Advertisement

Troubled Future For Young Adults On Autism Spectrum

![Michael Moscariello, 32, looks out through the front door of his Cambridge apartment complex. Michael is on the autism spectrum, as is his younger brother, Jonathan. “[My sons are] the pioneer generation” for children on the spectrum, their father, Pete Moscariello, says. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)](https://wordpress.wbur.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/0609_autism01-1000x666.jpg)

“Mom, Dad, what’s wrong with me?”

Michael Moscariello was a smart, thoughtful 10-year-old when that question burst out one evening before dinner.

He knew from kids at his school in Reading that something was not right. His parents knew too; they had a diagnosis. But it was a condition that almost no one had heard of — not doctors or teachers, and certainly not friends or family.

That night, Michael’s parents used a classic diversion tactic. “Nothing’s wrong, nothing's wrong, everything’s fine,” Michael remembers them saying. “Do you want to get pizza?”

“[My sons are] the pioneer generation” for children on the autism spectrum.

Pete Moscariello

May Moscariello, Michael’s mom, had taken him to Franciscan Hospital for Children in Boston three years earlier, in 1988. “They evaluated him and came up with Asperger's syndrome. It was their first case,” May says. She remembers a doctor telling her that Asperger’s was a hot topic in London at the time. The doctors “gave me a lot of written material from England," she says. "None of it mentioned autism."

Today, Asperger's is folded into the broad diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). This includes people like Michael who are bright and articulate, but can’t understand the look that says, I’m serious, or that hint of sarcasm in a friend’s response, or why people back away during a conversation. One in 68 children in America has an autism spectrum disorder.

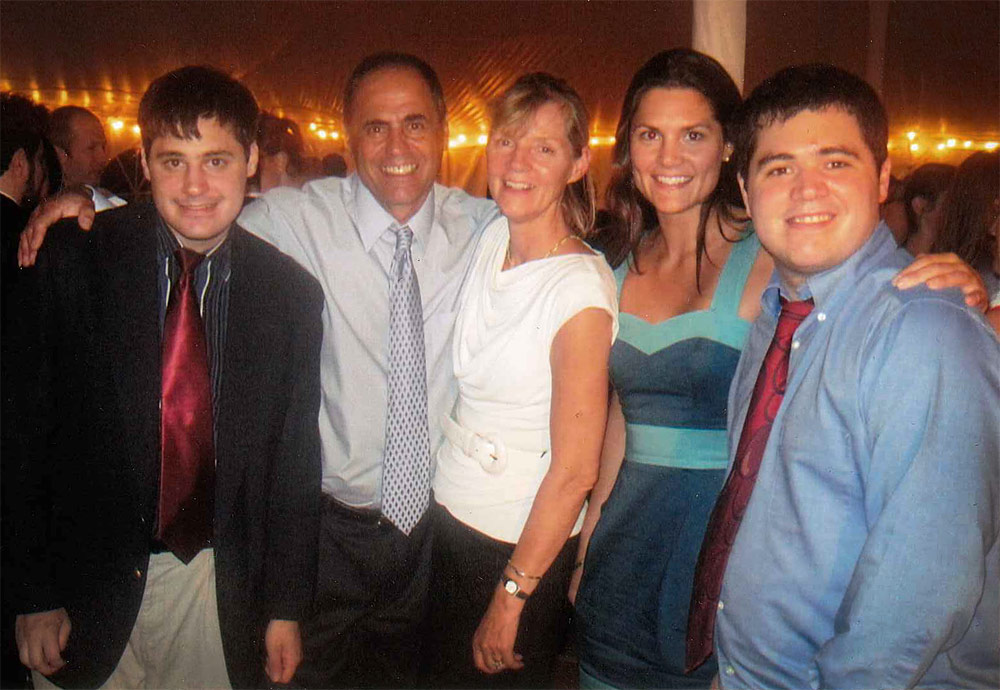

Michael, now 32, is on the spectrum, as is his younger brother, Jonathan, 29, who has a sort of catchall diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. Their lives, as adults with autism, raise troubling questions about whether the flood of children receiving this diagnosis will find meaningful work, safe housing and networks that will help them become happy and productive adults.

Advertisement

"[My sons are] the pioneer generation” for children on the autism spectrum, Pete Moscariello says.

Being The 1st Child With Asperger's — Over And Over Again

The Moscariellos' pioneering journey with autism began with Michael. His childhood was a series of “dead ends, many, many dead ends,” says May, a small, fit woman who coaches amateur figure skaters.

At first, she thought Michael could be happy at the local elementary school. One person on staff had read a little bit about Asperger's. Teachers who weren’t familiar with Michael’s condition still "bent over backwards to try to help,” May says. Through trial and error, teachers figured out how to avoid the emotional outbursts that could ruin Michael's day. He could handle two setbacks, teachers realized, before he would explode.

“I don’t know how they did it, if they had walkie-talkies or what,” May says, but the teachers would know, “OK, one more disappointment and he’s going to blow.” Michael could have stayed in the public elementary school and succeeded academically, May says, but socially, he was miserable.

The Moscariellos went looking for options. It was hard to find a place where Michael’s awkward social skills and emotional outbursts would not make him a target of ridicule, and where the goals went beyond learning to read, which Michael started doing at age 3.

May remembers constant phone calls to doctors, researchers, her insurance plan and other parents. She and Pete drove for hours on weekends to the homes of other families who had young sons with Asperger's, "because all these kids want to feel is that they belong," she says. "[None of the] medical stuff is really going to help them as much as having a friend."

Michael found friends. "We're still searching for that for Jonathan," May says.

May shudders, remembering the times she punished her children for doing things that she realizes now they did not understand were wrong.

One hot day, May asked Michael to pull down the curtains. She meant shades, and “pull down” was not the right phrase to use with a child who takes words at their literal meaning. Michael ripped the curtains right off the wall and was beside himself when May yelled for him to stop.

Michael spent six years at a Lexington special education program for students with learning disabilities. But Michael longed to go to what he calls a “regular high school.” So he went back to Reading, where his dad was head of the math department and the baseball coach. The school built a program for Michael and he persevered.

“I was very proud of myself. I didn’t think I was going to be able to do it,” Michael says. But a friend in Lexington told Michael, “'I believe in you.' Next thing you know, I started straightening up my act, getting more control over my emotions." Michael says Dave, the friend, “saved my life.”

Michael graduated from Reading High School at age 22. A federal law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, requires that schools provide appropriate programs for students, including those on the autism spectrum, until they are 22. Some students stay in high school until they "age out" because they need extra time to complete graduation requirements. Others delay graduation because once they leave school, their access to special education programs ends.

"There is no entitlement to adult services," says Susan Parish, a professor of disability policy at Brandeis University.

One recent study found that more than half of young adults with ASD had not moved on to higher education or had a job, two years after they graduated from high school.

"We knew from talking to parents that outcomes are not great for lots of kids on the autism spectrum when the leave high school," says Paul Shattuck, the study's lead author and an associate professor at Drexel University's Autism Institute. "We were kind of shocked at just how not great things were."

Michael had a mentor, training in social skills and a daily routine that all ended when he turned 22. He and his parents began the next leg of their pioneering journey, searching for ways to help Michael become a happy, productive adult with Asperger’s.

For Michael, The Perils Of Life On His Own

The Moscariellos spent about $40,000 each year for the next five years after high school, sending Michael to residential programs where he learned how to grocery shop, cook, manage a bank account, apply for jobs and live outside his parents' protective home. There are no low-interest college-type loans or tax-free savings plans that cover these programs for young adults with disabilities. That may change if bills pending on Beacon Hill or Congress pass.

The legislation in Massachusetts would also lift an outdated restriction on disability benefits. Right now, no one with an IQ above 70 qualifies; both Michael and Jonathan score well above 70.

But they need help, a lot of help, with their social skills. Michael worries a lot about losing friends. He doesn't want to repeat mistakes he made as a young adult.

“There was a girl I was friends with,” Michael begins. “Every time I saw her, I’d just have to go over and talk to her. I’d be like, 'Hey, it’s me, let’s talk.' " Michael realized he was “talking her ear off” and perhaps missing some clues about whether the young woman enjoyed the conversations. He was devastated the day that young woman said, “Stay away from me, I don’t ever want to speak to you again.” Another friend helped Michael understand what he’d done wrong.

“Sometimes just saying hello is more proper than stopping to talk to everyone I know and see all the time. People got stuff to do. That’s how things work," Michael says. "I didn’t know any of that. Finding out hurt, but I took it as a learning experience."

Michael’s parents call him a worker bee. When he has a setback, he tries again with a different approach. Michael must learn the rules for executing everything from a casual hello to close relationships, practicing steps that many of us take for granted.

Michael’s parents speak to him almost every day and see him once a week.

After five years in residential programs, Michael told his parents he wanted to get an apartment on his own. May and Pete worried that someone might take advantage of their son.

“Michael’s loving and giving and trusting of everybody, that’s the danger,” May says. “He’ll say to me, ‘I’m good mom, I’m safe, I’m fine,' and I would say, 'Yeah, until you’re dead. So wake up.' ”

That conversation happened after Michael told his parents that he’d been bringing people he didn't know very well back to his apartment, people who needed a place to stay. No more, his parents said, or you’ll give up the apartment and move back home.

Michael’s apartment is partially subsidized by the city of Cambridge and the state. He gets Social Security assistance, based on his disability, which covers most of his expenses. He's on food stamps and Medicaid. His parents help with about $300 a month.

Michael is working on a book about his experience with Asperger's. (Read some of his writing.) He also writes science fiction. "Star Trek" and various superheroes have pulled him through many difficult moments. When he was the only kid who didn’t get picked for kickball, he’d wander into the woods and imagine himself saving people. Today, he and his brother both love dressing up as superheroes and going to conventions where they can socialize with like-minded superhero devotees, and feel as fearless as their characters.

'I Want Actual Job Satisfaction'

Michael has not been able to find or hold a job that he says is worth his time. He’s had internships in bookstores, volunteered in animal shelters, and worked at Toys "R" Us, Walgreen’s, a Web hosting company and a grocery store bagging items.

“I had to stand at the edge [of the counter] and wear this stupid apron and say 'Paper or plastic?' so many times that the words lost all meaning,” Michael remembers. He wasn’t allowed to talk to people, something he loves to do, “because if I tried, it was like, ‘You’re holding up the line.’ ”

For two years Michael saw a job counselor at a state agency for disabled adults, but he says everything they suggested was menial work.

“I don’t want to sort through huge piles of batteries,” Michael says. “I want actual job satisfaction.”

He meets once a month now with a jobs counselor at a different agency. In the meantime he plays video and board games a few nights a week with friends, and he writes.

“Mike’s a success story,” Pete, his father, says, “but it’s been a tough road and it’s always going to be.” His parents, who are in their early 60s, remind Michael that they won’t always be around.

“I feel like the window is kind of closing here in terms of getting him everything he needs to be able to live a happy life,” Pete says, pausing to let a wave of emotion pass.

Pete is optimistic that Michael will eventually find the right job. But who will keep an eye on his son? The Moscariellos have a daughter, but Pete says he’s determined to let her have her own life, and not expect her to take care of elderly parents and two brothers with autism.

“As we look for lifelong support for Michael, we don’t know where to turn,” Pete says. “That’s the scariest part, the day-to-day worry I know my wife and I suffer through.”

Worry Increases With Jonathan

At age 3, when Michael's younger brother, Jonathan, started to read, May cried.

“That was my cue. I knew I was in trouble,” May says.

There were other signs of autism: Jonathan was obsessive, anxious and prone to temper tantrums. He would be another exceptionally bright boy, May imagined, struggling against a world he could not navigate and that would not understand him.

The brothers are different. Jonathan is three times more anxious than Michael, May says. Jonathan went to several different schools before graduating from Reading, at the age of 21. But he was too afraid to try the residential programs that helped Michael learn to live independently.

“We couldn’t make it happen without,” Pete pauses, “throwing him off the deep end, you could say, and letting him swim.”

While Michael was still in school, the Moscariellos brought one person after another into their home, trying to find someone who could draw Jonathan out of himself and the house. Finally, a mentoring agency sent Brian Gordon.

“He saved my son’s life,” May says of Gordon. He worked with Jonathan three times a week. Jonathan started playing the guitar, they would go out to eat, and Jonathan got a job.

Then Jonathan turned 22 and, like Michael, he aged out of state services.

“Jonathan was left in a world without Brian, and the world fell apart. There was no one there to support him," May says.

Jonathan had a disagreement with a customer at his job. He lost his temper and was fired. Now, May says, he’s too afraid to work again. The family hired Gordon on their own, with more limited hours. Jonathan, seeing Brian outside the mentoring agency, decided that Brian should become his friend. Jonathan didn’t want to work on any of the life skills Brian thought he needed to tackle. Brian pushed back with new rules for their visits. These days, the two see each other weekly. It's one of the few times Jonathan leaves his parents' house.

The transition from high school into the adult world "is often catastrophic" for young people and their families, says Parish, the Brandeis professor of disability policy. "With the prevalence of autism, we're talking about thousands and thousands of individuals across the U.S. who, when they leave high school, face a dead end."

Parish says it's such a waste. "Denying these individuals their chance to participate in society, civic life, communities, is just a terrible thing to contemplate."

But creating the right opportunities will be costly --- for parents or for taxpayers.

Pete and May have looked at expensive day and residential programs for Jonathan, but so far he refuses to consider them.

“Jon’s very articulate, very bright and he writes well,” Pete says. “He’s got a sense of humor. But his anxieties and fears have just hamstrung him to the point that we’re not progressing right now. That’s our day-to-day worry.”

May, who says she's the stricter of the two parents, tells Jon, “We [your dad and I] only have 20 years left. You’ve got to get your [act] together. We’re on borrowed time.”

May does not blame Jonathan. “The end of the story is that my kids were crushed socially, by the world,” May says.

Pete says the next generation of kids on the autism spectrum — many of whom have more significant challenges than Michael and Jonathan — will be better off than his sons because the services begin earlier and begin to fit the specific needs of children with autism.

But Michael and Jonathan need help now.

"They're tired of being pioneers," Pete says. "They need support."

The radio version of this story aired in two parts. Listen to both below.