Advertisement

Commentary

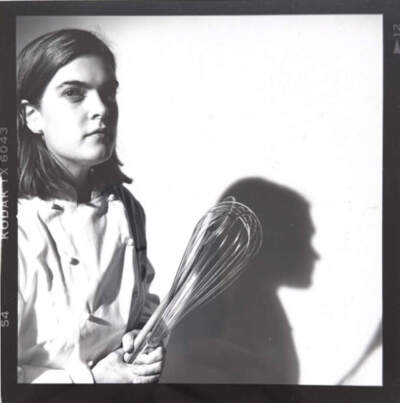

Ana Sortun: Food that makes sense in my heart

Resume

Editor's note: Ana Sortun is an award-winning chef, author and restauranteur. Considered one of the country’s most “creative fusion practitioners,” she opened her first restaurant, Oleana, in January 2001.

Sortun got her start in restaurants early, in Seattle, her hometown. By 14, she had a job washing dishes in a Mexican restaurant (Pueblo Indian style, she tells me) — but she was most intrigued by what was happening in the kitchen. The owners of that place, a couple from Albuquerque, New Mexico, indulged her interest; they paid for Sortun to attend cooking classes. By 16, she was running their Sunday brunch. By 19, she was studying at a cooking school in Paris.

Sortun didn’t grow up eating the Middle Eastern flavors she’s known for today. An encounter with a customer at Casablanca (a long-time Harvard Square restaurant), led to a trip to Turkey for the first time — and that experience inspired a love for the region, and a desire to expand people's understanding of Mediterranean food.

She feels at home in her kitchen, in her restaurants and at Siena Farms, the organic farm in Sudbury, Mass., that’s owned by her husband Chris Kurth, and named for their daughter. “To me, home is about being deeply connected to a sense of place. So, being really connected to land, through food, makes sense in my heart,” she says.

Cog talked with Sortun in advance of her appearance at “This is what makes Boston home,” an event at WBUR’s CitySpace on May 30. This piece, which has been edited for length and clarity, was excerpted from an interview. — Cloe Axelson

I went to a very small cooking school in Paris when I was 19, where I studied classical, strict French cuisine. But in order to do that, I had to be fluent in French. So instead of going to college, I went to a little tiny French school for two and a half years and studied the language until I could pass a fluency test. The cooking school was an intense experience — like 15-hour days, because we were studying and working — but it was a great experience.

People ask me: What did you learn in France that you couldn't learn in the United States? For me, it was really this connection to the quality of the ingredients. When you go to the markets, if something doesn't look good, you don't buy it — and you don't use it. Just because a recipe calls for strawberries, doesn't mean you use them.

If the strawberries don’t look good, you learn how to improvise using the stellar ingredients that are available. That really was, I think, the foundation to a lot of things for me.

I love Italian food. I love French food. I love all food! In the central Mediterranean — in the south of France or Spain or Italy — the food is heavier, more focused on meat, less focused on vegetables. But in places like Turkey and Greece, there are entire meals made out of small plates — and mostly vegetable dishes — which I think is an incredible way of eating.

When I went to Turkey for the first time, I tasted food that was so rich with flavor — from spices and from ingredients like olive oil and pomegranate molasses. There were so many vegetables, which was for me, a complete revelation. I had no idea it was even possible to make vegetables taste like that when I first tried them.

On one of those early trips, my host and mentor, a woman named Ayfer, asked 35 of her friends to make a dish that they loved for lunch, something that they thought represented that region of Turkey.

At the time, I didn’t know any of the ingredients or the flavors, but I was so excited to be tasting all this food, I could barely sit down — I just kept taking notes. Eventually I realized that even though I’d tasted 35 dishes — all delicious, all incredibly rich in flavor – I still felt really good. I couldn’t believe it. There’s no way you could taste 35 individual French dishes and not be in a coma.

I thought the Middle Eastern approach was a really interesting way of cooking and thinking about food. It’s really easy to make something taste good, if you add a lot of sugar or fat to it. But if you are actually highlighting true flavor from the ingredient, you don't want a lot of sugar or fat.

When we opened Oleana almost 24 years ago, my mission was to expand people's perception of Mediterranean food. I wanted to bring Middle Eastern flavors into the mainstream by marrying them with New England ingredients.

Cooking seasonally for me means getting the best ingredients available at the time, and learning about the nuances of a season. Capturing something in the moment — at its prime — really does make a difference in flavor.

Garlic, for example, comes up in spring as green garlic. Then it shoots off garlic scapes, and then it shoots off garlic flowers and then you have fresh garlic, before it gets cured. The plant goes through these many stages – and all are edible and delicious, but you have to catch them at the right time.

Or a potato. A fresh-dug potato isn’t anything like a potato you might find in a grocery store. Its skin is so thin that it’ll just rub off; and when you cut it, because the concentration of sugar is still so high (instead of starchy), it almost sticks to the knife.

At Siena Farms, like a lot of farms in New England, parsnips are one of the first spring crops; they arrive with nettles and sunchokes, and then chives and radishes.

Once the ground is thawed, farmers do a dig for parsnips and sunchokes. We work so hard to make things sweeter — we add maple syrup, we add brown sugar — but parsnips have this natural sugar in them like no other vegetable, particularly the ones that “overwinter.”

Parsnips are similar to a squash or a sweet potato, but they also have a lot of different dimensions. There’s an earthiness, a funkiness to them, an umami, and an acidity as well.

I love cooking parsnips as though they are meat, and doing long braises on them. I love wrapping them in bacon. When you roast them, they become kind of leathery and chewy. I love parsnips with olive oil; the more extra virgin olive oil, the better — they caramelize maybe two or three times more than any other vegetable. They really are kind of a magic vegetable.

If you were to do a side-by-side comparison of a California fall parsnip and a New England spring-dug parsnip, hands down, New England’s would win. The Northeast Kingdom's parsnips are some of the best in the world.

I love when people feel good after they've eaten. So they've eaten, they've eaten quite a bit and they still feel really good. That to me, is great cooking.

When you set out to cook a special meal, you put your best effort into maximizing flavor. But you’re also highlighting something that you think is important. Whether that’s a recipe or something else. For me, it’s always about highlighting the ingredients – something that’s so incredibly radiant by itself, but requires effort to keep its integrity.

I'm a big ingredient forager. I'll do anything. I just want the real deal. No chemicals, no s— in it. Just give me the real thing. And you have to look really hard for that.

The tomato paste we use at Oleana is imported from the southeast of Turkey. It gets cooked down there, usually over smoke and a wood fire. It’s like a sun-dried tomato puree, but it also has all the dimensions of a tomato — acidic, sour or tart, sweet, and it's a little bit salty from just the concentration. You can't cook Turkish food without good tomato paste.

Spending all this money on tomato paste doesn’t make us money. But it’s the idea, the philosophy. When you have concentrated flavors, everything tastes better.

I think food brings people together; food is a reason to get together. You can lure people to the table, by describing the food and making it sound so delicious that they can’t refuse. And then, of course, if the food is delicious, it enriches the conversation, and the joy of the meal.

When we cook, we want something to taste good, and we also want it to look good. We also might think about texture, giving someone different sensations — creamy or crunchy — so that eating is a little more exciting.

Usually people stop there. But I also love when people feel good after they've eaten. So they've eaten, they've eaten quite a bit and they still feel really good. That to me, is great cooking.

This segment aired on May 13, 2024.