Advertisement

Commentary

'When the dragon eats the sun': Why I'll chase the eclipse

In 2017, my family and I saw the Great American Eclipse, as the media dubbed it, from a spot close to the centerline in Grand Teton National Park. Though we were positioned for totality, when the moon completely covers the sun — the only time we could watch with the naked eye — the spectacle lasted less than 2 1/2 minutes.

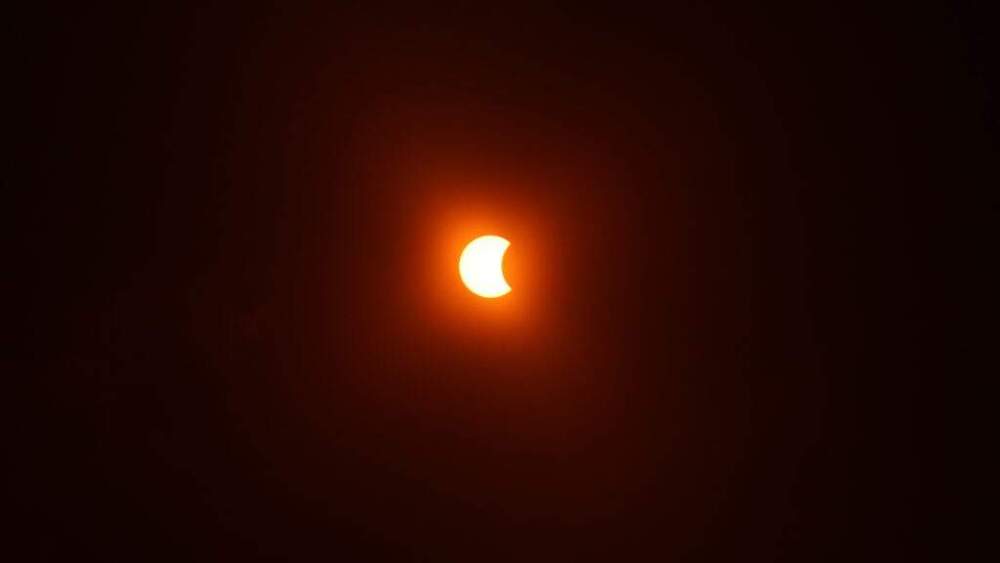

It wasn’t enough. But this year we have another chance, because April 8 the moon’s shadow, only about 115 miles wide, will race 1500 mph from south of Baja California through Texas and on to New England and Newfoundland, enticing millions of us to gaze upward at something greater and more wondrous than ourselves.

I am an eclipse chaser and now I am packing my telescope, emblazoned with an Ancestral Pueblo sun spiral, and preparing to fly to Mexico where the prospects of clear weather are best. This will be my third total solar eclipse, one with a promise of nearly 4 1/2 minutes of totality.

This year, my older daughter is away at college while the younger one, at last a teen, shouldn’t be absent from school, necessitating my wife to also stay home. What was a family vacation last time will be a solo trip now, raising anticipatory emotions I haven’t yet grasped: excitement from the travel; loneliness from the separation; and, without family to hold close, melancholy about the end of the world, when a dragon eats the sun.

For ages, eclipses have been harbingers of doom. How else to understand goosebumps from the sudden chill before totality, that unearthly gray light, the disappearance of birds? How else to interpret those shadow bands, spectral threads evanescent as smoke and rippling across every surface; sizzling in the imagination, as from a crack to the underworld, but in reality silent. When the sun finally bursts out of that hole in the indigo sky and overwhelms its own corona, what relief, what ecstasy, must we feel at the return of the light.

After the Grand Tetons, we flew to Los Angeles to see my father, who was earlier diagnosed with liver cancer. He was comfortable, and eating and doing as well as expected for someone 92 years old. When I was a boy, he showed me how to find Polaris by following the Big Dipper’s pointer stars. That was the time of the Mercury project, and our astronauts were taking their first steps off the Earth. Later, he gave me a small telescope and then bought the "Larousse Encyclopedia of Astronomy," a thick, authoritative book published in the early years of the space age.

I spent many afternoons leafing through Larousse, which was filled with hand-drawn illustrations and a few tinted paintings of the planets, now quaint but based on the best knowledge of the time. Earth-bound telescopes — all we had back then — showed Uranius as a ball with fuzzy cloud bands, Neptune as a featureless disk and Pluto, merely a pinpoint among the stars.

When I told my father about the eclipse, he said he was unaware of it, having stopped following current events. Instead, he was content to sit in the shade of his porch and watch the cars driving by. My mother, who was in the early stages of dementia (though we didn’t know it), was glad we were visiting, since we didn’t come back very often from the East Coast.

A few weeks later, however, I returned for my father’s memorial service. As we sorted through his possessions, I searched for that old copy of the “Larousse Encyclopedia of Astronomy,” but it was lost long ago.

During the long flights for this year's eclipse, I’ll probably reminisce about preschool, when my daughters lay on dog blankets and gazed at the moon through the dining room skylight. I’ll think about that August night, on the outskirts of town, when my family and I watched Perseid meteors streaking overhead; or the time I set up my telescope to show them the brilliant crescent of Venus.

I’ll remember my mother, who survived a bout with COVID but passed away a few years ago, peacefully, in her bed at an assisted living facility. We had saved my father’s ashes for this eventuality and then gathered, brothers and sisters with our growing families, to say goodbye to our parents, their essences scattered together at sea.

Lately this refrain from “Fiddler on the Roof” has been playing in my mind:

Sunrise, sunset,

Sunrise, sunset,

Swiftly fly the years,

One season following another,

Laden with happiness and tears.

It expresses the cycles of time much as the sun spiral does on my telescope. Drawn from a petroglyph, the spiral track is both the star that gives us life and its path across the heavens.

Yet this rhythm in song and sky is more than my children growing up, my wife and me growing older, my parents gone. It enmeshes us in the daily circuits of the sun, the monthly phases of the moon and the annual wheeling of the constellations. Along with the grander, more complex pattern of eclipses, we hear an astronomical refrain reminding us that we are of the universe, not separate from it.