Advertisement

Book Excerpt: A Saga Of 'Fishy' Surgery For Chronic Sinus Trouble

"Crank?" was my first reaction when I saw the review copy of the new book "Scrubbed Out: Reviving the Doctor's Role in Patient Care." It was a slim, self-published volume with a cartoon cover and an M.D. after the author's name. Usually, that means rosy, false promises of health panaceas.

But Dr. Salah Salman, the author, is not a crank at all. On the contrary, he's a distinguished doctor, retired now at 75 after an impressive career in the Lebanese cabinet and in high positions at the prestigious Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. It's just that he's so pained and appalled by what he's seen in the American health care system that he has decided to speak out, exposing the unnecessary surgeries, the hyped research, the passive doctors and a few who are out-and-out venal.

His book amounts to a medical cri de coeur — "This is not how it should be!" — and more than anything, it reminds me of a phenomenon called "samizdat" in the old Soviet Union: Manuscripts written by dissidents because conscience would not allow them to remain silent, even though they knew the Communist regime would never allow them to be officially published. Things would have been different if they'd had e-books and print-on-demand back then.

Dr. Salman's critique of American medicine is wide-ranging, from the millions who lack health insurance to the dangerous failure of doctors to police each other. But one of his central tenets is that medicine should not be seen as a business, and that money corrupts its practice. The following lightly edited excerpt, posted with his permission, focuses on an area of his expertise as an ear, nose and throat specialist: Chronic sinusitis, and a form of surgery to treat it that has exploded despite questionable benefits.

Excerpt from "Scrubbed Out" by Salah D. Salman, M.D.

The sad story of chronic sinusitis and functional endoscopic sinus surgery is worth describing in some detail. When fully told, it illustrates many of the problems that have plagued health care and that this book discusses.

As an ENT surgeon, I have witnessed its unhindered growth and development for years; a new theory about the cause of sinusitis and a new surgical technique to cure it were widely adopted fast, without convincing proofs of their value. Evidence against them was suppressed when it surfaced. The medical and hospital leaderships failed to intervene when they should have to monitor quality of care and to control cost.

The see-no-evil attitude of medical doctors helped the wide spread of a questionable theory and a questionable surgical technique. The absence of user-friendly venues provided no opportunity for caring and dissenting doctors to speak out against a lucrative doubtful practice. The power of marketing and promotion contributed significantly to the problem. The current malpractice system, which scares doctors, continues to fail as a quality controller in health care.

The saga of chronic sinusitis and FES began during the last three decades of the twentieth century.

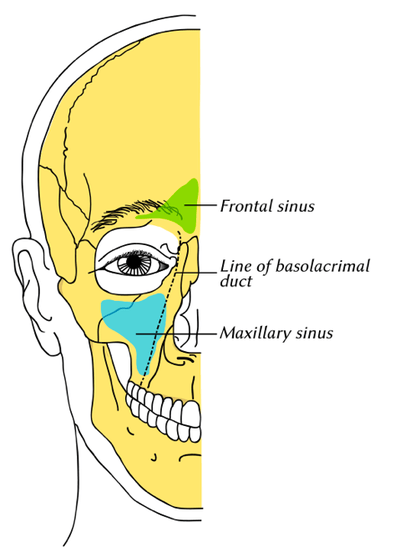

In the 1970s, Dr. Messerklinger, a noted ENT surgeon from Graz, Austria, repopularized an old idea that infections of the paranasal sinuses were due to anatomic obstructions of a key area inside the nose. This area became known as the ostiomeatal complex, or OMC.

The idea was that if the OMC was too narrow or closed, sinus secretions and contents would be blocked before they could follow their normal course of draining to the back of the nose (the nasopharynx) and then being swallowed. This blockage, it was postulated, caused irritation, swelling, subsequent infections, and other signs and symptoms of chronic sinusitis.

At around the same time, the development of surgical telescopes, or endoscopes, made it feasible for surgeons to more safely and easily act on Messerklinger’s theory by surgically widening the OMC. Thus, functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FES) was introduced, and quickly became very popular.

FES and the theory behind it seemed to make a lot of sense, and were therefore widely accepted and adopted in Europe in the eighties, in spite of the fact that neither the theory nor the surgery were actually tested or proven to be consistently effective. Shortly after their acceptance in Europe, Messerklinger’s ideas were also popularized in the U.S., as endoscopes (already in use in Europe) finally became widely available here also.

I should state from the beginning that endoscopic sinus surgery in general, but not the so-called functional one, has certainly helped large numbers of suffering patients, and is considered a major advance in the field of rhinology. Endoscopes allow better and safer surgical access to the nasal cavities and easier surgical removal of obstructing and other pathologies in the nose that cause or facilitate persistent sinus infections. They have also been successfully used in removing intranasal tumors and in cranial- base surgeries, with less morbidity than older techniques that require skin cuts and/or craniotomies.

The criticisms in this chapter are aimed only at the common abuses of functional endoscopic sinus surgery. FES quickly acquired enormous -— and in retrospect, suspect -— popularity in the U.S.

Shortly after its introduction, the reported incidence of sinusitis increased rapidly and for no apparent reason. For example, from 1986 to 1988, the federal government reported fifty million workdays lost to sinusitis. Between 1989 and 1992, the numbers increased to seventy-three million. I suspect that the numbers would not have increased so dramatically had FES not been introduced, aggressively marketed, and popularized.

Indeed, because FES was lucrative, its indications were stretched to a suspect extent. Any facial pressures or pains were wrongly ascribed by certain physicians to sinusitis and were considered surgical indications, even in the absence of expected abnormalities on nasal exams and sinus CT scans. Patients frustrated with their treatment-resistant, chronic facial pains were easily convinced to undergo this new, “miraculous” surgical technique.

FES gained popularity among American surgeons through dozens of two- to three-day teaching courses that were offered each year nationwide. The cost of such courses was around $1,500, and the organizers made money for the institutions hosting the courses. Endoscopes manufacturers lent all the instruments needed during the courses to participants for free. The sales of these costly instruments rapidly soared, as one would expect.

FES was publicized through a large number of complimentary presentations in well-attended, national professional meetings. These meetings unfortunately lacked critical reviews and they greatly exaggerated claims about FES. They facilitated the premature marketing of a lucrative surgical technique before it was adequately tested and proven.

...this technique did not undergo the scrutiny that is normally required for FDA approval of new medications.

In 1986, I, like hundreds of my colleagues, did not foresee the abuses that would follow in the wake of FES’s increasing popularity. We became interested in this new surgery because it seemed logical and promised to cure the frustrating problems of chronic sinusitis by directly addressing its supposed main cause: an obstruction in key areas of the nose. In the late eighties, I took courses in FES, read a great deal of the literature on the subject, and dissected specimens independently. I also spent several days at the Johns Hopkins Hospital to observe Dr. David Kennedy operating, and later following up with his patients in the outpatient clinic. (Dr. Kennedy is rightfully credited with introducing and popularizing FES in the U.S.)

It took me several months to become comfortable with this new technique, after which period I started using it in the operating room. At first, I used it very conservatively, because I knew it could potentially have serious complications. Operating in such close proximity to the eyes and the brain made blindness, intracranial complications, and even death very real possibilities (the risks increased, of course, in unskilled hands). A couple of years later, when I felt I’d acquired sufficient mastery of the technique, several of my colleagues and I, out of conviction, started organizing teaching courses ourselves in Boston. These were always very well attended.

In the nineties, however, many surgeons, including myself, gradually developed opinions about FES that were different from the dominant ones, which were all overwhelmingly positive. First, we noticed that, although we used the technique carefully and became quite practiced in it, our success rates did not compare well with reported and published ones.

For my own part, after I’d enthusiastically performed surgeries for a couple of years, I observed that FES was not always delivering the expected and reported cures. The follow-up data on my cases were not as good as those reported in meetings and the literature. When I compared notes with colleagues, I found out that many shared my skepticism. I became alarmed by the large numbers of sinus surgeries performed nationwide with doubtful or suspect indications, and by the absence of convincing, serious, long-term studies to confirm the value of these surgeries.

We also started observing that certain overconfident surgeons who had not adequately educated or trained themselves were performing this surgery. In effect, they were simply capitalizing on FES’s popularity. As a result, the incidence of serious complications rose quickly. In the nineties, FES was the number one reason that ENT surgeons were taken to court for alleged malpractice.

A system that does not provide a forum for critics to be heard or their opinions acted upon is not a good system to protect patients and control cost; it is a system crying out for reform.

This suppression of critical opinions eventually led many doctors to give up fighting against the abuses of FES. The medical and business beneficiaries of this “miraculous” surgery are too mighty to fight; they have a whole arsenal of political, legal, and monetary weapons with which to resist control and regulation. A system that does not provide a forum for critics to be heard or their opinions acted upon is not a good system to protect patients and control cost; it is a system crying out for reform.

Present Treatments of Chronic Sinusitis

Unfortunately, most of the currently published research has had little impact so far in clarifying the definition and treatment of chronic sinusitis and in halting abusive surgery. To this day, different specialties, as well as doctors within the same specialty, continue to disagree on criteria used to diagnose chronic sinusitis. Many doctors continue to lump different diseases and conditions under the heading of sinusitis, including nasal allergies, nasal septal deviations, large turbinates, migraine headaches, and ill-defined, atypical facial pains. This is a source of confusion to doctors and to the public in general, and results in high treatment costs and the continued suffering and frustration of many misdiagnosed, mismanaged patients.

...most allergist-immunologists and infectious disease specialists continue to manage sinusitis cases without learning how to conduct the absolutely necessary intranasal examination before starting treatment.

In contrast, an infectious disease specialist will probably prescribe one or more antibiotics; if oral antibiotics do not seem to work, costly intravenous antibiotics may be administered for as long as six weeks.

If the patient undergoes a CT scan of the sinuses, radiologists have a tendency to report common, normal intranasal variants as pathologies, worthy therefore of surgical intervention. For example, if this hypothetical patient has a nonsignificant retention cyst in one cheek or maxillary sinus, he will probably receive an unnecessary referral to a surgeon and undergo an operation to excise this usually asymptomatic cyst. This is a common occurrence, and one that flies in the face of research that has long since proved that these normal variants do not cause sinusitis.

Sadly, in addition to those radiologists who are simply unaware of relevant research and common knowledge, a minority of ENT and sinus surgeons contributes to the abuse of sinus surgery, and knowingly recommends and performs surgery even on patients with normal CT scans. To add insult to injury, pathologists continue to report chronic inflammation in normal surgical specimens, as if to provide legal and ethical cover for surgeons who operate on patients with normal sinuses or doubtful sinusitis.

But the story doesn’t end there. If our hypothetical patient is referred to a surgeon for an “abnormal” CT scan, he will receive different surgeries depending on the surgeon’s expertise. If the surgeon is an otolaryngologist, some kind of sinus surgery may be recommended. If the surgeon is an oral surgeon, he may suspect a TMJ disorder and recommend night guards or even a realignment of the teeth. If the referral is to a pain specialist, the patient may end up receiving physical therapy or even Botox injections!

I have not observed a serious attempt by hospitals to remedy these sorts of confusing and wasteful situations. Instead, I have witnessed the widespread frustration of both doctors and patients. Colleagues have called me before referring some of their difficult cases and informed me that they have already operated two or three times on patients without success and do not know what else to do. My answer has remained the same: a diagnosis is necessary first, before planning management.

My experience has proven that many of these patients prove to be sufferers of atypical facial pains, and not of chronic sinusitis; hence, it is no surprise that surgery failed to alleviate their suffering. Atypical facial pains may be due to a variety of causes, singly or combined. The medical profession should invest more time in researching the causes rather than marketing costly new treatments, some of which do not make sense.

I have known many such patients who have received all kinds of treatments and undergone all kinds of surgeries, only to emerge with their pains intact or even worse. Furthermore, the rebound pains after abuse of over-the-counter painkillers and addiction to prescribed analgesics need to be kept in mind as possible causes or contributing factors in these frustrated and frustrating sufferers.

The Business of FES

So far, I’ve outlined how current published research has failed to define chronic sinusitis and to clarify the acceptable indications and timing of sinus surgery. Now, let’s look into why such a situation has been allowed to happen and persist. The unavoidable conclusion is that the business of medicine has been allowed to dominate.

The business of chronic sinusitis and FES in particular, and the business of medicine in general, would not have been possible were it not for the fact that medical leaders have allowed them to proliferate and turned a blind eye to their many failures and other negative consequences. As a result of the free rein, they have provided hospitals, doctors, and related businesses with opportunities for abuses and malpractices.

First, training and credentialing of practicing doctors whose medical school education antedated FES has been woefully neglected, and regulations have been pro forma (Though current residents have ample opportunities to learn the technique during their training.) Second, misleading, confusing, and even false advertising has proliferated. Third, satellite businesses have flourished. Fourth, a minority of doctors continues to abuse their patients and get away with it.

Indeed, the only gestures medical leaders have made toward ensuring safe sinus surgeries have been pro forma.

After this shaky start in training and credentialing, innovative doctors started promoting their own modifications of FES, sometimes before they had been tested or proven beneficial. The business of medicine made this activity possible and acceptable. Meanwhile, fellowships in sinus surgery were created to accommodate young graduates interested in learning more about sinus surgeries and in riding this lucrative wave.

Of course, many such fellowships (and their research activities) were very generously supported by industries involved in sinus surgery. Medical leaders did not intervene, even though conflicts of interest continue to contaminate the teaching, research, and practice of medicine in such fellowships.

As a result of the failure of medical leaders to police sinus surgery, a minority of individual physicians have blatantly abused it.

I have seen a few patients who supposedly underwent one or more surgeries, but who proved later to have untouched sinuses when inspected with endoscopy, studied with CT imaging, and observed at surgery. Some dishonest surgeons have claimed that they operated on the four pairs of sinuses and billed heftily, when they actually hadn’t opened any sinus. There is no easy way to prove their cheating, and no leaders bother to try.

Second, some powerful surgeons operate without adequate justification. For example, a chief ENT surgeon in a Massachusetts hospital with a great public reputation as a sinus surgeon was infamous among colleagues for operating on patients with normal sinuses. He intimidated and silenced residents who dared to ask him embarrassing questions about his surgical indications.

This is a sad corollary of the business of medicine, of a persistent, outdated Hippocratic tradition that requires doctors to defend and protect each other, and of the increasing influence of administrators’ focus on the bottom line.

Equally destructive has been the influence of these powerful doctors on their trainees. A skilled surgeon I know once advised a fellowship trainee to avoid operating on patients with normal sinus CT scans “early in her career,” implying that she could get away with it later on, when she had established a reputation. He added that he could get away with it himself, because he was known as the best sinus surgeon in town. Quite a role model for a training fellow in a prestigious hospital!

As another example of unethical “training,” I once heard from residents about a young doctor who had just finished his ENT training in Boston. He wanted to specialize in sinus surgery; at that point, he didn’t realize what he was in for. Then, he went to Chicago for a one-year sinus surgery fellowship with a famous surgeon in a reputed teaching hospital. After spending a few months with that famous surgeon, he decided to quit because he could neither understand nor tolerate the large numbers of unnecessary surgeries that he was witnessing and performing. Out of a sense of responsibility, he even went to the dean of the medical school there to complain. To my knowledge, the only response administrators made was to grant the young doctor permission to resign without prejudice.

So far, I’ve outlined the ways in which FES has proven to be big business while failing to consistently provide help, and how both individuals and organizations abuse it. But FES can have far more serious consequences: it can actively harm patients’ health. Huge numbers of patients have undergone unnecessary, incomplete, or unsuccessful surgeries and have developed serious and lifelong complications. Tragically, their plight continues to be ignored. The only awareness the public has of this problem is of the minority of cases that are publicized in the media. A very small percentage of patients are angry enough to go through the long, expensive, intimidating, and painful (though possibly lucrative) process of suing. Besides, our legal system does not guarantee that even clearly justified lawsuits will prevail in court.

Individual Activism

When I became aware of the many problems and issues surrounding FES, I tried personally to address them, within my capabilities. My efforts included founding two centers at the hospital where I worked, the Sinus Center and the Atypical Facial Pain Clinic, to conduct studies and to teach.

Our goals were to discuss and debate difficult cases, to better define the currently loose diagnosis of chronic sinusitis, and to determine acceptable indications for sinus surgery.

That Sinus Center got off to a great start; all the participants were enthusiastic. The patients referred to the center were mostly suffering women, who’d been diagnosed and previously treated as if they had “chronic sinusitis.” In most cases, their conditions had not improved after one or more surgeries, and some had actually gotten worse postoperatively.

It did not take long to reach the conclusion that most of these patients were sufferers of chronic facial pressures and headaches, and that these pains were not related to chronic sinusitis. We based this conclusion on our discovery that these patients had had normal endoscopic intranasal examinations and normal sinus CT scans or MRIs; these findings made the diagnosis of sinusitis very unlikely. Chronic facial pressures and headaches are not necessarily always related to chronic sinusitis, and we were able to understand why years of treatment with medications and sinus surgeries had not helped.

Unfortunately, the center lasted only for a couple of years.

Although we made important observations together, the enthusiasm of certain participants in the Sinus Center soon waned when they realized the implications of our observations meant they would have to change their own understanding and management of sinusitis. Moreover, they judged the carefully designed follow-up protocols, meant to provide long-term data on all or a significant number of our patients, to be impractical. I made every effort to sustain the center, but the leaders at MEEI did not see the need to intervene at my request to help keep the center functioning to advance knowledge, improve the quality of care, and help cut costs. The excuse I was given was that it was not the center’s responsibility to influence the behavior of doctors or to police them. I thought otherwise, but could do no more. I subsequently dissolved it. It was, however, kept on paper, for marketing purposes. I continued to get referrals as the director of a center that no longer existed.

My second attempt to help frustrated patients who continued to suffer from pain after undergoing FES was to establish the Atypical Facial Pain Clinic, staffed by representatives of the following disciplines: ENT, neurology, dentistry, oral surgery, pain medicine, behavioral psychology, and physical therapy. Patients referred to us were evaluated by all the participants together over forty-five minute periods, and an appropriate management strategy was developed by all participants.

...appropriate consultations and proper diagnoses have to be made before management is planned and sinus surgery performed.

I considered it a duty to publicize my findings about chronic sinusitis, in order to change widely held, erroneous perceptions. But in trying to do so, I ran up against active suppression, roadblocks, and disinterest -— just as have other researchers who reached similar conclusions and who’ve tried to make their findings known. I reported this study at one of MEEI’s well-attended weekly teaching activities, the Clinico-Pathologic Conference (CPC). Since I considered it scandalous that surgeons at a well-respected hospital were conducting operations to widen nasal passages that were, in fact, unobstructed and normal, I believed and hoped that my findings would stimulate significant discussions and reactions. I was surprised to discover that I was wrong.

The discussion I was hoping to stimulate by shocking the audience never occurred. Colleagues who I knew shared my opinion did not speak out. The only response I got was that “the jury is still out on this issue.” Full stop. I did not think so. This lack of reaction, to my mind, compellingly illustrates the fact that the business of medicine currently takes precedence over the science of medicine, even in reputed teaching institutions. What a shame.

As a counterpoint to this lack of reaction to my research on the domestic front, my findings have been very well received by a much larger national and international audience. I was once invited to participate in an international rhinology meeting in Washington DC. I was given the privilege of picking the subject I wanted. I chose to speak about FES, and titled my presentation, “The Facts and Fancy of Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery.” I openly criticized the epidemic of unnecessary sinus surgeries performed nationally in the United States. I had never experienced as much applause in my academic life after any presentation, and many doctors I did not know stood in line to congratulate me on my “courage” in speaking openly against the widespread abuse of sinus surgeries.

It is interesting to note that, in comparison to this response, the much less strongly worded papers that I had submitted for publication in the U.S. were turned down with little explanation. I can only conclude that I was swimming against the prevalent current, and that it is politically incorrect to publish criticisms of FES.

The Continuing Saga

Sadly, FES abuse has not only continued to the present day, it has also spawned other suspect surgical techniques that capitalize on FES’s popularity. For example, in 2006, the American Journal of Rhinology, the official publication of the American Rhinological Society, published a very premature report about the safety and feasibility of a new surgical technique for endoscopic sinus surgery, called balloon sinuplasty.

...FES has become an out-of-control, lucrative business. Hospitals encourage abuses because of the business unnecessary surgeries bring. Direct advertising and reporting in the lay media have helped increase FES’s popularity. Critical voices are suppressed or ignored. Conflicts of interest have become commonplace. As a result, we now face an epidemic of unnecessary and incomplete sinus surgeries, which have resulted in deaths and serious complications, and which have significantly contributed to the escalating cost of health care.

Karen Weintraub, our guest contributor, interviewed Dr. Salman recently in The Boston Globe.

"Scrubbed Out" is available at AuthorHouse and Amazon.

This program aired on March 2, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.