Advertisement

Why We Need To Talk Now About The Brave New World Of Editing Genes

Resume

It was standing room only in the Harvard Medical School auditorium last week, the atmosphere electric as an audience of hundreds hummed with anticipation — for a highly technical talk by a visiting scientist, Dr. Jennifer Doudna of Berkeley. Near the front sat the medical school's dean, Dr. Jeffrey Flier.

"I don’t believe in my years at Harvard Medical School I’ve ever seen a crowd of this magnitude for a lecture of this kind," he said.

The draw?

"The draw is, this is one of the most exciting topics in the scene of biology today."

That buzzworthy biology topic is a revolutionary new method to “edit” DNA that has spread to thousands of labs around the world just in the last couple of years.

Suddenly, it's no longer purely science fiction that humankind will have the ability to tinker with its own gene pool. But should it?

Learn This Acronym: CRISPR

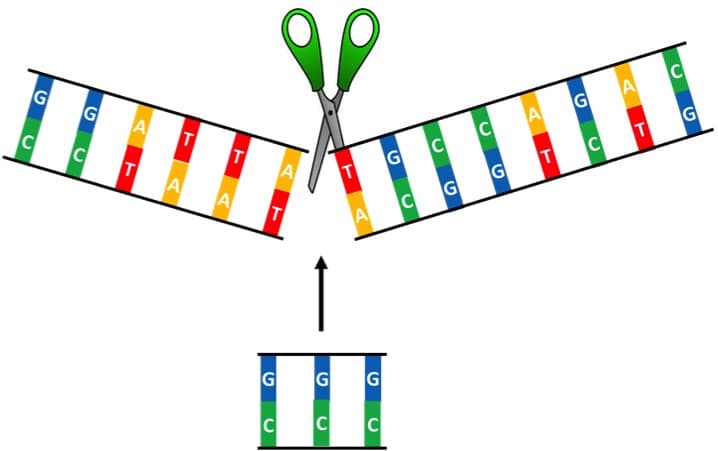

The hot new gene-editing tool is known by the acronym CRISPR, for “clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats.” It acts as a sort of molecular scissors that can be easily targeted to cut and modify specific genes.

CRISPR occurs naturally in bacteria, but scientists are now learning to harness its power to alter DNA for research across the board — cancer, HIV, brain disease — even to make better potatoes. Just this week, the journal Science published a paper on possibly using CRISPR to try to stop female mosquitoes from spreading deadly diseases.

CRISPR looks particularly promising for human diseases that hinge on just one gene, like sickle-cell anemia or cystic fibrosis. Someday, the hope is, CRISPR and gene-editing tools like it will let us cure what are now lifelong diseases by simply deleting and replacing a baby's "broken" gene.

"The name — definitely it’s a bit jargony, but it is actually an incredibly easy tool to use to manipulate DNA," says Katrine Bosley, the CEO of Editas Medicine, a Cambridge biotech company founded by leading CRISPR scientists to develop treatments for genetic diseases.

"Part of the reason there’s this incredible excitement in the scientific community," she says, "is that, as many people have picked it up and tried it, it’s worked for them. I’ve had scientists say to me, 'I tried it and my first experiment worked!' Now, that almost never happens. Not only does it almost never happen in science generally, it’s even rarer with a very new technology like this."

Back in the laboratory area of Editas Medicine, scientist Deepak Reyon uses CRISPR to make genetically modified cells and mice. These “models” are key for studying diseases and looking for possible cures — and they’re now far faster and easier to create.

"We can think about generating models at a rate of even two or three models in a week," he says. "We used to think about generating one mouse model in a year. Ten years ago, people would work on making one model for their PhD thesis."

Making People Nervous

So — sounds great, right? CRISPR is such a step forward that it’s been compared to going from a manual typewriter and White-Out to computerized word processing, with a lovely "Find" function that lets you search out and correct a given word. The buzz around CRISPR includes loud whispers of "Nobel prize," and a pending dispute over potentially very valuable patents.

But CRISPR is also making some people, including some scientists, very nervous. It’s raising the prospect of creating “designer babies” — manipulating genes to bolster intelligence, say, or immunity to disease — in ways that future generations will inherit. Remember "Brave New World"? Or the genetic "haves" and "have nots" in the movie "Gattaca"?

"The question is called," Bosley says, "when you have a technology that suggests something is possible as opposed to wholly theoretical."

Some argue that if and when we can make humanity better, especially by eradicating diseases, maybe we should.

The current reality, though, is that making designer babies is still very much science fiction. Chinese scientists reported in April that they had used CRISPR to edit the genes of human embryos that could never grow into babies anyway — but it didn’t work very well.

And CRISPR has a long way to go before any parent would ever want to use the technology on a baby, because it’s clearly not safe. It’s not specific enough to hit only the genes you’re targeting — it could change others as well. That's a challenge more immediately for making CRISPR-based therapies for patients with genetic diseases, which must be highly specific.

Dr. Keith Joung at Massachusetts General Hospital is working on that targeting problem.

"We now know that we can make a change at a desired target, a so-called on-target site," he says, "but what has been less clear is if we are causing changes elsewhere in the genome, at so-called off-target sites. So these would be unintended changes to the DNA."

To his knowledge, CRISPR-based therapies have not yet been tried in human clinical trials, he says.

But Let's Start Talking...

So CRISPR is still in its early days, but the discussion about using it to alter the human gene pool has already begun in the scientific community — mostly with calls not to cross the line into meddling with human heredity. Though some argue that if and when we can make humanity better — especially by eradicating diseases — maybe we should.

The National Academy of Sciences and other science leaders are planning an international summit for this fall to discuss "the scientific, ethical and policy issues" raised by gene-editing.

The first question, says Boston University bio-ethicist George Annas, is: "Should we ever use this technique on human embryos that are destined to become children? I actually think the answer to that is no." (Read a fuller discussion with Annas here: "A Taste of the Looming Ethical Debate On Gene-Editing Humans.")

He argues that the world needs to create a new global body to regulate changes to the human gene pool, maybe called something like The Human Species Protection Agency.

"We need new structures, new oversight, new transparency," he says. "The scientists can’t do it alone."

As the science of CRISPR keeps forging ahead, Annas and others are saying, we’d better start talking about where we want it to go — and how far.

Further reading: All CRISPR coverage by Antonio Regalado of Technology Review, particularly this vivid overview: "Engineering The Perfect Baby"

Further listening: On Point: Re-Engineering Human Embryos