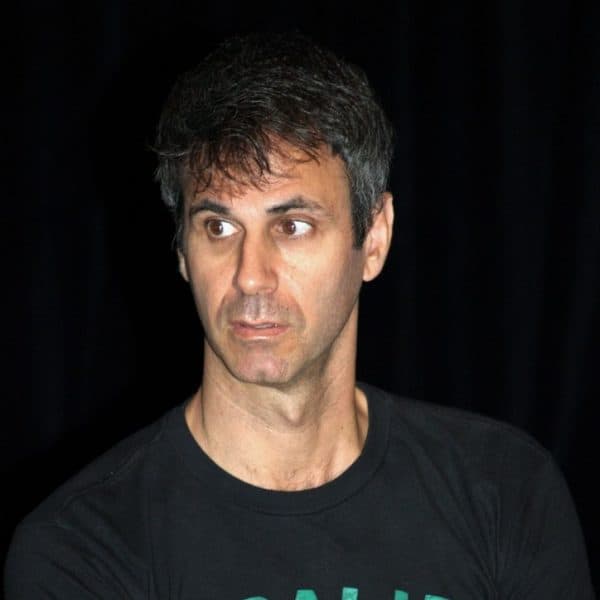

Like a lot of other stand-up comedy stans, I’ve tracked the ascent of Hasan Minhaj with an admiration approaching awe. His Netflix series, “The Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj,” was perhaps the sharpest of the various Daily Show spinoffs, and his Netflix comedy specials were even better.

The 37-year-old has a frenetic manner and a knack for welding whip-smart jokes to piercing social commentary. As an Indian-American Muslim who came of age in the wake of 9/11, Minhaj focuses on the fierce ambitions and anxieties that drive the children of immigrants, as well as the bigotry they inevitably endure.

What’s most remarkable about his shows is his ability to shift from breezy riffs to moments of mic-drop sincerity in the space of a few seconds.

Alas, it turns out that many of the most poignant moments in his routines are flat-out fictions. They never happened.

In 2017’s "Homecoming King," for instance, he tells the story of showing up at the home of the girl he expected to take to prom, only to find another guy putting a corsage on her wrist. The girl’s mother explains that they don’t want their daughter to appear in pictures with a brown boy, for fear of what the relatives would think. “I’d eaten off their plates,” Minhaj tells a hushed audience. “I’d kissed their daughter. I didn’t know that people could be bigoted even as they were smiling at you.”

The tales he tells in "The King’s Jester," released last year, are even more dramatic. He relays the saga of his mosque being infiltrated by an undercover agent and eventually having his head slammed against the hood of a cop car, as a suspected terrorist.

Later, because of his penchant for publicly provoking despots, he receives an envelope with a white powder inside, which he mistakenly spills onto his young daughter, necessitating a panic-stricken trip to the ER.

In each of these moments, Minhaj is no longer cracking jokes. He is confiding painful personal experiences to an audience hanging on his every word.

And he made them all up.

Minhaj admitted as much to Clare Malone, a New Yorker writer who documented his lies. “Every story in my style is built around a seed of truth,” Hasan explained. “My comedy Arnold Palmer is 70% emotional truth — this happened — and then 30% hyperbole, exaggeration, fiction.”

To those of us in the literary world, that phrase, “emotional truth” has an eerily familiar ring to it. It was the same expression James Frey used back in 2006, when he went on Larry King Live to defend his best-selling memoir, “A Million Little Pieces,” after it was revealed that he had fabricated many of the stories in that book.

“I hope the emotional truth of the book resonates with [my readers],” Frey said, adding, “It’s a memoir. It’s an imperfect animal. I don’t think it should be held up and scrutinized the way a perfect nonfiction document should be, or a newspaper article.”

That’s basically the defense that Minhaj is using: Hey, it’s a comedy routine. I’m not manipulating my audience by lying to them, because they’re coming for the emotional roller-coaster ride.

This argument is nonsense. It was nonsense when James Frey used it. And it’s nonsense when Hasan Minhaj uses it.

Worse than that: it’s dangerous nonsense.

Why? Because we’re living in an era, and in a country, where inflammatory lies have become the coin of the realm. These lies are precisely what drive the powerful algorithms that keep us addicted to social media, and what fuel the demagogues and would-be autocrats who have polluted our civic and political discourse.

In every case, the root cause is the same: willful deceptions intended to make us frightened, upset, and aggrieved.

This argument is nonsense. It was nonsense when James Frey used it. And it’s nonsense when Hasan Minhaj uses it.

I understand the argument Minhaj makes to justify his fabrications. He told them to bring attention to broader moral problems, such as racism, inequality, and the corruption of authoritarian leaders.

But Minhaj could have done that without exaggerating his own victimhood (or that of his family). And without vilifying people such as the teenage girl who refused to go to prom with him. Because of his decision to speak about her, and to post images of her during his show, that woman and her family have been publicly slandered and harassed.

As a writer of books that contain elements of memoir, I certainly understand the temptation to gin up our life stories. As a teacher, I hear from students all the time who worry that their lives aren’t “dramatic” enough to earn the reader’s undivided attention.

But what matters in the realm of storytelling isn’t the quality of the life being chronicled, but the quality of attention that is paid to that life. Because every single human being — from the rock star to the monk — is leading a life of tremendous upheaval, of transcendent joy and piercing sorrow. To focus only on those who suffer some garish form of trauma is, ultimately, to adopt the tabloid mindset.

True artists, of whatever variety, don’t rely on shock and awe, but the subtle and immense power of insight, compassion, sustained attention.

Simply put: You can’t be a truth-teller when you deal in willful lies.

Minhaj himself knows this. “I want to perform for reasonable people,” he tells the crowd, toward the end of The King’s Jester. “I want to be able to switch between satire and sincerity and trust that you know the difference. Everything here tonight is built on trust.”

When Minhaj tells a bunch of reasonable people that he feared he spilled anthrax on his daughter’s cheek, and they gasp in astonishment, that is not satire, or exaggerating for comic effect, or reaching for some emotional truth. It’s lying.

Our greatest comic minds — from Aristophanes and Mark Twain to Trevor Noah — have endured not just because of their prodigious wits, but because they are so courageous in their pursuit of the truth.

Minhaj should stop making excuses and apologize to his fans for violating their trust.