Advertisement

How Childhood Neglect Harms The Brain

ResumeLike any new mother, the woman we’ll call Braille was full of hope and excitement the day she welcomed her son into her life seven years ago. “Peter” was 7 years old at the time of his adoption. He'd been living in foster care after being taken from his biological mother.

According to Braille, Peter and his siblings endured years of neglect and abuse living with their biological mother and her violent boyfriend. “It was physical, emotional and continual,” she says.

Peter, now 14, and his adoptive parents are very close now, but the years since the adoption have been challenging. His father recalls Peter's unpredictable anger, and the times Peter would punch him, out of the blue. His mother says her son could be very sweet and affectionate one minute, but then “he would just fall apart and start banging his head against the wall or start screaming.”

Experts have long known that neglect and abuse in early life increase the risk of psychological problems, such as depression and anxiety, but now neuroscientists are explaining why. They're showing how early maltreatment wreaks havoc on the developing brain.

Study Of Orphans Finds Smaller Brains

Dr. Charles Nelson, a Boston Children’s Hospital neuroscientist, studies how children’s early experiences shape the developing brain. Abuse and neglect, he says, can cause significant damage to the circuitry of the brain.

“Let’s say there are 1,000 neurons supposed to wire in a certain way, maybe only half wire that way and the other half wire in an incorrect way," Nelson explains. "By altering the wiring diagram, you are altering behavior and altering psychological states.”

But what prevents the brain from wiring the right way, and how do early experiences get biologically embedded in the brain?

Experts say that chronic neglect and abuse represent a profound threat to a child’s early years, when they are totally dependent on caregivers for food, comfort and other basic needs. The lack of critical care sets off a biological stress response and a flood of hormones, which can damage key areas of the brain.

Many animal studies have documented the deleterious effects of early childhood neglect (by putting young mice in isolation, for example) but in 2000, Nelson had the opportunity to study a population of children: Romanian orphans raised in harrowing conditions in state orphanages.

This gave Nelson a unique opportunity to study the effects of profound deprivation on brain development. Using neuroimaging tools, he compared the brains of the children brought up in the orphanages to those of children raised outside.

“When the kids were 8 to 10 years old, we did magnetic resonance imaging on them, where we can actually look at detailed anatomy of the brains,” Nelson says. “We found that the kids in the institutional group had much smaller brains. We are not sure why they are small, but it is probably due to loss of connections and loss of cells.”

The smaller brains translated into potential problems with attention deficit disorder, anxiety disorders and attachment issues.

While the study's children suffered from extreme neglect in the Romanian orphanages, Nelson believes there are lessons for American children.

“Kids who grow up in families where they are maltreated and then placed in bad foster care look just like our kids in Romania," he says. "When people say, 'Who cares about kids in Romania?' It’s because it is a model system for what happens in the United States every day.”

Lacking The Skill To Behave

At Massachusetts General Hospital, Dr. Stuart Ablon directs Think:Kids, a program for children with behavioral challenges. He says while working with these children, it’s important to understand that they have brains that are not fully developed. They don’t lack the will to behave, he says, but the skill.

“This thinking runs completely counter to the more common philosophy that kids do well if they want to,” he says. “Most people believe if a kid isn’t doing well, it’s because he or she doesn’t want to. We have known forever that is not the case. Now we have the science to back it up.”

Ablon says children with behavioral challenges are not stubborn or unmotivated; just like kids with learning disabilities, children with behavioral challenges lack skills because of differences in their brain development. They don't lack reading and math and writing skills; instead, they lack problem solving skills such as frustration tolerance and emotion regulation.

Trying to motivate them with rewards and punishments is not effective, Ablon says, and punishments like restraints are likely to backfire and ratchet up the aggression.

That was true for Peter, the 14-year-old we met earlier. He is now getting help at Think:Kids and is doing well, but he says the approach he experienced in previous therapeutic settings often hurt more than it helped, like a time at school when he felt a meltdown coming on.

“Several teachers were rushing at me so I reflexively ran out of the room,” he says. “They pinned me down in the hallway. I was being crushed. Being attacked and forcibly shoved to the floor can be extremely painful. I don’t understand how anyone could consider that in any way calming.”

Interaction To 'Facilitate Brain Change'

Ablon and other experts say science is beginning to show that restorative brain change can happen with appropriate intervention and care. Ablon believes change happens when children are helped to repeatedly practice the skills they lack in trusting relationships.

Take for example a child who gets extremely upset and agitated when he is asked to turn off a video game and start doing his homework. Ablon says if the child begins to escalate emotionally, it’s up to the adult to stay calm and try to empathize with the child, to understand the child’s concerns in that moment. “The child will actually calm down and then be open to hearing the adult perspective and being invited to problem solve with the adult,” he says. “It’s that kind of interaction again and again that is the dosing needed to facilitate brain change.”

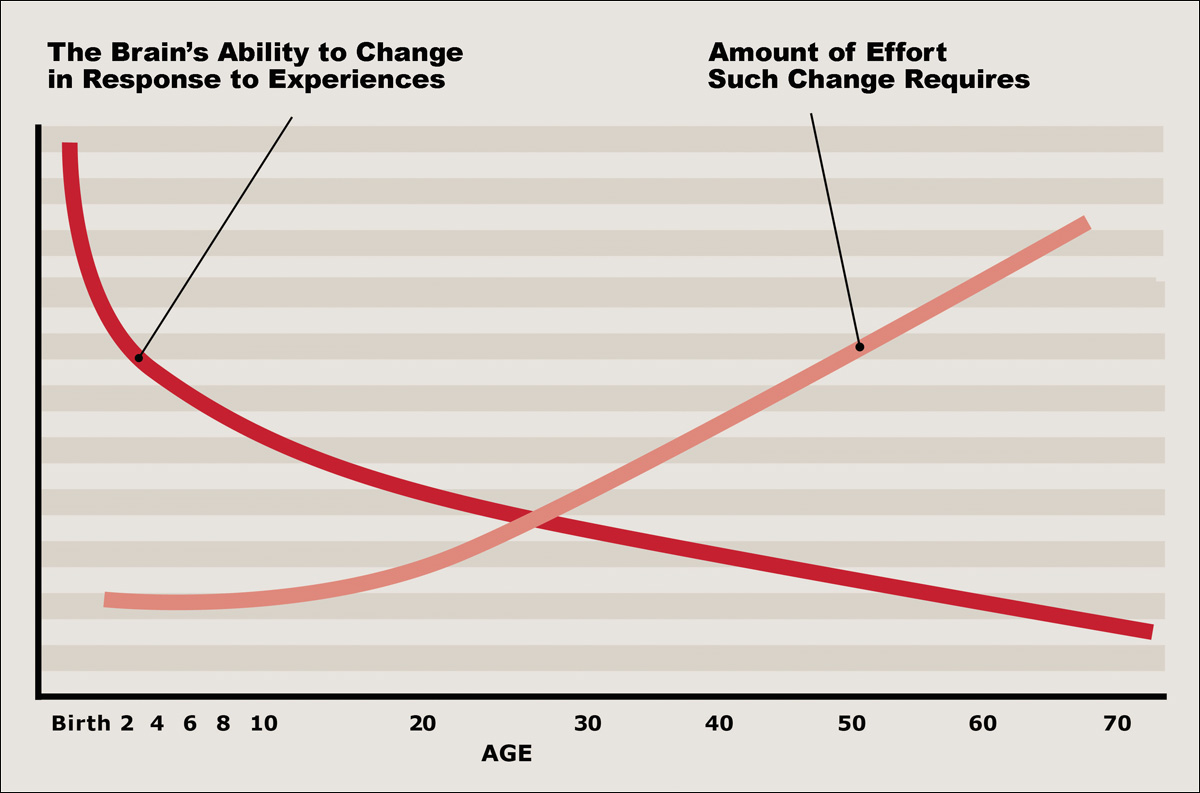

But brain change gets harder as time passes, says Nelson of Children’s Hospital. It’s critical to intervene early before brain damage takes place, he says, to provide support for parents and caregivers, treatment and family therapy and, if need be, to remove children from abusive homes. Interventions done later in life will likely be less successful in rerouting the brain wiring than interventions done earlier, when the brain is more plastic, he says.

“If you have a plastic circuit then you might be able to overcome early adversity when placed in a better environment because the brain is still plastic enough to change," he says.

The cost of delaying is huge — not only in human terms, but also financially. According to a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study, "the total lifetime cost of child maltreatment is $124 billion each year."

Dr. Jack Shonkoff, head of Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, says we must respond urgently to the scourge of childhood neglect, as we have to other public health threats.

In the past, he says, we might have dismissed childhood neglect, not understanding the significant biological damage it caused. That can no longer be the case, he says.

“The science makes it more difficult to walk away," Shonkoff says. "Once you know the science now you have a moral responsibility to say, 'We can’t allow this to go by.' That’s what the scientific understanding has done.”

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this report contained an image of two child brains that WBUR took from a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. WBUR subsequently learned that the image is controversial in the scientific community. We have removed the image.