Advertisement

The Science Of Suicide: Researchers Work To Determine Who's Most At Risk

Resume

Part of an occasional series we’re calling "Suicide: A Crisis In The Shadows"

BOSTON — Up on the 12th floor of a nondescript concrete building in Cambridge, about a dozen Harvard University researchers spend their days trying to crack the code on something that's eluded scientists for decades.

"We're really lacking in our ability to accurately predict suicidal behavior and to prevent it," says psychology professor Matt Nock, who runs the so-called Nock Lab, which is focused entirely on suicide and self-harm. "We are really struggling with identifying which people who think about suicide go on to act on their suicidal thoughts and which ones don't."

Nock demonstrates a computer-based exercise he's using in his research, known as the Implicit Association Test, or IAT. The test asks patients to quickly classify words related to life or death — such as "thriving" or "suicide" — as being like them or like other people.

"For suicidal people, they're faster responding when 'death' and 'me' are paired on the same side of the screen. People who are non-suicidal are faster responding when 'death' and 'not me' are paired on the same side of the screen," Nock explains.

He and his team are evaluating the test by trying it out with patients in the psychiatric emergency room at Massachusetts General Hospital. The study participants do one other word classification exercise called Stroop and answer questions about addiction, mental illness and suicidal thoughts or behavior.

Nock is also collecting larger sets of data by offering the IAT and questionnaire to the public, through a website called Project Implicit Mental Health.

"And assuming [the tests] work well, our next question is, how do we give the information generated by these tasks to clinicians in a way that will be useful?" Nock says. "Do we give them a number? Do we give them a probability that a person is going to make a suicide attempt in the next week or month or several months? And that is not as simple as it sounds."

Research To Better Predict Imminent Suicide Risk

Suicide is the 10th-leading cause of death in the U.S., and more than 1 million people make suicide attempts each year. But research funding lags other causes of death. The National Institute of Mental Health says it spends $39 million per year funding suicide research.

Nock is the recipient of some of that funding. And he and his team recently received a $1 million grant from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) — the largest grant in AFSP's history. With the money, Nock and his team are combining data from their word association tests, people’s medical records and even apps the research participants are using to record real-time information about their suicidal thoughts or self-harming behaviors.

The study subjects also undergo blood work to identify genetic markers that may increase the risk of suicide. But Nock and other researchers point out that despite excitement and widespread reports about a suicide gene discovery last year, there is no single "suicide gene."

"There are genes that turn things on, genes that turn things off. And so it's a very complicated process," explains New York City-based clinical psychologist Jill Harkavy-Friedman.

Harkavy-Friedman says she hopes to some day have tools to better predict her clients' risk of suicide.

"We may not be able to control if they think about it, but we can help them control what they do about it," she says.

Harkavy-Friedman is the vice president of research for AFSP. She says with better diagnostic tools, she and other clinicians would be able to put emergency care plans in place for those at imminent risk and teach others how to divert their attention away from their suicidal thoughts.

"Then we can teach them alternate strategies for coping with those situations. And it does have an effect on the brain, because the brain is very dynamic," Harkavy-Friedman says.

That means certain therapies can actually alter how genes and biochemistry express themselves and affect health, she explains. Scientists are still trying to pinpoint how such changes in the brain might affect suicidal behavior, however.

'Suicide Is A Disease Of The Brain'

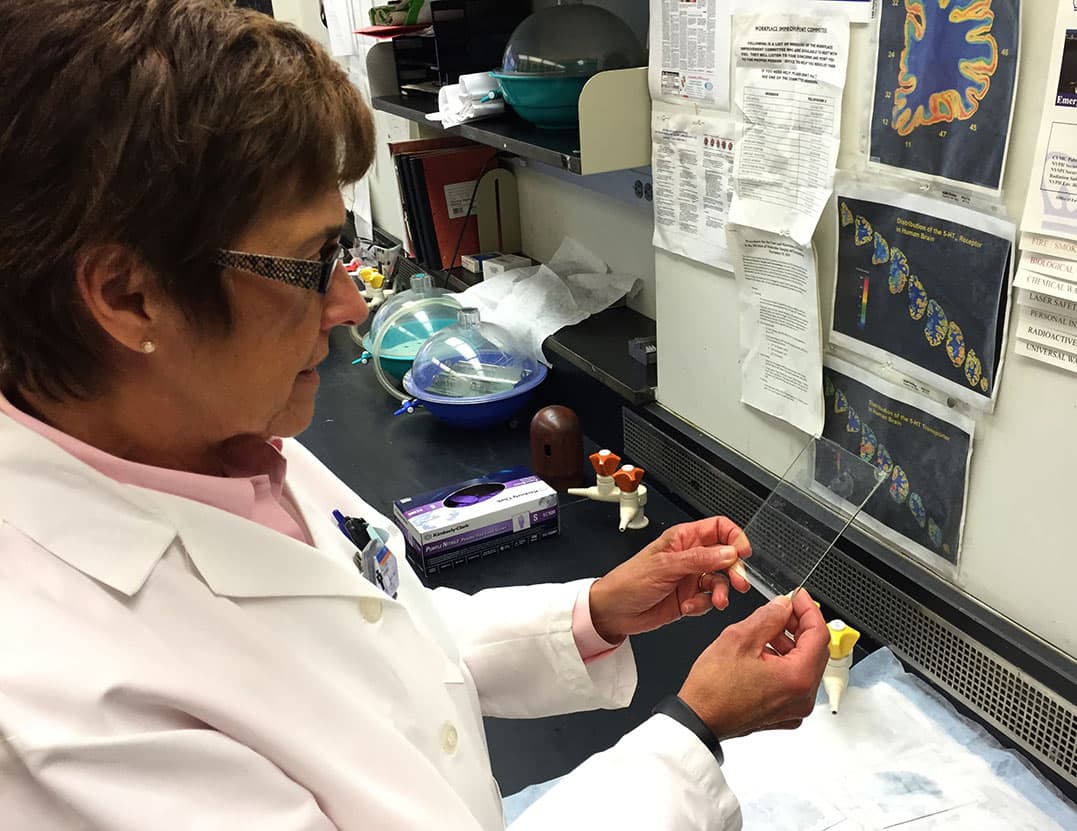

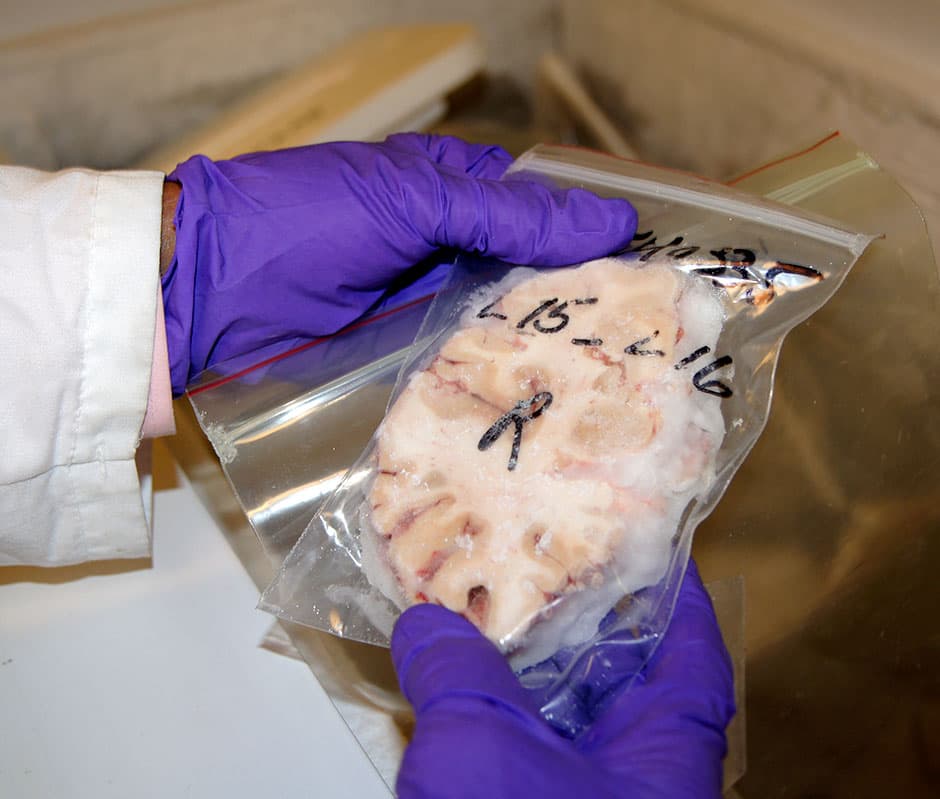

The incredible complexity of the brain has been driving Victoria Arango and other suicide researchers at Columbia University for decades. She's a neurobiologist and neuroanatomist who studies the brains of people who died by suicide and compares them with the brains of people who had depression but died from other causes, and those who didn't have mental illness.

In a lab in the New York State Psychiatric Institute, the Columbia researchers have collected 800 brains, which are stored in giant freezers. Under powerful microscopes, Arango and her colleagues can study the brains' details down to individual cells.

Arango says though the field of suicide research started late, as compared to other research, she's heartened by one major conclusion scientists have reached.

"That there is nothing like 'mental illness.' It's not an abstract thing. It has a place of residence and it's the brain, that suicide is a disease of the brain," Arango says.

She and Columbia psychiatrist John Mann made some of the earliest discoveries that led to that conclusion more than two decades ago, when they worked together at Cornell University and the University of Pittsburgh. They found that the neurotransmitter serotonin doesn't transmit as well in certain areas of the brain in those who die by suicide, as compared to other people.

They've since pinpointed the exact location of that abnormality in the brain, which they say is the key.

"When you look at the brain of a person who died by suicide, what you have is less serotonin going to a part of the brain that is involved with decision making or with controlling impulsivity," Arango explains.

That may be why some people view suicide as a way to quickly escape their pain, Mann says.

"The people who make suicide attempts do tend to have an immediate reward orientation in their decision making," Mann says. "The relief from the psychological pain of depression is worth more to them than the possibility of relief from treatment that's going to take weeks."

Mann says he and his colleagues are now finding similar abnormalities when they scan the brains of living people who are suicidal, and the degree of the brain abnormality is directly proportional to how lethal the person's suicidal behavior is. But researchers are still years away from possibly translating those findings into diagnostic tests doctors can routinely use.

'The Most Exciting Discovery'

In the shorter term, Mann sees promise in a medication that's producing stunning results and powerful reactions from patients in a clinical trial he and his Columbia colleagues are conducting.

"'Best I've ever felt. Haven't felt like this for years. I'm scared [the depression is] going to come back,' " Mann says, recalling comments from participants in the study.

The drug is ketamine, which doctors have long used as anesthesia in people and animals. Researchers at a handful of labs around the country, including Columbia, are studying it as a treatment for severe depression that doesn't respond to other meds. Mann says he thinks ketamine has the potential to save lives, as a suicide prevention treatment.

"In my view, this is the most exciting discovery in the treatment of major psychiatric disorders, particularly mood disorders, in the last 20 years," Mann says. "When it works, it works amazingly well. People don't get 20 percent better, 30 percent better. They get 60 percent, 70 percent, 80 percent better. And it works very fast. It works in a couple of hours."

Ketamine does have downsides. The drug, which is also used and abused recreationally under the street name "Special K," produces some psychotic side effects that disappear within a few hours in clinical trials. Right now, doctors can only administer the drug intravenously. But several pharmaceutical companies are conducting trials on oral and nasal spray versions of ketamine.

Studying Adolescent Suicide

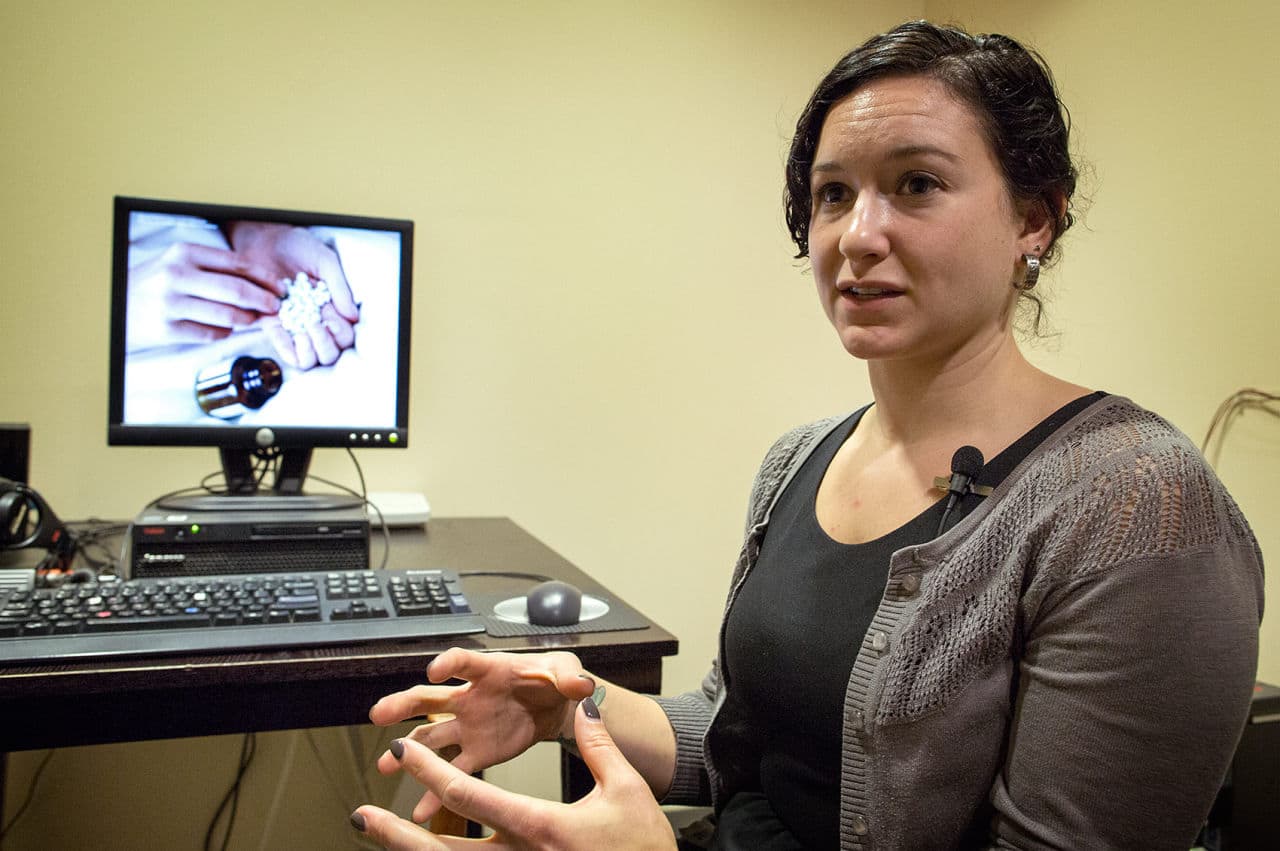

Back in the Nock Lab at Harvard, postdoctoral fellow Cassie Glenn is focused on suicidal behavior in adolescents. In her current study, she's testing how much a teen startles, by blinking, when hearing bursts of white noise at the same time images appear on a computer screen.

"So we put a couple of electrodes underneath the eye ... so we can measure the contraction when someone blinks," Glenn explains.

She demonstrates the test with another lab staffer acting as the mock research participant. The pictures popping up on the monitor range from neutral and mundane to pleasant images, like puppies and babies. They include frightening things, such as a snake, and images that imply someone might be about to take his or her life — standing on train tracks or looking down from a tall building, for example.

Glenn's early research has found teens who have attempted suicide startle less at the pictures related to suicidal behavior.

"What may separate them is that the individuals who go on to attempt [suicide] may have a reduced fear of death," Glenn says. "So it's not that they just have this desire to end their lives. But they actually may be less fearful of engaging in these kinds of behaviors."

Psychologists say experiences such as childhood trauma and drug abuse might contribute to someone being less fearful of self-harm or death -- just some of many factors that add to what researchers call a cocktail, or a storm, of influences that can come together to make someone suicidal.

For more on research priorities and immediate action steps some are calling for to reduce suicide, read Lynn Jolicoeur's conversation with the director of NIMH, Dr. Tom Insel.

Resources: You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) and the Samaritans Statewide Hotline at 1-877-870-HOPE (4673)