Advertisement

Commentary

Why fairy tales are still essential

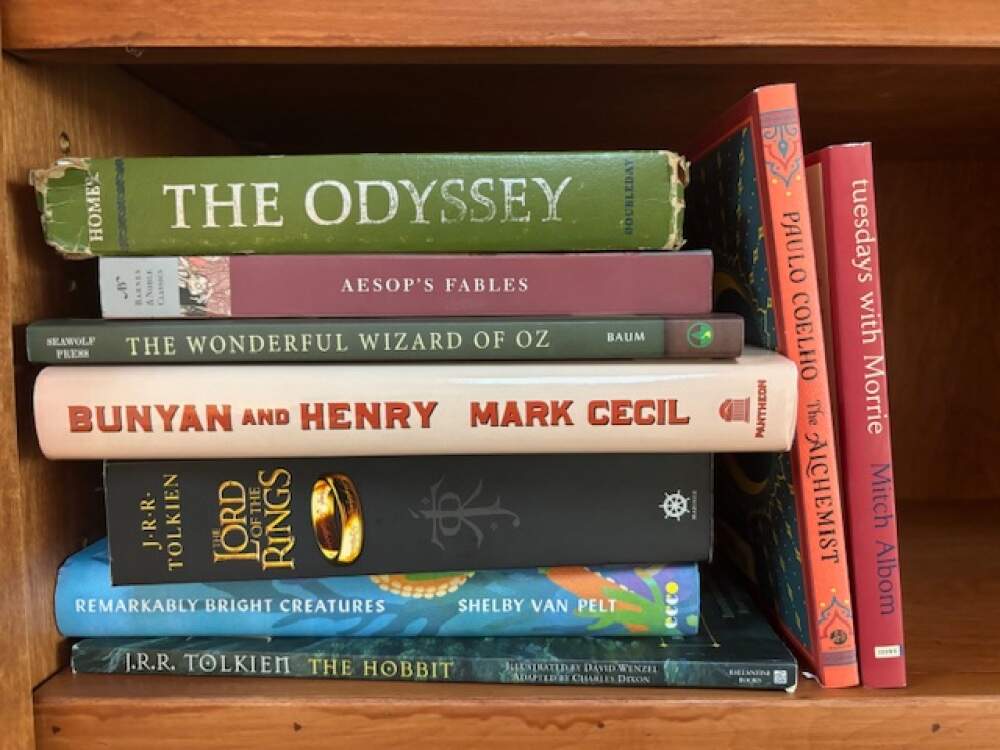

I was an edgy teenager, somewhere between grunge and jock. In the late 90s, I had bleached blonde Eminem hair. I listened to the Beastie Boys and Bob Dylan. I was also a sports fanatic who played basketball and ran track in high school. I wasn’t gonna be boxed in. As a freshman in college, I was pretty puffed up about my reading tastes, too. I read Beckett and Faulkner and Herman Hesse. I drank in the Beats and the post-modernists. I was trendy, intellectual, counter culture. I knew what was what. But then something unexpected happened. Something, frankly, a little bit embarrassing. I picked up Paulo Coelho’s “The Alchemist” and began to get that feeling Emily Dickinson describes as that of true poetry: “as if the top of my head were taken off.”

In its review at the time, Kirkus called “The Alchemist” “a bag of wind,” and a “placebo,” whose “characterization and overall blandness suggest authorship by a committee of self-improvement pundits.” Beckett and Hesse this was not. I wished William S. Burroughs’ “Naked Lunch” and Ezra Pound’s “Cantos” had hit me like Coelho did. But they didn’t. “The Alchemist’s” on-the-nose message, simplistic fable qualities and hopeful, spiritual ending made me think, this is what great books can do.

For the sake of maintaining my teenaged self-styled literary image, I kept my love of “The Alchemist” to myself, and I’ve largely kept it on the down-low since.

Thirty years later, “The Alchemist” is one of the best selling books of all time, it’s still on the front table at books stores, and it remains as unfashionable as ever to say you love it. In today’s award-winning books, prestige television and cinema, critically acclaimed storytelling still tends to favor grim settings, morally ambiguous antiheroes and challenging stylistic innovation.

Yet I remain a sucker for “The Alchemist.” In time, I’ve come to accept myself as someone who craves a fairy tale, even as an adult. What I didn’t know as a teenager, but what I do know now, is that I’m not the only one.

In time, I’ve come to accept myself as someone who craves a fairy tale, even as an adult.

The father of modern fantasy, J.R.R. Tolkien, believed that escapism, hope, and happy endings were powerful psychological needs. In 1947, the author of “The Hobbit” and “The Lord Of The Rings” published a lecture, “On Fairy Stories,” in which he discusses at length how the fairy tale is definitely not just for children. Imagination and fantasizing are natural human activities in children and adults alike, he explains, and he then goes on to define a few rules of the genre.

One rule is that fairy tales mean it. As Tolkien writes, “if there is any satire present in the tale, one thing must not be made fun of, the magic itself.” “The Alchemist” — whatever you want to say about its prose — absolutely believes what it is saying. That’s part of its power for me. You can just sense that the author is overflowing with an urgent, essential truth about the nature of human fulfillment, and he wants the reader to take heart from it.

Tolkien goes on to praise how fairy stories offer consolation and wish fulfillment. Humans delight in imagining they have the ability to speak to animals, escape industrialization, possess magical powers and ultimately avoid death. Tolkien says the hope offered by fairy tales isn’t a kind of flight from reality by a coward, but rather, the daring and clever prison break from the human condition.

As for the happy ending, Tolkien coined a term in the essay, the “eucatastrophe.” (His neologism adds the prefix “eu” onto the word catastrophe, rendering its literal meaning “good catastrophe.”) When the happy ending arrives, “we get a piercing glimpse of joy, and heart’s desire.”

One contemporary teller of adult fairy tales is Mitch Albom, author of “Tuesdays with Morrie” and “The Five People You Meet In Heaven.” I interviewed Albom a few years ago and asked him about Tolkien and the adult fairy tale. “We’ve become more attracted to stories of bad people, broken people and irredeemable people,” Albom told me. “We are perfectly fine with stories that end with everyone dead and there’s no moral to it. Happy endings, for the most part, are considered not real, not serious, not literary.”

Albom, who like Coelho is widely read but often critically dismissed, talked to me about such popular, darkly-themed shows as “Succession,” “The Sopranos” and “Billions.” Albom says he enjoys those shows, but nevertheless, “I, for whatever reason, choose to tell stories of hope. I work in Haiti and live in Detroit; I don’t need any more ‘serious.’” (Tolkien had served in World War I. He, too, had seen his share of serious.)

I wanted the same thing for my grown-up readers as I wanted for my own children: escape, reassurance, delight.

Another recent entry in this category of adult fairy tale is Shelby Van Pelt’s runaway debut bestseller “Remarkably Bright Creatures.” Van Pelt tells the story of a friendship between a widower and a gentlemanly, philosophizing octopus named Marcellus. While the book is pitched as a literary mystery, it has the hallmarks of the classic Tolkien fairy tale: an unquestioned magical element (an erudite octopus), and an improbable, upswinging ending that the reader deeply craves.

I asked Van Pelt about the emotions she wanted her audience to feel at the end of her book. She answered, “Hope that I can change. Hope that it’s not too late for me to do this thing I want to do, or start on a new path.”

What struck me about Van Pelt’s answer is how similar it is to the feelings I’d like to create with my own debut novel, about two folklore heroes in a mythic America. My book, “Bunyan and Henry; Or, The Beautiful Destiny,” literally began as a bedtime story that I made up for my children. As I told the story nightly over the course of a month, there were plenty of dark cliffhangers, bouts of gloom and stretches of desperate suspense. But I always knew that I would arrive at a happy ending. I didn’t want my children to feel perplexed, stressed or down at the end of my story. I wanted them to escape into a world of courage, beauty and love.

Later, I expanded this bedtime tale into a larger work of literary fiction for adults. The final version is a story that explores much of the dark underbelly of the American character — racism, capitalism run amok, class, indigenous conquest and environmental blight. But I kept the happy ending. I wanted the same thing for my grown-up readers as I wanted for my own children: escape, reassurance, delight. The piercing glimpse of joy and the heart’s desire.

“I want to write something that if it’s the last book you read before you die, you would feel it had given you something good to leave on,” Albom told me.

While many adults may find the idea of reading a literary fairy tale as frivolous, I see it differently. To have hope, to crave hope, and to give hope, are some of the best parts of being human. I can’t think of anything more serious for art to endeavor.