Advertisement

Commentary

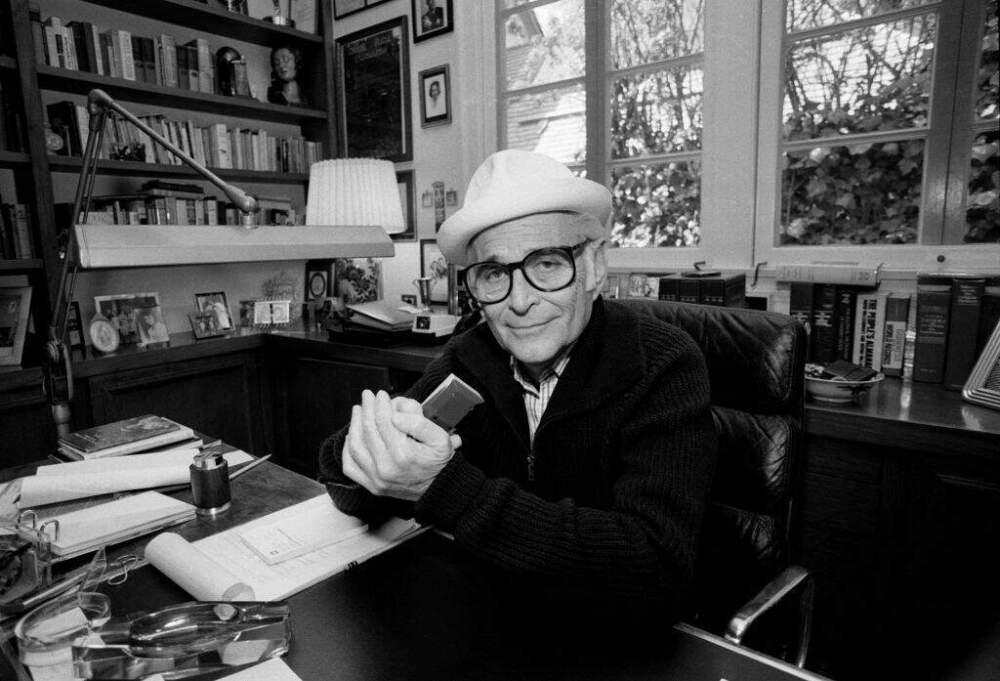

Norman Lear made people talk

By the basic measure of career hits, Norman Lear, who passed away this week at the age of 101, was the Pete Rose of television –– all the hits, without the baggage. As Bob Hope once observed, “We can all be proud of TV and its owner, Norman Lear.” But it’s not the sheer number of his successes that makes Lear’s legacy special. It’s the complexity and nuance of what he created, in a medium that, until he came along, demonstrated precious little of either.

In the wake of Lear’s death, I’ve been reflecting on his work, and specifically his best known and most complicated creation: Archie Bunker. I grew up on “All in the Family,” watching it in reruns with my politically liberal family in the 1980s and returning to it again and again over the years. It’s one of the shows I associate most with growing up, and also with my own evolving awareness of the American political and cultural fabric.

“All in the Family” was deeply shocking television to contemporary viewers when it debuted in 1971. That it’s still widely remembered as the first show to feature the sound of a flushing toilet is a testament to just how Leave-it-to-Beaver-tame television had been up until that point. But simply shaking up audiences wasn’t the point: Norman Lear intended to get Americans talking about real issues. The show took on religion, sexual orientation, gender, and –– in an episode of one of its many spinoff shows, “Maude” –– the first sitcom abortion.

But its most pointed and biting commentary was reserved for race. The Jeffersons, who lived next door (until they ‘moved on up’ with their own wildly popular spinoff show in 1975), were a constant challenge to Archie’s worldview. Meanwhile, for many viewers, the single most savored moment in the series’ nine-year run was when Sammy Davis Jr., appearing as himself, kissed Archie on the cheek –– and the look on Archie’s face that followed.

“All in the Family” was a beautifully crafted show. The writing was as sharp and taut as the national tensions it played with, and Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton formed one of the best comic actor pairings in TV history. At the show’s peak, it reached nearly 60 million viewers.

And this is where things get more complicated: For those who got it, “All in the Family” was a radically subversive commentary, demonstrating the ridiculousness of bigotry by taking it to its (il)logical conclusions.

But while the intended audience may have been American liberals, the fact was, there were a whole lot of others watching as well. In 1972, a whopping 60% of all television sets in the country were tuned in every Saturday night at 8 p.m. to see what Archie Bunker would say next. What did all those Americans hear in Archie’s voice?

Some heard, much to Norman Lear’s chagrin, a charming reflection of their own very real thoughts. This isn’t just anecdotal. In 1974, the social psychologists Neil Vidmar and Milton Rokeach conducted a study with groups of teen and adult viewers. Asked if they saw anything wrong with Archie’s referral to minority groups as “coloreds, coons, Chinks, etc.,” 43% of adults and 35% of teens saw “nothing wrong.” Asked if, in his arguments with his liberal son-in-law Mike, Archie was winning or losing, 40% of adults and 42% of teens saw him as winning.

Nearly 50 years later, that perception of Archie as the rough-at-the-edges-but-ultimately-lovable winner was echoed on the largest of national stages when Steve Bannon admiringly said of his newly elected boss, Donald Trump: “Dude, he’s Archie Bunker.”

But what about the liberals who watched “All in the Family”? I fear Archie didn’t serve us all that well either. In laughing at his buffoonery, many of us found an escape from examining our own innate prejudices. Being in on the joke allowed one access to an exclusive and smug club of elites who couldn’t possibly be racist.

Over the years, there have been many satirical heirs to Norman Lear’s invention. One of those, comedian Sarah Silverman, whose early act was essentially Archie Bunker in Jewish drag, decided to leave the approach behind after coming to the realization that she was toying with racial dynamics in ways she hadn’t fully thought through, and that might be doing more social harm than good. (Somewhat cornily, I called her podcast one morning two years ago to tell her how much I admired her willingness to do this kind of self-work in public, and we had a rather poignant moment.)

So, what’s the final verdict on “All in the Family”? Do we hold it up as a bit of groundbreaking and complex art in a medium which, up until Norman Lear, had always played it safe? Do we toss it into the dustbin of history as a valiant but ultimately failed experiment in social awareness raising?

Norman Lear wrestled with these questions himself, right up until the end of his life. In 2009, he told The Los Angeles Times, “I can’t honestly say I can see anywhere where we changed anything… But what I have are thousands of memories of people relating to me that we made them talk. And you know, the funny thing is, people are still talking.”

In a country where honest and uncomfortable conversations around race are still so hard to find, I’ll take that. Thank you, Norman Lear, for a remarkable life and for leaving us with art still worth talking about.