Advertisement

Commentary

A 1989 statute prevents Supreme Court justices from accepting honoraria. Justice Thomas found a workaround

In 2000, a rider was attached to an appropriation bill without much fanfare. The rider would allow federal judges to earn money — called “honoraria” — for speeches, supplementing their public salary. According to two reporters, Tony Mauro and Sam Loewenberg, some on Capitol Hill called that proposal the “Keep Scalia on the Court” bill because Justice Antonin Scalia had complained about how much more money he could have earned as a lawyer in private practice as compared to a justice (though he strenuously denied that he was contemplating leaving because he wasn’t being paid enough in a letter to the editor published by the Legal Times).

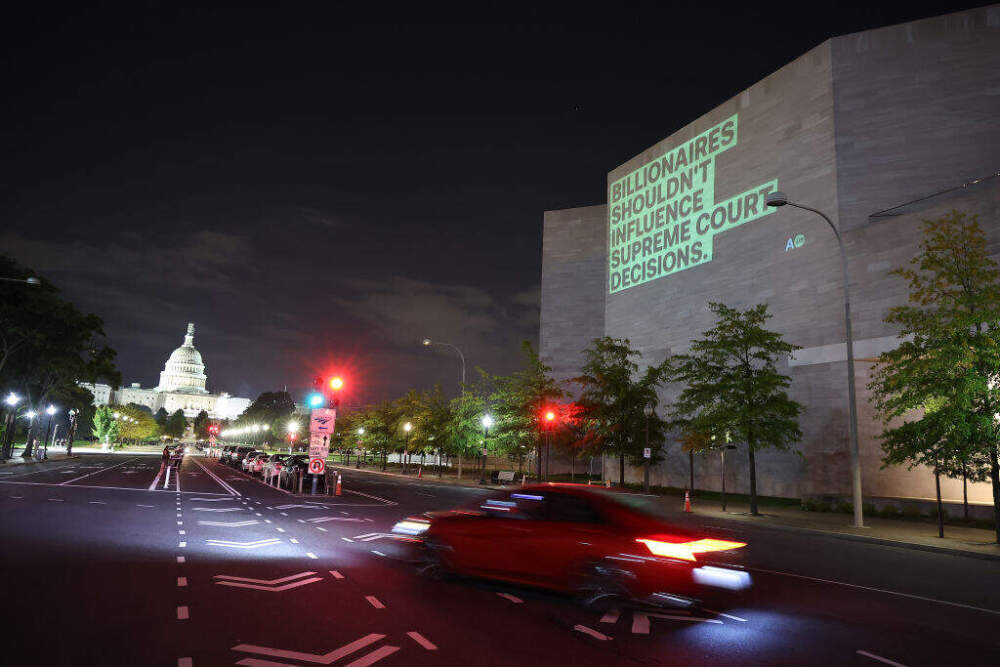

Judges had been prohibited from receiving honoraria or any other gifts since the Ethics Reform Act of 1989. The statutory ban covered all judges, members of the Supreme Court and district judges, like me. When I gave speeches in China, or Vietnam, or Italy, organized by law schools, I was barred from receiving any compensation for it. The statute’s proponents were concerned that private benefactors might influence official decision-making or, at least, give the appearance of doing so. One congressman equated receipt of an honorarium with “legalized bribery.”

Leading the charge against repealing the ban in 2000 was then-Sen. Russ Feingold (D-WI) who asked: “Are Americans comfortable allowing federal judges to accept $1,000, $5,000 or $10,000 speaking fees from corporations and other wealthy interests that may have cases pending in the federal court?” After a public outcry, the proposal was defeated.

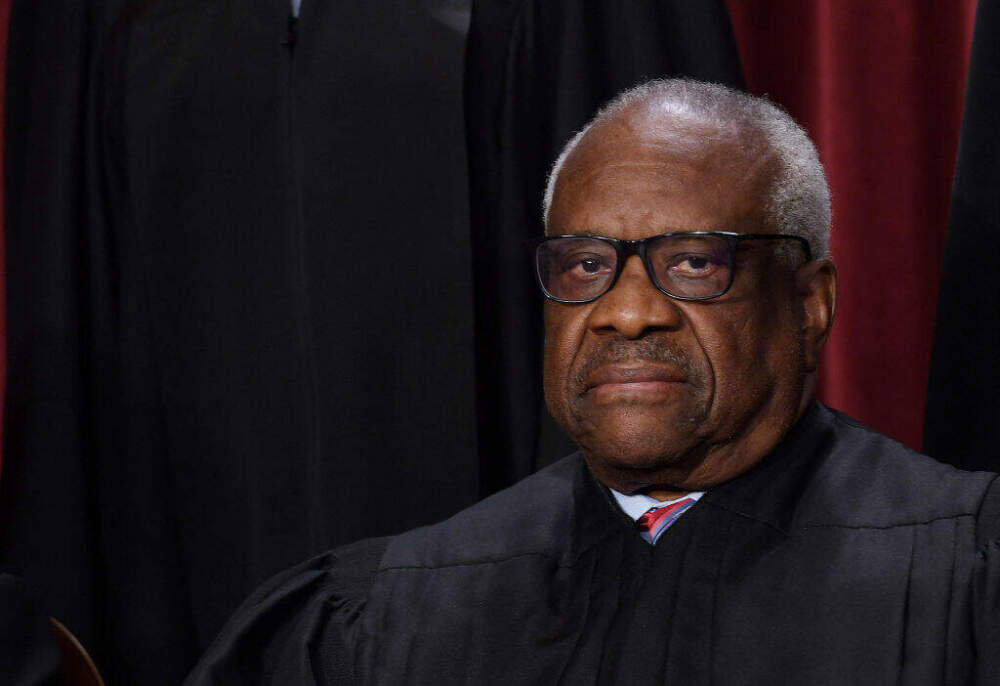

But Leonard Leo, the man largely responsible for building the conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court and filling the lower courts with Federalist Society judges, figured out a way around the statute.

According to ProPublica, George Conway, a conservative lawyer (now a “Never Trumper”) said that Leo “saw it as his responsibility to help take care of judges even after they had made it to the highest court in the country.” Conway is quoted, saying: “There was always a concern that Scalia or Thomas would say, ‘F--- it,’ and quit the job and go make way more money at Jones Day or somewhere else.” Leo wanted to keep them happy so they would stay.

I call Leo’s work the “Keep Justice Thomas on the Court” campaign.

Leo’s efforts to keep Thomas happy meant 38 destination vacations, a voyage on a yacht around the Bahamas, 26 private jet flights (plus eight by helicopter), a dozen VIP passes to professional and college sporting events (typically sitting in a box), two stays at luxury resorts in Florida and Jamaica, and a standing invitation to an exclusive golf club overlooking the Atlantic coast. Most of these were arranged by Leo and paid for by conservative billionaires.

While recent debates center on enacting an ethics code for the Supreme Court, the statutory honoraria ban has been in place for decades. No new ethical rules need to be promulgated, or codes enacted on this subject. It exists right now, as it has since 1989. But Thomas and Leo are doing an end run around it, accomplishing indirectly what the law prohibits them from doing directly. And no one is stopping them.

Amtrak was good enough for me and every other judge I invited to my Yale Law School class.

In effect, Thomas is saying, No, I may not take a fee for speaking at a dinner sponsored by the Koch brothers; heaven forbid I violate the 1989 honorarium ban! But of course: Nothing stops you, Koch brothers, from lavishing me with a trip to Palm Springs in a private plane, sumptuous accommodations, and fabulous meals, as ProPublica reported he received. According to Leo and Thomas, there is nothing wrong with conservative billionaires enabling Thomas to have a lifestyle far beyond what his judicial salary allows.

If history is any indication, the version of Congress we had 23 years ago might have gone ballistic in response to recent discoveries about Thomas. If they were concerned about federal judges getting money for honoraria, they surely would’ve been concerned about judges evading the honoraria ban with luxury vacations. If they were worried about rich benefactors paying judges for their speeches, they would surely be concerned about rich benefactors providing judges with private planes and high-end accommodations. But this time, unlike 1989, Thomas and Leo didn’t bother to ask.

Consider that Thomas just didn’t bother to disclose any of it. It took investigative reporters to find out the scope of his lavish lifestyle, and the conservative benefactors who supported it.

True, travel expenses, defined in the statute as those that are “actual and necessary” are excluded from the honorarium ban. A private Gulfstream jet was apparently “necessary” to get Thomas to speak at the Koch brothers’ dinner (a speech that is itself problematic, if it was a fundraiser and Thomas the draw.) The federal judges I know travelled economy. What about the private jet to speak at Yale Law School in New Haven? Amtrak was good enough for me and every other judge I invited to my Yale Law School class.

Ordinary (non Supreme Court) judges are bound by ethical rules that clarify what “actual and necessary travel expenses” entail, although I would be surprised if other judges needed the clarification. Those rules provide that a judge may accept reimbursement limited to the “actual cost of travel, food and lodging reasonably incurred by the judge.” Anything above that amount is considered “compensation,” which is barred (and of course, those rules already prohibit judges from associating themselves with entities that are publicly identified with controversial legal, social, or political positions, like the Kochs.)

These ethical rules don’t bind the Supreme Court. Not even the statute that’s been on the books since 1989 seems to hold sway anymore.

In 2000, then Chief Justice William Rehnquist, assured the public in his year-end report on the federal judiciary that “any honoraria would be governed by the strict standards of the Code of Conduct for United States Judges.”

Oh, really?