Advertisement

Morning-After Pill Disappoints, On To Plan C: More Effective Methods

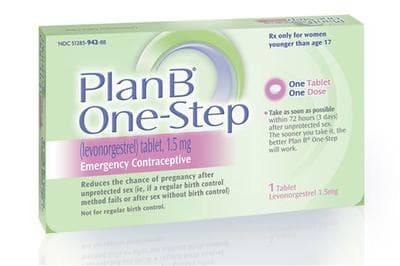

They were splashy headlines this week: The emergency contraceptive pill "Plan B" does not work well in heavier women, and appears not to work at all in women over 176 pounds.

The FDA is considering whether the pills' labels should be changed to warn heavier women not to count on their contraceptive powers, NPR reported; the French maker of a similar pill is already planning such a warning.

But the controversial morning-after pill has a bigger problem than that. Family planning advocates have fought hard to make Plan B easier to get in order to bring down the high American rates of unintended pregnancy. But so far, on that score, it's looking like a dud.

Plan B hasn't made a dent in the stunning statistic that a full one-half of U.S. pregnancies are unintended. This despite its FDA approval way back in 1999 and the growing access to emergency contraception over the last couple of decades — and despite major recent victories for family planning advocates: Plan B is now available over the counter to all ages.

"While there's a lot of data to show it can prevent pregnancy in individual women, we've all been disappointed that on the population level, it just hasn't had the effect we hoped," said Dr. Deborah Nucatola, senior director of medical services at the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. "The unintended pregnancy rate hasn't changed at all."

Why might that be? There are two main theories, Dr. Nucatola said: Maybe the women who most need Plan B aren't using it when they are actually at highest risk for pregnancy. Or maybe they're just not using methods that are effective enough, and women should shift to more effective types of emergency contraceptives.

Enter what we might call Plan C. Around the country, Planned Parenthood affiliates are launching a new campaign called EC4U to educate women and clinical staffs about two more effective methods of morning-after help: Paragard, the copper IUD, and "ella," a relatively new pill that uses the hormone ulipristal acetate, rather than the levonorgestrel in Plan B and a similar pill, Next Choice.

Accumulating data suggest that Plan B has two main weak points. One is weight; it was highlighted in this week's reports, but contraceptive specialists had known for many months that the pill's effectiveness drops in overweight women and approaches nil in women with a Body Mass Index above 35.

"We don't know why," Dr. Nucatola said. "We just know that when you look at women who take it, and stratify it by their BMI, the pregnancy rate goes up" the heavier a woman is.

The other Plan B weakness is timing. The usual window for emergency contraception is thought to be about five days; Plan B's effectiveness appears to drop off quickly after 72 hours. Overall, its effectiveness is estimated at between 74 and 89%, Dr. Nucatola said.

Compare that to the copper IUD, Paragard, at more than 99% effectiveness if inserted within the 5-day window, regardless of weight and timing.

"I think it's surprising to a lot of people," said Dr. Danielle Roncari, medical director of the Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts, which has just launched the EC4U campaign in the state. "It's nearly 100 percent effective and it doesn't change in terms of when you get it placed. So if you had unprotected sex one day ago versus four days ago, it's equally effective. And it has the added benefit of longer-term contraception."

Ella, too, looks good in comparison to Plan B. It retains its effectiveness better for the full five days and in overweight women, though it, too, loses its power when weight gets too high.

"Plan B always will have its place," Dr. Roncari said, "but I think providers are starting to realixe that ella may be a more preferred pill option for women --- and I think that's where we're heading at Planned Parenthood."

The downsides: ella is prescription only, unlike Plan B. And to have an IUD inserted requires both a prescription and a doctor's appointment for an insertion procedure that could run several hundred dollars.

"We know you have to go through a few extra hoops," Dr. Nucatola said. Part of the EC4U campaign, she said, involves helping Planned Parenthood affiliates adjust their scheduling and training to make it likelier that women who want emergency contraception will get a more effective option.

But there may also be advantages to prescriptions and appointments: research suggests that many doctors have not been talking with their sexually active patients about over-the-counter emergency contraception — perhaps they will broach the topic more often if the method needs a doctor's prescription or procedure.

According to the latest data, 11 percent of women who are sexually active have ever used emergency contraception pills, said Megan Kavanaugh, a senior research associate at the Guttmacher Institute, which studies issues of sexual and reproductive health.

That's up from 4 percent in 2002, but still small compared to the unintended pregnancy rate, and it appears the percent of women who are counseled about emergency contraception by a doctor is even smaller — just 3 percent, according to a 2008 study.

Some speculate, Kavanaugh said, that "with the move to over-the-counter, physicians may not see emergency contraception as necessarily within their purview anymore. Obviously, ideally, they’d be talking about all methods, just like they should be talking about condoms even if they’re not prescribing condoms."

Of course, talking about a copper IUD may not help much if it will still cost a patient several hundred dollars she doesn't have to get one inserted. "We're hoping the Affordable Care Act will take care of that for us," Dr. Nucatola said.

Cost is clearly the biggest barrier for patients who want IUDs, she said. "It's easy for us to make sure we have clinicians and supplies and schedules, but how is that patient going to pay for it? The Affordable Care Act basically says women should have access to all birth control methods without cost-sharing."

So IUDs should be fully covered under Obamacare? "That is the hope," she said.

Further reading on emergency contraception:

Here are some basics from the Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts:

The FDA approved Plan B in 1999. It was the first progestin-only medication specifically designed for emergency contraceptive use and was cleared for over-the-counter sales in 2006 for users 17 or older. However, doctors have been prescribing emergency birth control since the 1960s, and studies published as early as 1974 have shown emergency contraception to be safe and effective.

There are now three forms of emergency contraception:

· Paragard, the copper IUC, is the most effective method of emergency contraception. It can be inserted up to 5 days after unprotected sex and can be left in place as a highly effective method of contraception for up to 12 years after insertion. It requires a doctor’s appointment for prescription and insertion.

· Plan B One-Step and Next Choice, progestin emergency contraceptive pills, are available over the counter. Their efficacy decreases with time, especially if taken four or five days after unprotected sex, and they may be less effective for a woman with a higher Body Mass Index (BMI). Plan B One-Step is available over-the-counter without restrictions; Next Choice is available over-the-counter for individuals above age 17 or with a prescription for individuals of any age.

· ella, a ulipristal acetate pill, is available with a prescription and is equally effective up to five days after unprotected sex, including for women with higher BMI.

And a 2011 review paper in the journal Contraception is summed up in this abstract:

BACKGROUND:

Emergency contraception (EC) does not always work. Clinicians should be aware of potential risk factors for EC failure.

STUDY DESIGN:

Data from a meta-analysis of two randomized controlled trials comparing the efficacy of ulipristal acetate (UPA) with levonorgestrel were analyzed to identify factors associated with EC failure.

RESULTS:

The risk of pregnancy was more than threefold greater for obese women compared with women with normal body mass index (odds ratio (OR), 3.60; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.96-6.53; p<.0001), whichever EC was taken. However, for obese women, the risk was greater for those taking levonorgestrel (OR, 4.41; 95% CI, 2.05-9.44, p=.0002) than for UPA users (OR, 2.62; 95% CI, 0.89-7.00; ns). For both ECs, pregnancy risk was related to the cycle day of intercourse. Women who had intercourse the day before estimated day of ovulation had a fourfold increased risk of pregnancy (OR, 4.42; 95% CI, 2.33-8.20; p25 kg/m(2) should be offered an intrauterine device or UPA. All women should be advised to start effective contraception immediately after EC.